How to chown/chmod all files in current directory?

I am trying to change the ownership and permissions of some files (and directories) in the current directory. I tried this:

. expecting that it would affect all the files in the current directory, but instead only affected the directory that I am in (which is the opposite of what I want to do). I want to change it on all the files without affecting the current directory that I am in. How can I chown and chmod all files in current directory?

@Shi I think it’s a fair question. Reading that man page wouldn’t help. Globbing is not part of chmod . It is builtin to the shell. Also reading documentation on globbing sucks the life out of you (I spent way to much time figuring out all the zsh’s features).

5 Answers 5

You want to use chown username:groupname * , and let the shell expand the * to the contents of the current directory. This will change permissions for all files/folders in the current directory, but not the contents of the folders.

You could also do chown -R username:groupname . , which would change the permissions on the current directory, and then recurse down inside of it and all subfolders to change the permissions.

chown -R username:groupname * will change the permissions on all the files and folders recursively, while leaving the current directory itself alone. This style and the first style are what I find myself using most often.

Also, beware of the dangers of the period. As it is placed right next to the almight «/» on the keyboard. A simple typo can easily turn chown -R username:groupname . into chown -R username:groupname / . Making a 2 second task a 2 day nightmare.

Just upvoted as the best and most concise anwser, although I’d be specific and name the directory, just to avoid a slip of the keyboard: chown -R username:groupname directoryname

This doesn’t do all of the files, it ignores the dot files, which were the ones I wanted to chown anyway (the git files needed to be owned by my user so. ) I was able to fix it with chown -R username:groupname ./.*

If you also want to recursively change subdirectories, you’ll need the -R ( -r is deprecated) switch:

chown -R username:groupname *

chown is great if you are a superuser. I had an issue where someone else had run make in my directory, and now owned some files that I could not modify. Here is my workaround which handles files and directories, although it leaves the directories lying around with suffix .mkmeowner if it can’t delete them.

- The following script changes ownership of files and directories passed to it to be owned by the current user, attempting to work around permission issues by making a new copy of every directory or file not owned by the current user, deleting (or trying to delete) the original file, and renaming appropriately.

- The intent is for it to be an abbreviation for «make me owner». I don’t use underscores because they are a pain to type.

% mkmeowner . % mkmeowner dirpath1 dirpath2 #!/bin/bash [ "x$1" == "x-h" ] || [ "x$1" == "x--help" ] && cat \; done #!/bin/bash # change ownership of one file or directory f="$1" expr match "$" '.*\.mkmeowner$' > /dev/null && exit 1 # already tried to do this one if mv -f "$f" "$.mkmeowner"; then cp -pr "$.mkmeowner" "$f" && rm -rf "$.mkmeowner" exit 0 fi exit 1 (1) We prefer answers that include some explanation. I was taken by surprise when I read your scripts and saw what they did, because your introductory paragraph didn’t give me a clue. (2) You forgot to mention that the user must put mkmeownerone into the search PATH. mkmeowner will blow up if that isn’t done. (3) Please learn how (i.e., when and where) to use quotes in shell commands and scripts. Saying $

(Cont’d) … (4) If you run your script on a directory, it will potentially copy every file in that directory twice. (5) expr is antiquated. It’s more efficient to do simple string matching in the shell; bash also supports regular expression matching. For that matter, you could do the filename test in find. (6) Your expr match command tests whether $

(Cont’d) … Now, arguably, this is a good thing — you don’t want to be moving and potentially deleting a script while it’s running. (It’s not necessarily going to cause a problem, but it can be messy.) But you should understand (and document) special cases like that. (7) You might want to use underscores in multi-word strings. dirorfile is hard to read and understand (compare to dir_or_file ), and when I saw mkmeowner , my first thought was of a cat ( mk + meow + ner ).

Thanks for the notes Scott. 1. I thought I did have an explanation but let me be more explicit. 2. good point. I had captured that in my original script, but took out the reference. 3. I’ve been writing shell scripts for 30 years, but sure, I’ll try to learn more. 4. Yes it does. On purpose because if I don’t own the directory, I cannot delete it. I can mention that. 5. Yah I’m old fashioned, but expr still works pretty well 6. ha good point. 7. I might, I think I I get some artistic license though, as underscores are not a rule. I need a script that makes meows!

