- rsyslog

- Installation

- Starting service

- Configure hostname

- Configuration

- imjournal

- journald’s syslog-forward feature

- Facility levels

- Severity levels

- Examples

- journald with rsyslog for kernel messages

- Where to Find sshd Logs in Linux?

- Method 1: Using the “auth.log” File

- Method 2: Using the “lastlog” Command

- Method 3: Using the “journalctl” Command

- Conclusion

- Верните свои журналы в ArchLinux, как в Debian, или в другие дистрибутивы с помощью syslog-ng

rsyslog

rsyslog is a syslog implementation that offers many benefits over syslog-ng. It can be configured to receive log entries from systemd’s journal in order to process or filter them before quickly writing them to disk or sending them over network.

Installation

Note: It is recommended to disable and uninstall the syslog-ng package to prevent possible conflicts.

Starting service

You can start/enable rsyslog.service after installation.

Configure hostname

Rsyslog uses the glibc routine gethostname() or gethostbyname() to determine the hostname of the local machine. The gethostname() or gethostbyname() routine check the contents of /etc/hosts for the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) if you are not using BIND or NIS.

You can check what the local machine’s currently configured FQDN is by running hostname —fqdn . The output of hostname —short will be used by rsyslog when writing log messages. If you want to have full hostnames in logs, you need to add $PreserveFQDN on to the beginning of the file (before using any directive that write to files). This is because, rsyslog reads its configuration file and applies it on-the-go and then reads the later lines.

The /etc/hosts file contains a number of lines that map FQDNs to IP addresses and that map aliases to FQDNs. See the example /etc/hosts file below:

# # 127.0.0.1 localhost.localdomain somehost.localdomain localhost somehost ::1 localhost.localdomain somehost.localdomain localhost somehost

localhost.localdomain is the first item following the IP address, so gethostbyname() function will return localhost.localdomain as the local machine’s FQDN. Then /var/log/messages file will use localhost as hostname.

To use somehost as the hostname. Move somehost.localdomain to the first item:

# # 127.0.0.1 somehost.localdomain localhost.localdomain localhost somehost ::1 somehost.localdomain localhost.localdomain localhost somehost

Configuration

rsyslog is configured in /etc/rsyslog.conf . See the official documentation for more information on the available configuration options.

By default, all syslog messages are handled by systemd’s journal. In order to gather system logs in rsyslog, you either have to turn on #journald’s syslog-forward feature or use the #imjournal module of rsyslog to gather the logs by importing it from the systemd journald.

imjournal

If you want rsyslog to pull messages from systemd, load the imjournal module:

journald’s syslog-forward feature

The rsyslog AUR does not create its working directory /var/spool/rsyslog defined by the $WorkDirectory variable in the configuration file. You might need to create it manually or change its destination.

Log output can be fine tuned in /etc/rsyslog.conf . The daemon uses Facility levels (see below) to determine what gets put where. For example:

# The authpriv file has restricted access. authpriv.* /var/log/secure

States that all messages falling under the authpriv facility are logged to /var/log/secure .

Another example, which would be similar to the behaviour of syslog-ng for the old auth.log :

Facility levels

Note: The mapping between Facility Number and Keyword is not uniform over different operating systems and different syslog implementations. Use the keyword where possible, until it is determined which numbers are used by Arch.

| Facility Number | Keyword | Facility Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | kern | kernel messages |

| 1 | user | user-level messages |

| 2 | mail system | |

| 3 | daemon | system daemons |

| 4 | auth | security/authorization messages |

| 5 | syslog | messages generated internally by syslogd |

| 6 | lpr | line printer subsystem |

| 7 | news | network news subsystem |

| 8 | uucp | UUCP subsystem |

| 9 | clock daemon | |

| 10 | authpriv | security/authorization messages |

| 11 | ftp | FTP daemon |

| 12 | — | NTP subsystem |

| 13 | — | log audit |

| 14 | — | log alert |

| 15 | cron | clock daemon |

| 16 | local0 | local use 0 (local0) |

| 17 | local1 | local use 1 (local1) |

| 18 | local2 | local use 2 (local2) |

| 19 | local3 | local use 3 (local3) |

| 20 | local4 | local use 4 (local4) |

| 21 | local5 | local use 5 (local5) |

| 22 | local6 | local use 6 (local6) |

| 23 | local7 | local use 7 (local7) |

Severity levels

As defined in RFC 5424, there are eight severity levels:

