- A beginner’s guide to navigating the Linux filesystem

- The basics

- Great Linux resources

- Print working directory ( pwd )

- Change directory ( cd )

- Wrapping up

- 7 Ways to Determine the File System Type in Linux (Ext2, Ext3 or Ext4)

- 1. Using df Command

- 2. Using fsck Command

- 3. Using lsblk Command

- 4. Using mount Command

- 5. Using blkid Command

- 6. Using file Command

- 7. Using fstab File

- Related Posts

- 15 thoughts on “7 Ways to Determine the File System Type in Linux (Ext2, Ext3 or Ext4)”

A beginner’s guide to navigating the Linux filesystem

As a new Linux user, one of the first skills that you need to master is navigating the Linux filesystem. These basic navigation commands will get you up to speed.

The basics

Great Linux resources

Before we get into commands, let’s talk about important special characters. The dot ( . ) , dot-dot ( .. ) , forward slash ( / ), and tilde ( ~ ), all have special functionality in the Linux filesystem:

- The dot ( . ) represents the current directory in the filesystem.

- The dot-dot ( .. ) represents one level above the current directory.

- The forward slash ( / ) represents the «root» of the filesystem. (Every directory/file in the Linux filesystem is nested under the root / directory.)

- The tilde ( ~ ) represents the home directory of the currently logged in user.

I believe that the best way to understand any concept is by putting it into practice. This navigation command overview will help you to better understand how all of this works.

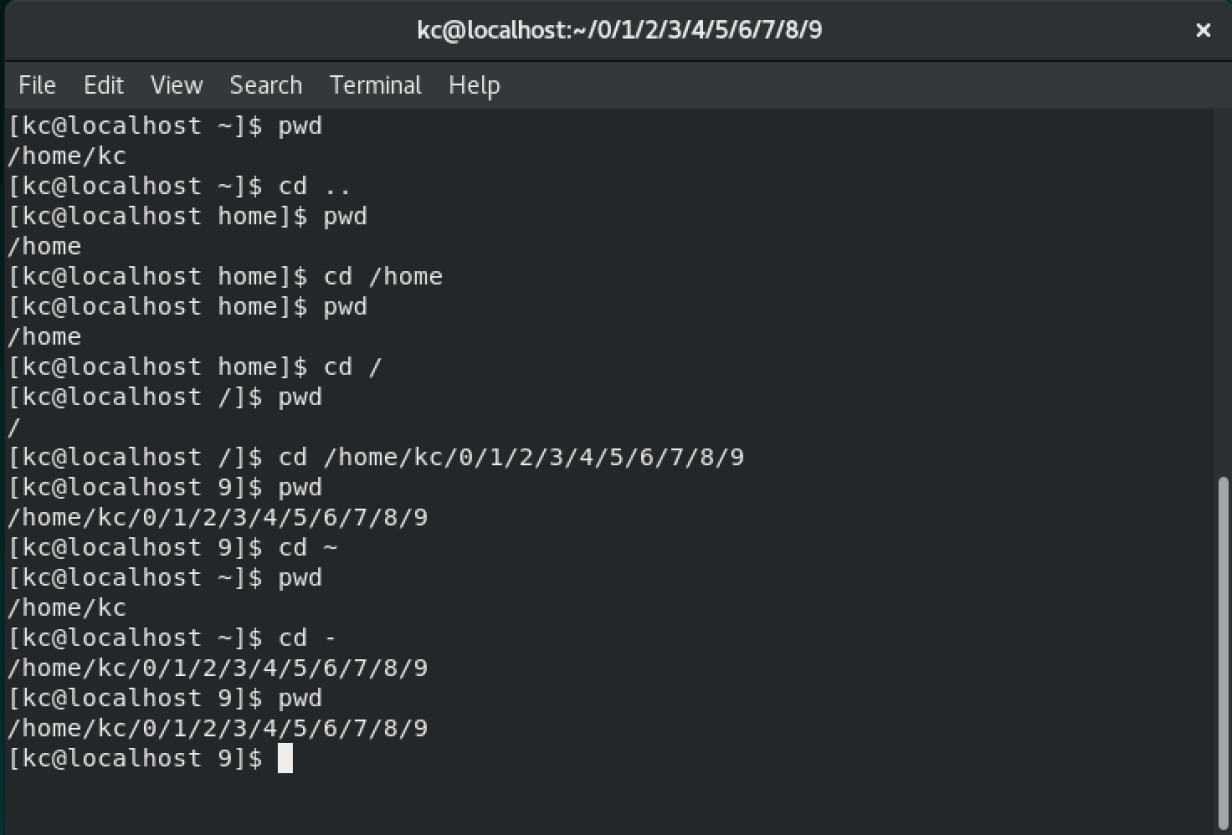

Print working directory ( pwd )

The pwd command prints the current/working directory, telling where you are currently located in the filesystem. This command comes to your rescue when you get lost in the filesystem, and always prints out the absolute path.

