Functions in bash linux

Shell functions are a way to group commands for later execution using a single name for the group. They are executed just like a «regular» command. When the name of a shell function is used as a simple command name, the list of commands associated with that function name is executed. Shell functions are executed in the current shell context; no new process is created to interpret them.

Functions are declared using this syntax:

fname () compound-command [ redirections ]

function fname [()] compound-command [ redirections ]

This defines a shell function named fname . The reserved word function is optional. If the function reserved word is supplied, the parentheses are optional. The body of the function is the compound command compound-command (see Compound Commands). That command is usually a list enclosed between < and >, but may be any compound command listed above. If the function reserved word is used, but the parentheses are not supplied, the braces are recommended. compound-command is executed whenever fname is specified as the name of a simple command. When the shell is in POSIX mode (see Bash POSIX Mode), fname must be a valid shell name and may not be the same as one of the special builtins (see Special Builtins). In default mode, a function name can be any unquoted shell word that does not contain ‘ $ ’. Any redirections (see Redirections) associated with the shell function are performed when the function is executed. A function definition may be deleted using the -f option to the unset builtin (see Bourne Shell Builtins).

The exit status of a function definition is zero unless a syntax error occurs or a readonly function with the same name already exists. When executed, the exit status of a function is the exit status of the last command executed in the body.

Note that for historical reasons, in the most common usage the curly braces that surround the body of the function must be separated from the body by blank s or newlines. This is because the braces are reserved words and are only recognized as such when they are separated from the command list by whitespace or another shell metacharacter. Also, when using the braces, the list must be terminated by a semicolon, a ‘ & ’, or a newline.

When a function is executed, the arguments to the function become the positional parameters during its execution (see Positional Parameters). The special parameter ‘ # ’ that expands to the number of positional parameters is updated to reflect the change. Special parameter 0 is unchanged. The first element of the FUNCNAME variable is set to the name of the function while the function is executing.

All other aspects of the shell execution environment are identical between a function and its caller with these exceptions: the DEBUG and RETURN traps are not inherited unless the function has been given the trace attribute using the declare builtin or the -o functrace option has been enabled with the set builtin, (in which case all functions inherit the DEBUG and RETURN traps), and the ERR trap is not inherited unless the -o errtrace shell option has been enabled. See Bourne Shell Builtins, for the description of the trap builtin.

The FUNCNEST variable, if set to a numeric value greater than 0, defines a maximum function nesting level. Function invocations that exceed the limit cause the entire command to abort.

If the builtin command return is executed in a function, the function completes and execution resumes with the next command after the function call. Any command associated with the RETURN trap is executed before execution resumes. When a function completes, the values of the positional parameters and the special parameter ‘ # ’ are restored to the values they had prior to the function’s execution. If a numeric argument is given to return , that is the function’s return status; otherwise the function’s return status is the exit status of the last command executed before the return .

Variables local to the function may be declared with the local builtin (local variables). Ordinarily, variables and their values are shared between a function and its caller. These variables are visible only to the function and the commands it invokes. This is particularly important when a shell function calls other functions.

In the following description, the current scope is a currently- executing function. Previous scopes consist of that function’s caller and so on, back to the «global» scope, where the shell is not executing any shell function. Consequently, a local variable at the current local scope is a variable declared using the local or declare builtins in the function that is currently executing.

Local variables «shadow» variables with the same name declared at previous scopes. For instance, a local variable declared in a function hides a global variable of the same name: references and assignments refer to the local variable, leaving the global variable unmodified. When the function returns, the global variable is once again visible.

The shell uses dynamic scoping to control a variable’s visibility within functions. With dynamic scoping, visible variables and their values are a result of the sequence of function calls that caused execution to reach the current function. The value of a variable that a function sees depends on its value within its caller, if any, whether that caller is the «global» scope or another shell function. This is also the value that a local variable declaration «shadows», and the value that is restored when the function returns.

For example, if a variable var is declared as local in function func1 , and func1 calls another function func2 , references to var made from within func2 will resolve to the local variable var from func1 , shadowing any global variable named var .