I don’t think there is anything wrong with $, right? It’s just a little longer than necessary. It’s a format I use often because I may want to use a variable to make a longer string like $.mkmeowner, and I don’t have to remember whether $f.heck means $+heck or $

How to Change File Permissions Recursively with chmod in Linux

Multi-user systems, such as Linux, require setting up and managing file permissions that ensure only authorized users have access to files they are supposed to.

If you need to change a file permission, use the chmod command. It also allows to change the file permission recursively to configure multiple files and sub-directories using a single command.

In this tutorial, you will learn how to use chmod recursively and change file permission on Linux.

Note: The user who creates a file (or directory) has ownership of it. The file-owner has read, write, and execute privileges. Other users only have as much access as given to them when configuring permissions, while the root user has all privileges for all files.

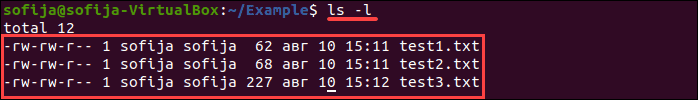

Check File Permission

If you need to check the file permissions in the working directory, use the command:

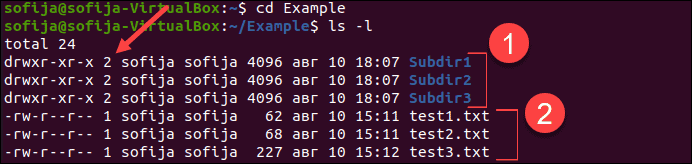

The output lists the permissions of all the files in the directory.

For instance, the Example directory contains three files (test1.txt, test2.txt, and test3.txt) with the same permissions (-rw-rw-r–).

The file permissions listed above tells us the following:

- The owner has read and write privileges

- The owner’s group has read and write privileges

- Other users have read privileges

Note: Do you want to learn more about file permissions and how they are defined? Refer to the Linux File Permission Tutorial.

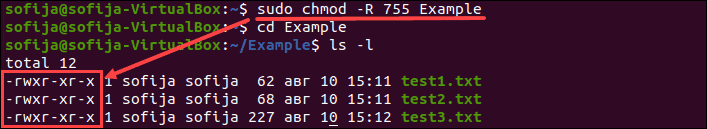

Change Permission Recursively

It is common to use the basic chmod command to change the permission of a single file. However, you may need to modify the permission recursively for all files within a directory.

In such cases, the chmod recursive option ( -R or —recursive ) sets the permission for a directory (and the files it contains).

The syntax for changing the file permission recursively is:

chmod -R [permission] [directory]Therefore, to set the 755 permission for all files in the Example directory, you would type:

The command gives read, write, and execute privileges to the owner (7) and read and execute access to everyone else (55).

Note: In the example above, the permission is defined using the octal/numerical mode ( 755 ). Alternatively, you can utilize the symbolic mode (using alphanumerical characters) and use the command: chmod -R u=rwx,go=rx Example .

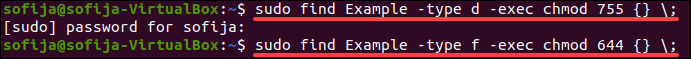

Change Permission With the find Command

To assign separate permissions to directories and files, you can use the find command.

The basic syntax includes using the find command to locate files/directories and then passing it on to chmod to set the permission:

sudo find [directory] -type [d/f] -exec chmod [privilege] <> \;- Replace [directory] with the directory path that holds the files and subdirectories you want to configure.

- Specify whether it is searching for a directory -type d or a file -type f .

- Set the file [privilege] with the chmod command using the numerical or symbolic mode.

Avoid assigning execute privileges to files. A common setup would include running the following commands:

sudo find Example -type d -exec chmod 755 <> \;sudo find Example -type f -exec chmod 644 <> \;In this example, the directories have 755 (u=rwx,go=rx) privileges, while the files have 644 (u=rw,go=r) privileges.

You can check to verify directories and files have different permission settings by moving into the Example directory ( cd Example ) and listing the content ( ls -l ). The output should be similar to the one below:

Note: Learn more about the Linux find command.

Change Permission of Specific Files Recursively

Combining the find command with chmod can also be used for changing the permission of files that are a specific type.

The command syntax for changing the permission of a specific file type in a directory is:

find [directory] -name "*.[filename_extension]" -exec chmod [privilege] <> \;For example, to make all .sh files in the current directory executable, you would use:

find . -name "*.sh" -exec chmod +x <> \;You should now know how to recursively change the file permission on your Linux system with chmod -R or the find command.

Alternatively. you can also use the umask command which lets you change the default permissions.