What is an absolute path? An absolute path is the full path to a file or directory. It is relative to the root directory ( / ). Note that it is a best practice to use absolute paths when you use file paths inside of scripts. For example, the absolute path to the ls command is: /usr/bin/ls .

If it’s not absolute, then it’s a relative path. The relative path is relative to your present working directory. If you are in your home directory, for example, the ls command’s relative path is: . ./../usr/bin/ls .

Change directory ( cd )

The cd command lets you change to a different directory. When you log into a Linux machine or fire up a terminal emulator, by default your working directory is your home directory. My home directory is /home/kc . In your case, it is probably /home/ .

Absolute and relative paths make more sense when we look at examples for the cd command. If you need to move one level up from your working directory, in this case /home , we can do this couple of ways. One way is to issue a cd command relative to your pwd :

Note: Remember, .. represents the directory one level above the working directory.

The other way is to provide the absolute path to the directory:

Either way, we are now inside /home . You can verify this by issuing pwd command. Then, you can move to the filesystem’s root ( / ) by issuing this command:

If your working directory is deeply nested inside the filesystem and you need to return to your home directory, this is where the ~ comes in with the cd command. Let’s put this into action and see how cool this command can be. It helps you save a ton of time while navigating in the filesystem.

My present working directory is root ( / ). If you’re following along, yours should be same, or you can find out yours by issuing pwd . Let’s cd to another directory:

$ cd /home/kc/0/1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9 $ pwd /home/kc/0/1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9 To navigate back to your home directory, simply issue ~ with the cd command:

Again, check your present working directory with the pwd command:

The dash ( — ) navigates back to the previous working directory, similar to how you can navigate to your user home directory with ~ . If you need to go back to our deeply nested directory 9 under your user home directory (this was my previous working directory), you would issue this command:

Wrapping up

These commands are your navigation tools inside the Linux filesystem. With what you learned here, you can always find your way to the home (~) directory. If you want to learn more and master the command line, check out 10 basic Linux commands.

Want to try out Red Hat Enterprise Linux? Download it now for free.

7 Ways to Determine the File System Type in Linux (Ext2, Ext3 or Ext4)

A file system is the way in which files are named, stored, retrieved as well as updated on a storage disk or partition; the way files are organized on the disk.

A file system is divided in two segments called: User Data and Metadata (file name, time it was created, modified time, it’s size and location in the directory hierarchy etc).

In this guide, we will explain seven ways to identify your Linux file system type such as Ext2, Ext3, Ext4, BtrFS, GlusterFS plus many more.

1. Using df Command

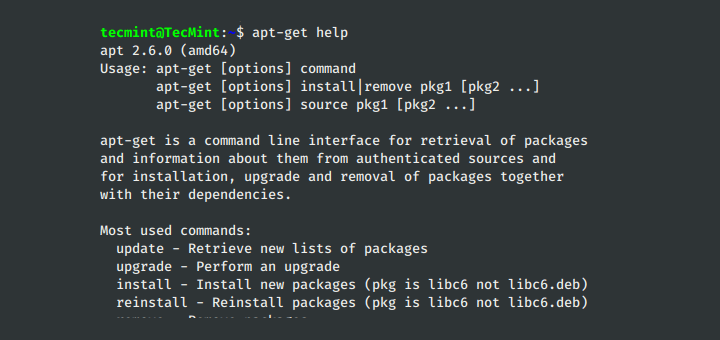

df command reports file system disk space usage, to include the file system type on a particular disk partition, use the -T flag as below:

$ df -Th OR $ df -Th | grep "^/dev"

For a comprehensive guide for df command usage go through our articles:

2. Using fsck Command

fsck is used to check and optionally repair Linux file systems, it can also print the file system type on specified disk partitions.

The flag -N disables checking of file system for errors, it just shows what would be done (but all we need is the file system type):

$ fsck -N /dev/sda3 $ fsck -N /dev/sdb1

3. Using lsblk Command

lsblk displays block devices, when used with the -f option, it prints file system type on partitions as well:

4. Using mount Command

mount command is used to mount a file system in Linux, it can also be used to mount an ISO image, mount remote Linux filesystem and so much more.