The following script demonstrates this behavior. When executed, the script displays

In func2, var = func1 local

func1() < local var='func1 local' func2 >func2() < echo "In func2, var = $var" >var=global func1

The unset builtin also acts using the same dynamic scope: if a variable is local to the current scope, unset will unset it; otherwise the unset will refer to the variable found in any calling scope as described above. If a variable at the current local scope is unset, it will remain so (appearing as unset) until it is reset in that scope or until the function returns. Once the function returns, any instance of the variable at a previous scope will become visible. If the unset acts on a variable at a previous scope, any instance of a variable with that name that had been shadowed will become visible (see below how localvar_unset shell option changes this behavior).

Function names and definitions may be listed with the -f option to the declare ( typeset ) builtin command (see Bash Builtin Commands). The -F option to declare or typeset will list the function names only (and optionally the source file and line number, if the extdebug shell option is enabled). Functions may be exported so that child shell processes (those created when executing a separate shell invocation) automatically have them defined with the -f option to the export builtin (see Bourne Shell Builtins).

Functions may be recursive. The FUNCNEST variable may be used to limit the depth of the function call stack and restrict the number of function invocations. By default, no limit is placed on the number of recursive calls.

Функции bash в скриптах

Наверное, всем известно, что у оболочки Bash есть встроенные команды, которых нет в папках /bin или /usr/bin. Они встроены в оболочку и выполняются в виде функций. В одной из предыдущих статей мы рассматривали написание скриптов на Bash. Мы обговорили там почти все, как должны выглядеть скрипты, использование условий, циклов, переменных, но не останавливались на функциях.

В сегодняшней статье мы исправим этот недостаток. Как и в любом языке программирования, в Bash есть функции их может быть очень полезно использовать. Мы рассмотрим использование функций bash, как их писать и даже как создавать библиотеки из этих функций.

Написание функций Bash

Сначала нужно понять что такое функция в нашем контексте. Функция — это набор команд, объединенных одним именем, которые выполняют определенную задачу. Функция вызывается по ее имени, может принимать параметры и возвращать результат работы. Одним словом, функции Bash работают так же, как и в других языках программирования.

Синтаксис создания функции очень прост:

Имя функции не должно совпадать ни с одной из существующих команд или функций, а все команды в теле функции пишутся с новой строки.