| Code | Severity | Keyword | Description | General Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Emergency | emerg (panic) | System is unusable. | A «panic» condition usually affecting multiple apps/servers/sites. At this level it would usually notify all tech staff on call. |

| 1 | Alert | alert | Action must be taken immediately. | Should be corrected immediately, therefore notify staff who can fix the problem. An example would be the loss of a primary ISP connection. |

| 2 | Critical | crit | Critical conditions. | Should be corrected immediately, but indicates failure in a primary system, an example is a loss of a backup ISP connection. |

| 3 | Error | err (error) | Error conditions. | Non-urgent failures, these should be relayed to developers or admins; each item must be resolved within a given time. |

| 4 | Warning | warning (warn) | Warning conditions. | Warning messages, not an error, but indication that an error will occur if action is not taken, e.g. file system 85% full — each item must be resolved within a given time. |

| 5 | Notice | notice | Normal but significant condition. | Events that are unusual but not error conditions — might be summarized in an email to developers or admins to spot potential problems — no immediate action required. |

| 6 | Informational | info | Informational messages. | Normal operational messages — may be harvested for reporting, measuring throughput, etc. — no action required. |

| 7 | Debug | debug | Debug-level messages. | Info useful to developers for debugging the application, not useful during operations. |

Tip: A common mnemonic used to remember the syslog levels in reverse order: «Do I Notice When Evenings Come Around Early».

Examples

journald with rsyslog for kernel messages

This article or section needs language, wiki syntax or style improvements. See Help:Style for reference.

Since the syslog component of systemd, journald, does not flush its logs to disk during normal operation, these logs will be gone when the machine is shut down abnormally (power loss, kernel lock-ups, . ). In the case of kernel lock-ups, it can be important to have some kernel logs for debugging. Until journald gains a configuration option for flushing kernel logs, rsyslog can be used in conjunction with journald.

- journald must still get all log messages.

- rsyslog must only log kernel messages, all other logs are handled by journald.

- Kernel logs must be logged separatedly to /var/log/kernel.log .

- Use systemd to start the service.

Installation and configuration steps:

- Install rsyslogAUR .

- Edit /etc/logrotate.d/rsyslog and add /var/log/kernel.log to the list of logs. Without this modification, the kernel log would grow indefinitely.

- Edit /etc/rsyslog.conf and comment everything except for $ModLoad imklog . If a heart-beat (repeated confirmation that the log is alive) is preferred, $ModLoad immark should remain uncommented as well.

- Add the next line to the same configuration file:

kern.* /var/log/kernel.log;RSYSLOG_TraditionalFileFormat

$ sed 's/^Sockets=/#&/' /usr/lib/systemd/system/rsyslog.service | sudo tee /etc/systemd/system/rsyslog.service

Note: rsyslog reads from /proc/kmsg . This means that subsequent reads from that file (either the user or a syslog daemon) will not read «old» logs from that file anymore. journald is not affected as it reads from /dev/kmsg which allows multiple readers.

Where to Find sshd Logs in Linux?

The “sshd” is an abbreviation of the “Secure Shell Daemon” of an OpenSSH server. It manages incoming connections utilizing the SSH protocol as a server. It also allows the user to access the details like encryption, file transfers, terminal connections, tunneling, and user authentication. The “sshd-logs” handles the user authentication details, i.e., authorized/unauthorized login attempts.

This post illustrates the sshd logs’ exact location and how the user can check them in Ubuntu.

Method 1: Using the “auth.log” File

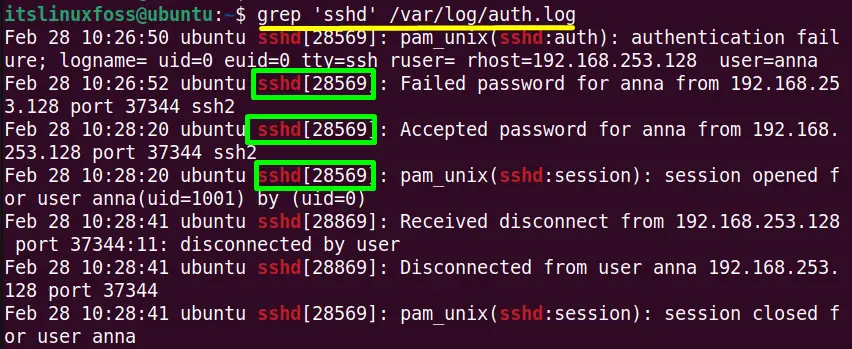

The “sshd logs” are in the “auth.log” file which is located in the “/var/log/” directory. It stores the authorization attempts details of the system like user logins, used authorized mechanism, and sshd logs.

