Linux Jargon Buster: What is a Package Manager in Linux? How Does it Work?

Learn about packaging system and package managers in Linux. You’ll learn how do they work and what kind of package managers available.

One of the main points how Linux distributions differ from each other is the package management. In this part of the Linux jargon buster series, you’ll learn about packaging and package managers in Linux. You’ll learn what are packages, what are package managers and how do they work and what kind of package managers available.

What is a package manager in Linux?

In simpler words, a package manager is a tool that allows users to install, remove, upgrade, configure and manage software packages on an operating system. The package manager can be a graphical application like a software center or a command line tool like apt-get or pacman. You’ll often find me using the term ‘package’ in tutorials and articles on It’s FOSS. To understand package manager, you must understand what a package is.

What is a package?

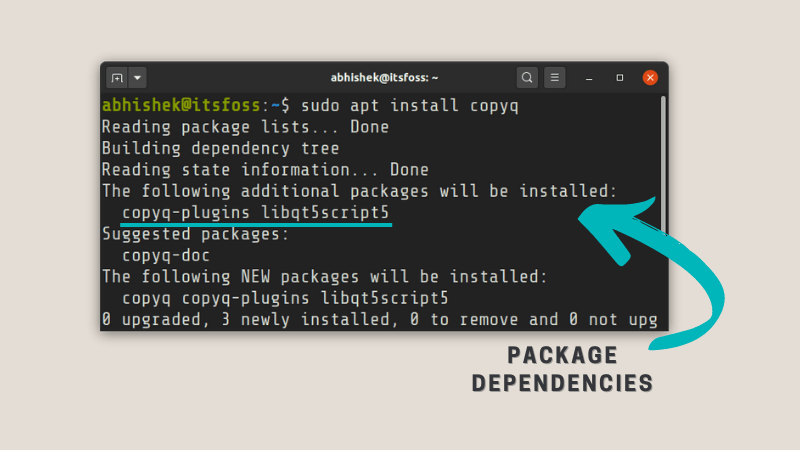

A package is usually referred to an application but it could be a GUI application, command line tool or a software library (required by other software programs). A package is essentially an archive file containing the binary executable, configuration file and sometimes information about the dependencies. In older days, software used to installed from its source code. You would refer to a file (usually named readme) and see what software components it needs, location of binaries. A configure script or makefile is often included. You will have to compile the software or on your own along with handling all the dependencies (some software require installation of other software) on your own. To get rid of this complexity, Linux distributions created their own packaging format to provide the end users ready-to-use binary files (precompiled software) for installing software along with some metadata (version number, description) and dependencies. It is like baking a cake versus buying a cake. Around mid 90s, Debian created .deb or DEB packaging format and Red Hat Linux created .rpm or RPM (short for Red Hat Package Manager) packaging system. Compiling source code still exists but it is optional now. To interact with or use the packaging systems, you need a package manager.

How does the package manager work?

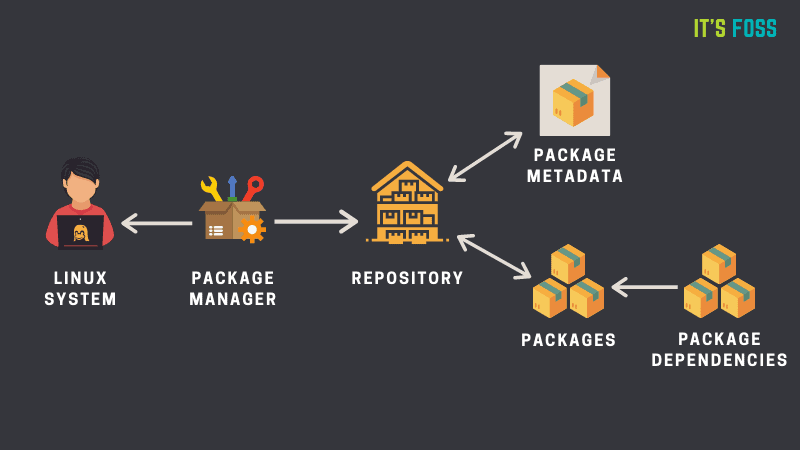

Please keep in mind that package manager is a generic concept and it’s not exclusive to Linux. You’ll often find package manager for different software or programming languages. There is PIP package manager just for Python packages. Even Atom editor has its own package manager. Since the focus in this article is on Linux, I’ll take things from Linux’s perspective. However, most of the explanation here could be applied to package manager in general as well. I have created this diagram (based on SUSE Wiki) so that you can easily understand how a package manager works.

Different kinds of package managers

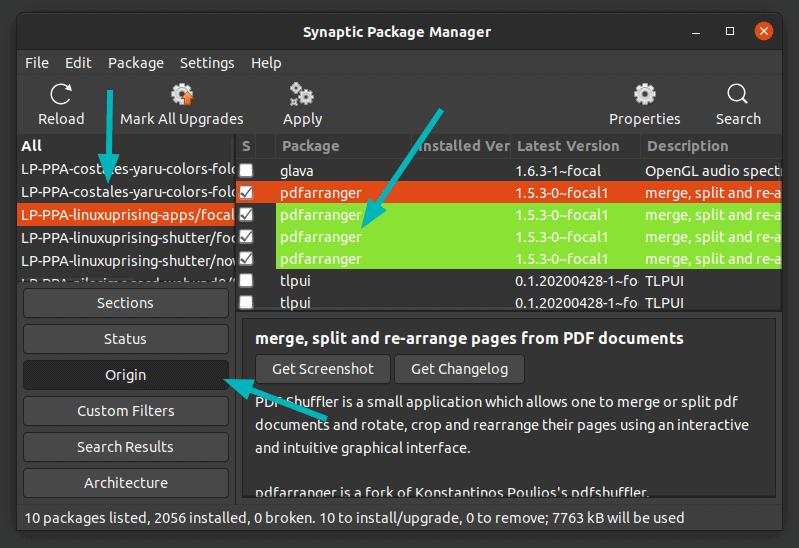

Package Managers differ based on packaging system but same packaging system may have more than one package manager. For example, RPM has Yum and DNF package managers. For DEB, you have apt-get, aptitude command line based package managers. Package managers are not necessarily command line based. You have graphical package managing tools like Synaptic. Your distribution’s software center is also a package manager even if it runs apt-get or DNF underneath.

Conclusion

I don’t want to go in further detail on this topic because I can go on and on. But it will deviate from the objective of the topic which is to give you a basic understanding of package manager in Linux. I have omitted the new universal packaging formats like Snap and Flatpak for now. I do hope that you have a bit better understanding of the package management system in Linux. If you are still confused or if you have some questions on this topic, please use the comment system. I’ll try to answer your questions and if required, update this article with new points.