Простая функция

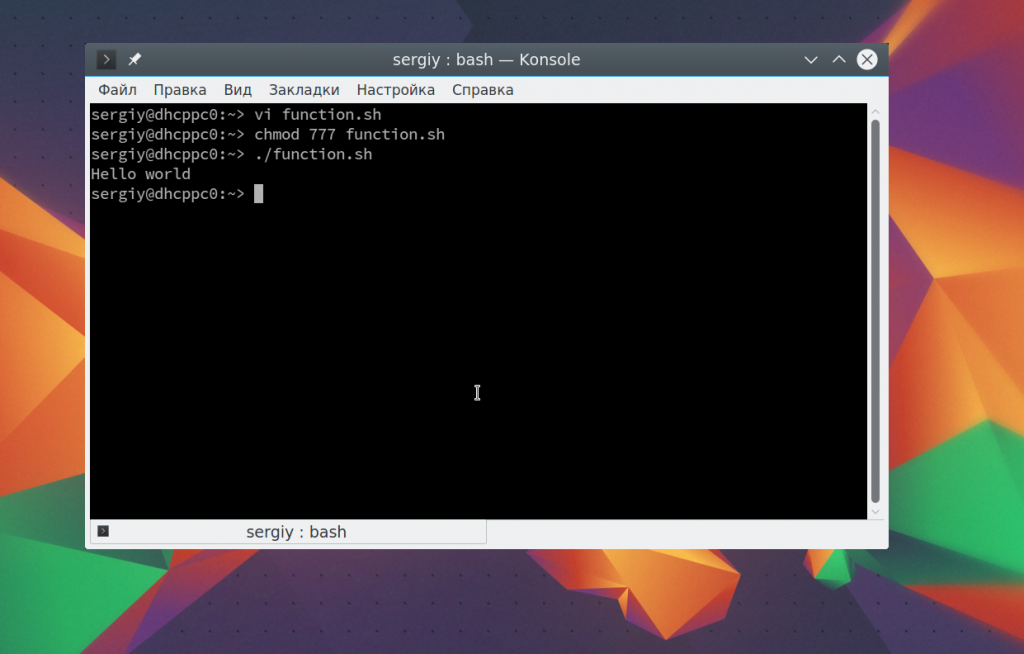

Давайте напишем небольшую функцию, которая будет выводить строку на экран:

#!/bin/bash

printstr() echo «hello world»

>

printstr

Вызов функции bash выполняется указанием ее имени, как для любой другой команды. Запустите наш скрипт на выполнение, не забывайте, что перед этим нужно дать ему права на выполнение:

Все работает, теперь усложним задачу, попробуем передать функции аргументы.

Аргументы функции

Аргументы функции нужно передавать при вызове, а читаются они точно так же, как и аргументы скрипта. Синтаксис вызова функции с параметрами bash такой:

имя_функции аргумент1 аргумент2 . аргументN

Как видите, все достаточно просто. Параметры разделяются пробелом. Теперь улучшим нашу функцию, чтобы она выводила заданную нами строку:

!/bin/bash

printstr() echo $1

>

printstr «Hello world»

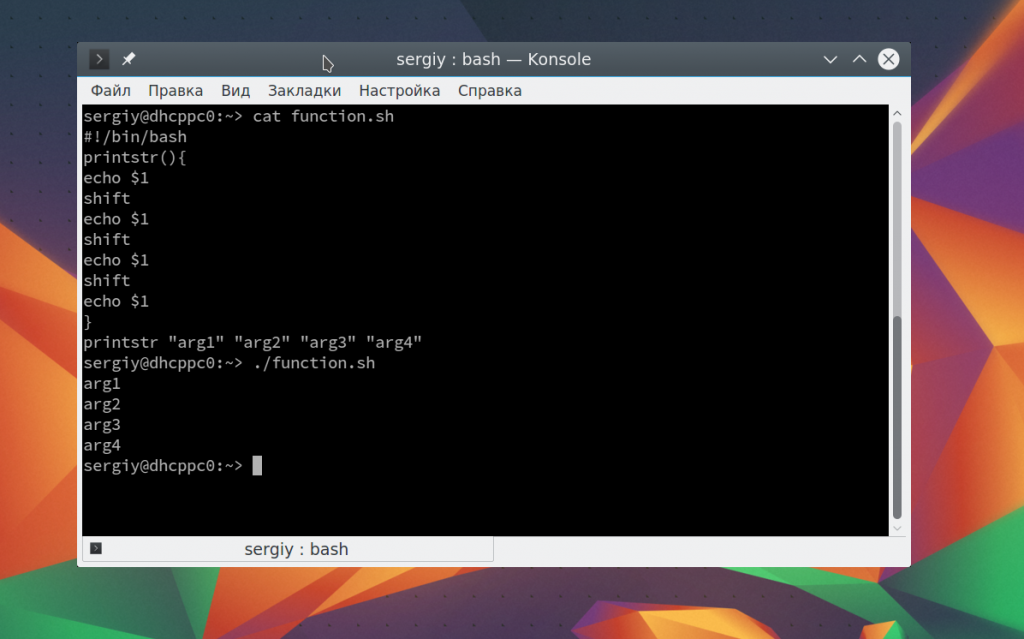

Можно сделать, чтобы параметров было несколько:

!/bin/bash

printstr() echo $1

echo $2

echo $3

echo $5

>

printstr «arg1» «arg2» «arg3» «arg4» «arg5»