When run without any arguments, it prints info about disk partitions including the file system type as below:

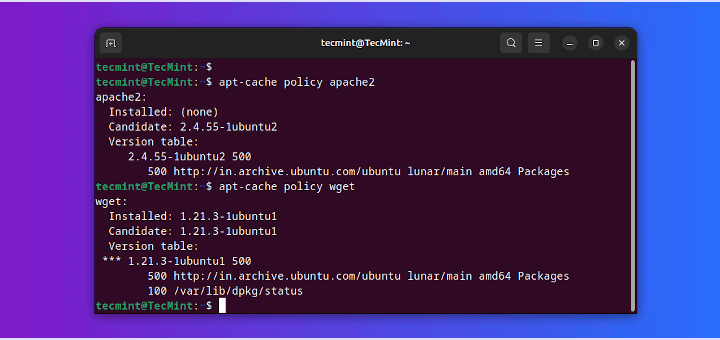

5. Using blkid Command

blkid command is used to find or print block device properties, simply specify the disk partition as an argument like so:

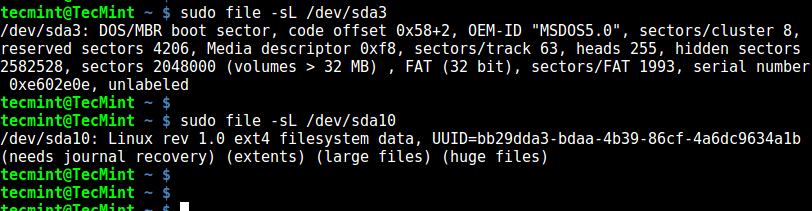

6. Using file Command

file command identifies file type, the -s flag enables reading of block or character files and -L enables following of symlinks:

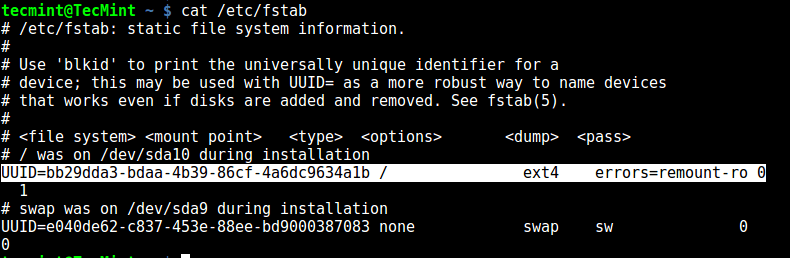

7. Using fstab File

The /etc/fstab is a static file system info (such as mount point, file system type, mount options etc) file:

That’s it! In this guide, we explained seven ways to identify your Linux file system type. Do you know of any method not mentioned here? Share it with us in the comments.

Aaron Kili is a Linux and F.O.S.S enthusiast, an upcoming Linux SysAdmin, web developer, and currently a content creator for TecMint who loves working with computers and strongly believes in sharing knowledge.

Each tutorial at TecMint is created by a team of experienced Linux system administrators so that it meets our high-quality standards.

Related Posts

15 thoughts on “7 Ways to Determine the File System Type in Linux (Ext2, Ext3 or Ext4)”

will create a ext2 filesystem on image1, if its not big enough (warning “Filesystem too small for a journal” means a filesystem without a journal, a.k.a. ext2, is created) If you don’t realize this and nevertheless mount it as ext4. The df and mount methods above will mirror back ext4:

$ df -Th /tmp/mnt* Filesystem Type Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on /dev/loop4 ext4 1003K 24K 908K 3% /tmp/mnt1 /dev/loop5 ext4 987K 33K 812K 4% /tmp/mnt2 $ mount | grep mnt . /home/mallikab/image1 on /tmp/mnt1 type ext4 (rw,relatime,seclabel) /home/mallikab/image2 on /tmp/mnt2 type ext4 (rw,relatime,seclabel,data=ordered)

$ fsck -N /tmp/mnt1 fsck from util-linux 2.23.2 [/sbin/fsck.ext2 (1) -- /tmp/mnt1] fsck.ext2 /tmp/mnt1 $ fsck -N /tmp/mnt2 fsck from util-linux 2.23.2 [/sbin/fsck.ext4 (1) -- /tmp/mnt2] fsck.ext4 /home/mallikab/image2 $ file -sL /home/mallikab/image2 /home/mallikab/image2: Linux rev 1.0 ext4 filesystem data, UUID=b4e8e086-54ca-4d9d-9f38-32bbed211e6b (needs journal recovery) (extents) (64bit) (huge files) $ file -sL /home/mallikab/image1 /home/mallikab/image1: Linux rev 1.0 ext2 filesystem data (mounted or unclean), UUID=09b3a8c9-0b6d-43c5-b195-c45f6c091765 (extents) (64bit) (huge files) hm, although fsck doesn't indicate ext2 unless the images are mounted, i.e. $ fsck -N ~/image1 fsck from util-linux 2.23.2 [/sbin/fsck.ext4 (1) -- /home/mallikab/image1] fsck.ext4 /home/mallikab/image1

The only working method for me was ‘ lsblk -f ‘; the other replied “fuseblk“, “HPFS/NTFS/exFAT” or nothing. Reply