Run the “grep” to filter out the “sshd logs” details from the “/var/log/auth.log” file:

$ grep ‘sshd’ /var/log/secure #For Fedora/CentOS/RHEL $ grep ‘sshd’ /var/log/auth.log #For Ubuntu/Debian-Based

The output shows all the “sshd” sessions details such as date, hostname, logname, port no and many others with the process ID “28569”.

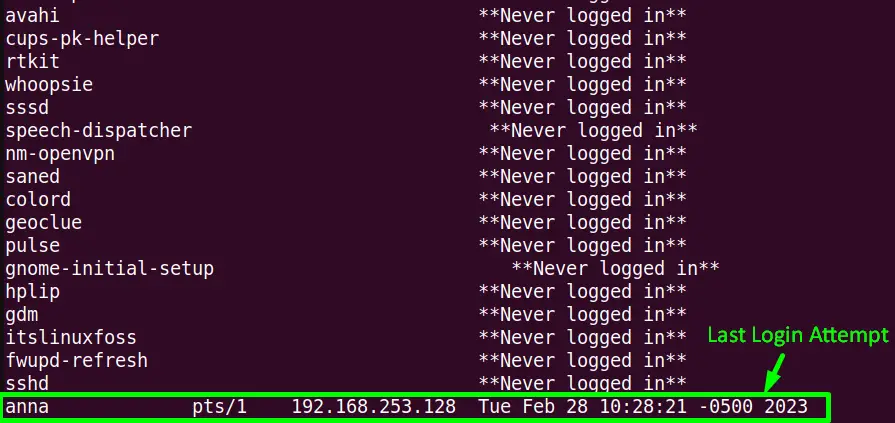

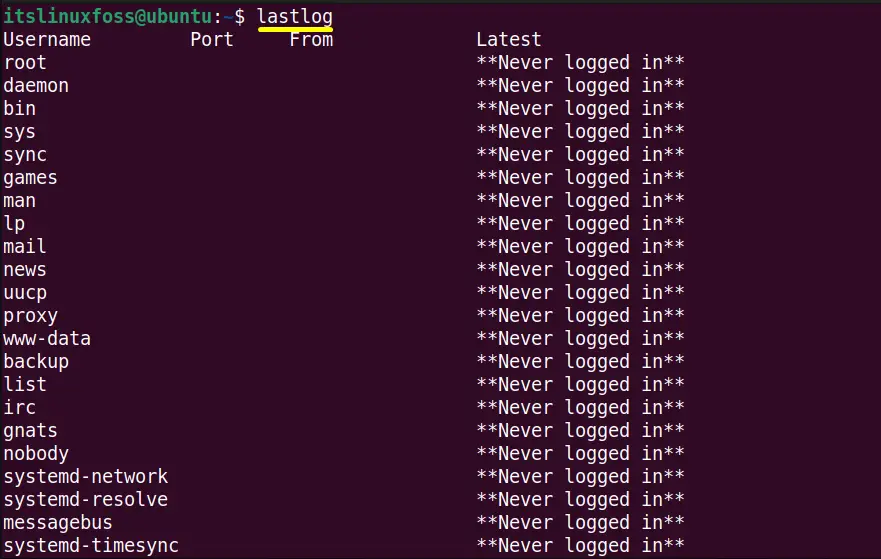

Method 2: Using the “lastlog” Command

The “lastlog” command line utility is a program that displays the last login attempts details of the system accounts. The login details include port, login name, last login, and also the sshd logs.

Execute the “lastlog” command without any of its supported flags to list down the “sshd logs” details:

All the login attempts information has been displayed on the terminal.

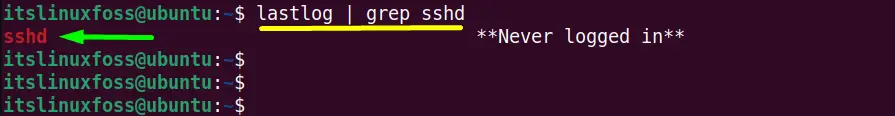

To filter out only the “sshd logs” details, use the combination of “lastlog” and “grep” commands with the “|(Pipe)” character in this way:

The “sshd logs” contains no logged-in attempts.