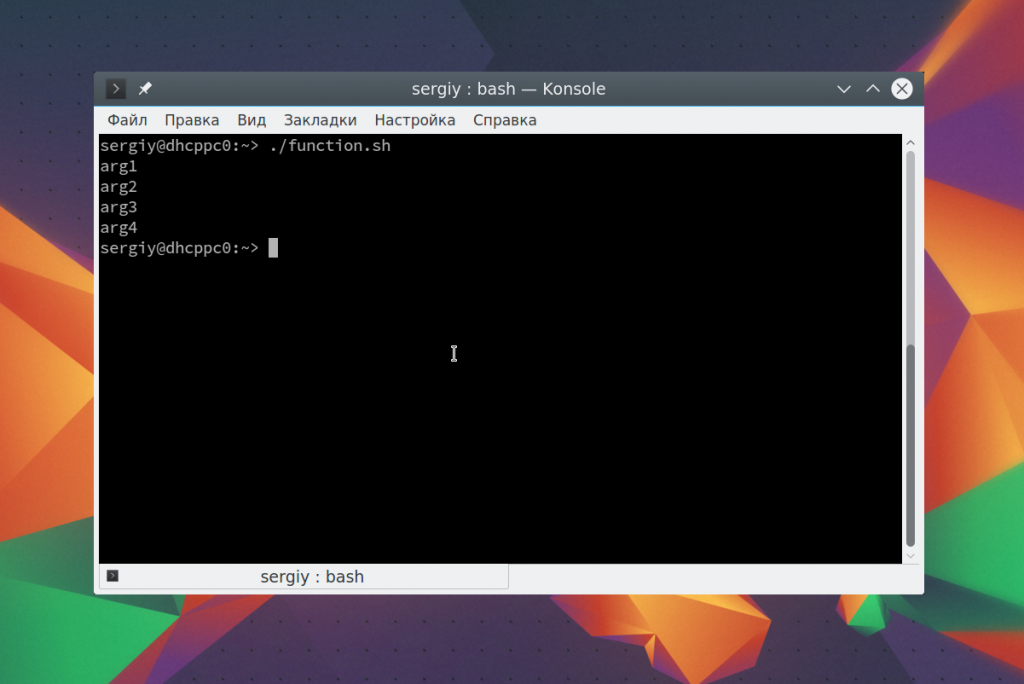

Есть и другой способ извлекать аргументы, как в Си, с помощью стека. Мы извлекаем первый аргумент, затем сдвигаем указатель стека аргументов на единицу и снова извлекаем первый аргумент. И так далее:

!/bin/bash

printstr() echo $1

shift

echo $1

shift

echo $1

shift

echo $1

>

printstr «arg1» «arg2» «arg3» «arg4»

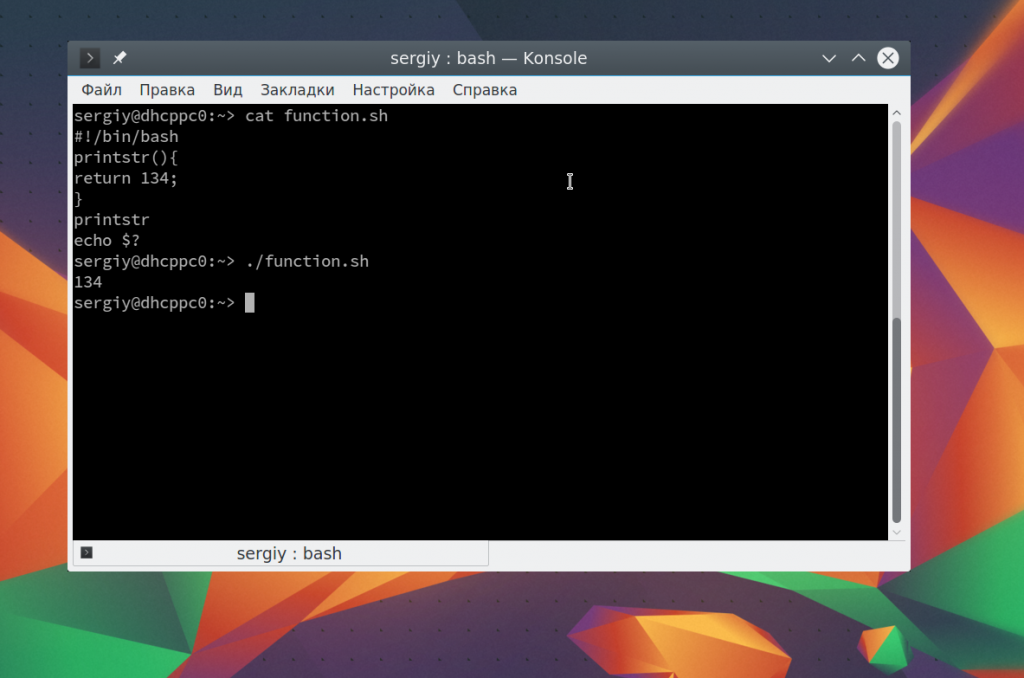

Возврат результата функции

Вы можете не только использовать функции с параметрами bash, но и получить от нее результат работы. Для этого используется команда return. Она завершает функцию и возвращает числовое значение кода возврата. Он может быть от 0 до 255:

!/bin/bash

printstr() return 134;

>

printstr

echo $?

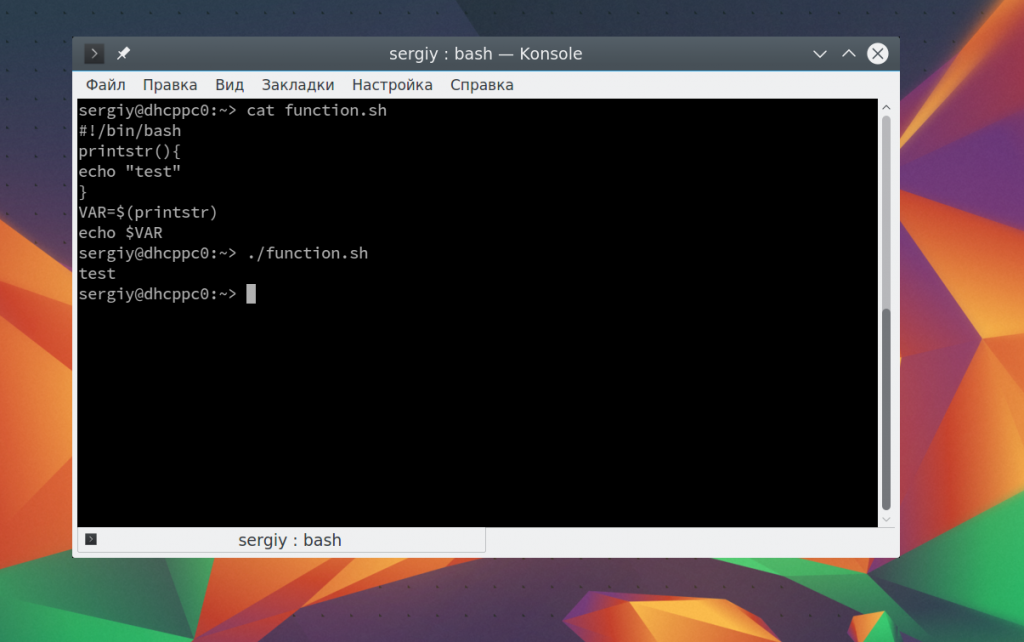

Если вам нужно применить возврат значения функции bash, а не статус код, используйте echo. Строка не сразу выводится в терминал, а возвращается в качестве результата функции и ее можно записать в переменную, а затем использовать:

!/bin/bash

printstr() echo «test»