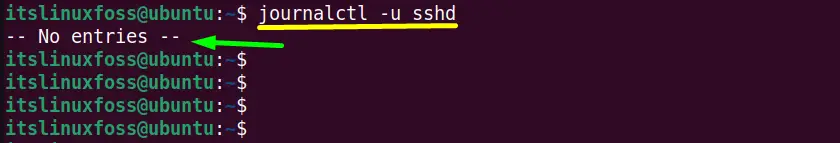

Method 3: Using the “journalctl” Command

The “journalctl” is another command line tool that provides the log (including sshd logs) details of the systemd journaling system. It provides the systemd logs collection and systemd services and gets the messages from the kernel.

Use the “journalctl” command followed by the “-u(specifies unit “systemd”)” flag to show the “sshd logs” in the terminal:

The “sshd logs” contains “No entries” same as the “lastlog” output.

Conclusion

In Linux, the “sshd logs” are stored in the “/var/log/auth.log” file. These log details can be displayed using the “grep”, “lastlog”, and the “journalctl” command line utilities. All these utilities are pre-installed in the commonly used Linux distribution like “Fedora”, “CentOS”, “RHEL”, “Ubuntu/Debian”, and many others.

This post has listed down the sshd logs’ exact location and all possible methods to view them.

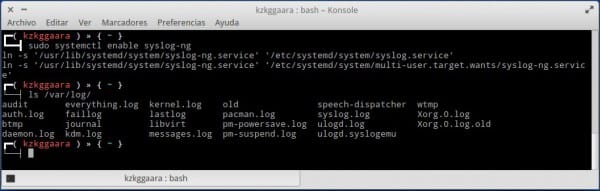

Верните свои журналы в ArchLinux, как в Debian, или в другие дистрибутивы с помощью syslog-ng

Хотя в ArchLinux у нас есть Systemd, С systemctl Мы можем видеть системные журналы, некоторые из нас все еще пропускают журналы типа /var/log/auth.log или аналогичные, которые по умолчанию в ArchLinux мы не можем найти. Почему? . просто потому, что мы уже адаптированы к их использованию, потому что в других дистрибутивах, таких как Debian, Ubuntu и т. д., они бывают такими, как при жизни.

Возьмем, к примеру, auth.log, который должен находиться в / var / log / (по умолчанию это не так). Если в ArchLinux мы хотим, чтобы этот журнал возвращался туда, где он всегда был, чтобы знать попытки аутентификации на нашем и других компьютерах, чтобы иметь уверенность в безопасности за пределами брандмауэра, syslog-ng может быть отличной альтернативой.

Сначала мы должны установить его в ArchLinux:

После установки приступаем к его запуску:

sudo systemctl start syslog-ng

Затем, чтобы он запустился автоматически, мы включаем его с помощью enable:

sudo systemctl enable syslog-ng

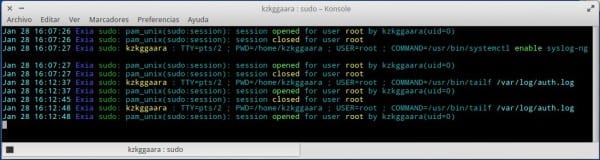

Как видите, у нас уже есть файлы журналов, которых у нас не было раньше, например auth.log, связанный с аутентификацией, с помощью которых (и вдаваясь в подробности) мы можем узнать попытки (не удалось или разрешено) входа через SSH, внутренние логины как таковые и т. д. Давай, с ним это как бревно нашего дома срочно слесарь 24ч 7 дней в неделю 😀

Кстати, если вы спросите, как я раскрашивал журналы, я это делал ccze.

На этом пост заканчивается. Это больше, чем что-либо другое, для меня меморандум, но я надеюсь, что он будет полезен не одному 🙂

Содержание статьи соответствует нашим принципам редакционная этика. Чтобы сообщить об ошибке, нажмите здесь.

Полный путь к статье: Из Linux » Учебники / Руководства / Советы » Верните свои журналы в ArchLinux, как в Debian, или в другие дистрибутивы с помощью syslog-ng