>

VAR=$(printstr)

echo $VAR

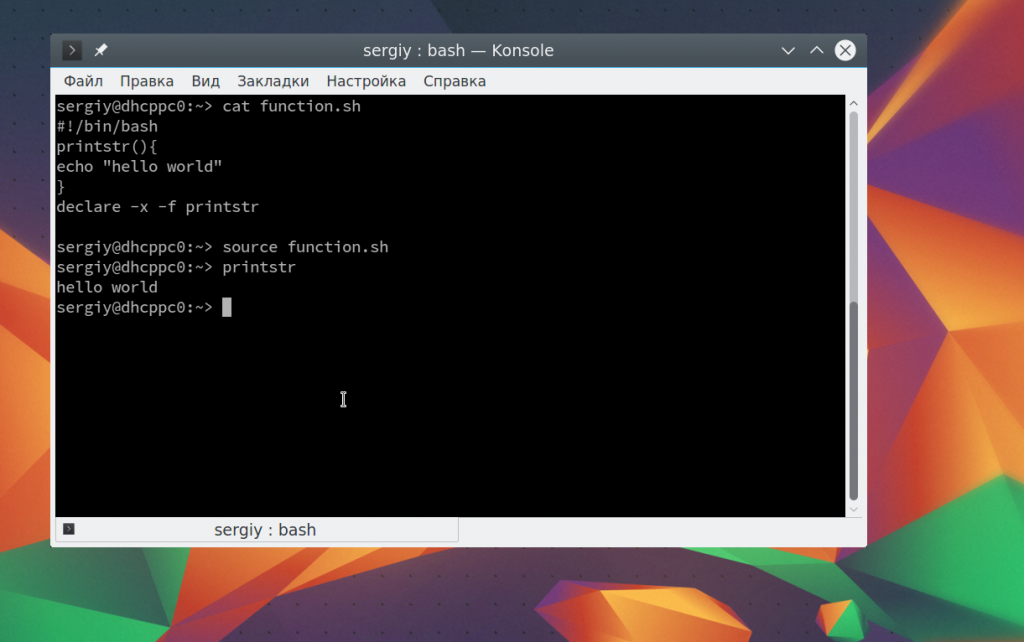

Экспорт функций

Вы можете сделать функцию доступной вне скрипта с помощью команды declare:

!/bin/bash

printstr() echo «hello world»

>

declare -x -f printstr

Затем запустите скрипт с помощью команды source:

source function.sh

$ printstr

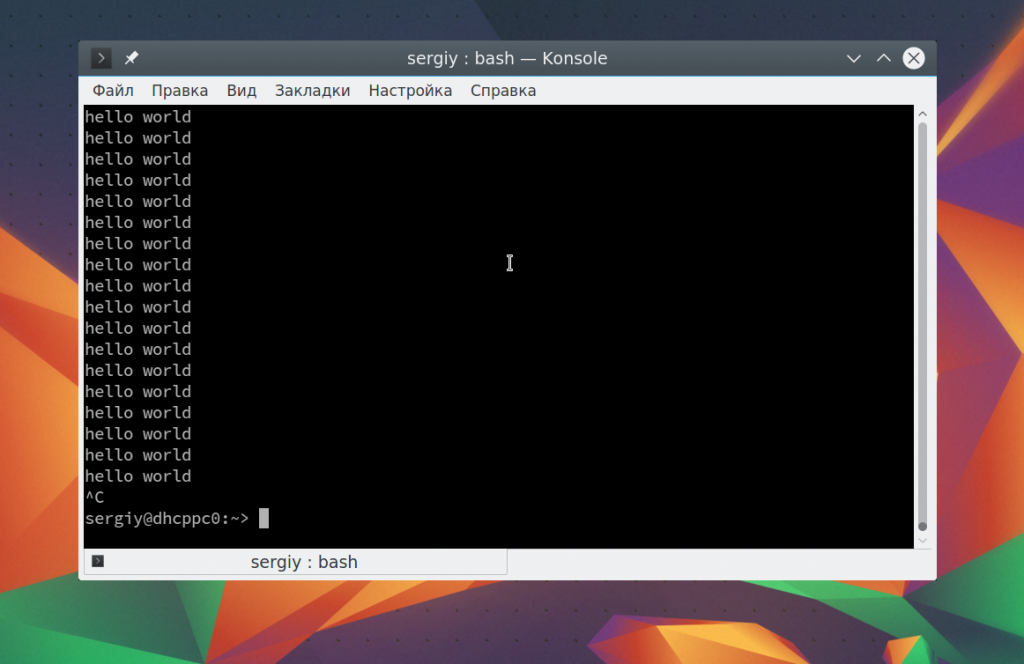

Рекурсия

Вы можете вызвать функцию из нее же самой, чтобы сделать рекурсию:

!/bin/bash

printstr() echo «hello world»

printstr

>

printstr

Вы можете поэкспериментировать с использованием рекурсии, во многих случаях это может быть полезным, только не забывайте делать первый вызов функции Bash.

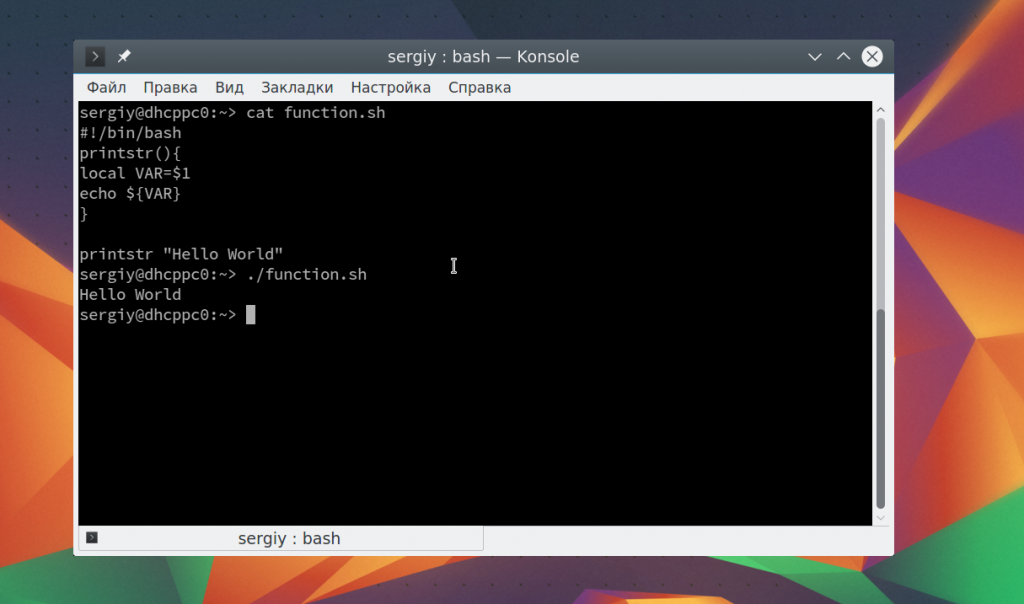

Локальные переменные в функции

Если вы объявите обычную переменную в функции, то она будет доступной во всем скрипте, это удобно для возврата значения функции, но иногда может понадобиться сделать локальную переменную. Для этого существует команда local:

!/bin/bash

printstr() local VAR=$1

echo $

>

printstr «Hello World»

Библиотеки функций

Мы можем взять некоторые функции bash и объединить их в одну библиотеку, чтобы иметь возможность одной командой импортировать эти функции. Это делается похожим образом на экспорт функций. Сначала создадим файл библиотеки:

test1() echo «Hello World from 1»;

>

test2() echo «Hello World from 2»;

>

test3() echo «Hello World from 3»;

>

Теперь создадим скрипт, который будет использовать наши функции. Импортировать библиотеку можно с помощью команды source или просто указав имя скрипта:

!/bin/bash

source lib.sh

test1

test2

test3

Выводы

В этой статье мы рассмотрели функции bash, как их писать, применять и объединять в библиотеки. Если вы часто пишете скрипты на Bash, то эта информация будет для вас полезной. Вы можете создать свой набор функций, для использования их в каждом скрипте и тем самым облегчить себе работу.

Обнаружили ошибку в тексте? Сообщите мне об этом. Выделите текст с ошибкой и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.