- How to Enable and Disable Root Login in Ubuntu

- 1. How to Enable Root Account in Ubuntu?

- 2. How to Change Root Password in Ubuntu?

- 3. How to Disable Root Access in Ubuntu?

- User Management

- Where is root?

- Adding and Deleting Users

- User Profile Security

- Password Policy

- Minimum Password Length

- Password Expiration

- Other Security Considerations

- SSH Access by Disabled Users

- External User Database Authentication

- How do I disable root login in Ubuntu?

How to Enable and Disable Root Login in Ubuntu

By default Ubuntu does not set up a root password during installation and therefore you don’t get the facility to log in as root. However, this does not mean that the root account doesn’t exist in Ubuntu or that it can’t be completely accessed. Instead you are given the ability to execute tasks with superuser privileges using sudo command.

Actually, the developers of Ubuntu decided to disable the administrative root account by default. The root account has been given a password which matches no possible encrypted value, thus it may not log in directly by itself.

Attention: Enabling root account is not at all required as most activities in Ubuntu do not actually call for you to use the root account.

Although users are strongly recommended to only use the sudo command to gain root privileges, for one reason or another, you can act as root in a terminal, or enable or disable root account login in the Ubuntu using following ways.

1. How to Enable Root Account in Ubuntu?

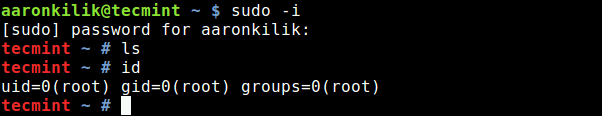

To Access/Enable the root user account run the following command and enter the password you set initially for your user (sudo user).

2. How to Change Root Password in Ubuntu?

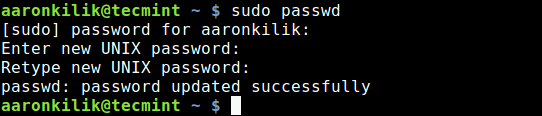

You can change root password with ‘sudo passwd root‘ command as shown below.

$ sudo passwd root Enter new UNIX password: Retype new UNIX password: passwd: password updated successfully

3. How to Disable Root Access in Ubuntu?

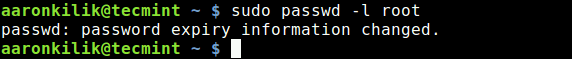

If you wish to disable root account login, run the command below to set the password to expire.

You may refer Ubuntu documentation for further information.

That’s it. In this article, we explained how to enable and disable root login in Ubuntu Linux. Use the comment form below to ask any questions or make any important additions.

User Management

User management is a critical part of maintaining a secure system. Ineffective user and privilege management often lead many systems into being compromised. Therefore, it is important that you understand how you can protect your server through simple and effective user account management techniques.

Where is root?

Ubuntu developers made a conscientious decision to disable the administrative root account by default in all Ubuntu installations. This does not mean that the root account has been deleted or that it may not be accessed. It merely has been given a password hash which matches no possible value, therefore may not log in directly by itself.

Instead, users are encouraged to make use of a tool by the name of ‘sudo’ to carry out system administrative duties. Sudo allows an authorized user to temporarily elevate their privileges using their own password instead of having to know the password belonging to the root account. This simple yet effective methodology provides accountability for all user actions, and gives the administrator granular control over which actions a user can perform with said privileges.

- If for some reason you wish to enable the root account, simply give it a password:

Sudo will prompt you for your password, and then ask you to supply a new password for root as shown below:

[sudo] password for username: (enter your own password) Enter new UNIX password: (enter a new password for root) Retype new UNIX password: (repeat new password for root) passwd: password updated successfully By default, the initial user created by the Ubuntu installer is a member of the group sudo which is added to the file /etc/sudoers as an authorized sudo user. If you wish to give any other account full root access through sudo, simply add them to the sudo group.

Adding and Deleting Users

The process for managing local users and groups is straightforward and differs very little from most other GNU/Linux operating systems. Ubuntu and other Debian based distributions encourage the use of the ‘adduser’ package for account management.

- To add a user account, use the following syntax, and follow the prompts to give the account a password and identifiable characteristics, such as a full name, phone number, etc.

Deleting an account does not remove their respective home folder. It is up to you whether or not you wish to delete the folder manually or keep it according to your desired retention policies. Remember, any user added later on with the same UID/GID as the previous owner will now have access to this folder if you have not taken the necessary precautions. You may want to change these UID/GID values to something more appropriate, such as the root account, and perhaps even relocate the folder to avoid future conflicts:

sudo chown -R root:root /home/username/ sudo mkdir /home/archived_users/ sudo mv /home/username /home/archived_users/ sudo passwd -l username sudo passwd -u username sudo addgroup groupname sudo delgroup groupname sudo adduser username groupname User Profile Security

When a new user is created, the adduser utility creates a brand new home directory named /home/username . The default profile is modeled after the contents found in the directory of /etc/skel , which includes all profile basics.

If your server will be home to multiple users, you should pay close attention to the user home directory permissions to ensure confidentiality. By default, user home directories in Ubuntu are created with world read/execute permissions. This means that all users can browse and access the contents of other users home directories. This may not be suitable for your environment.

- To verify your current user home directory permissions, use the following syntax:

drwxr-xr-x 2 username username 4096 2007-10-02 20:03 username sudo chmod 0750 /home/username Note Some people tend to use the recursive option (-R) indiscriminately which modifies all child folders and files, but this is not necessary, and may yield other undesirable results. The parent directory alone is sufficient for preventing unauthorized access to anything below the parent.

A much more efficient approach to the matter would be to modify the adduser global default permissions when creating user home folders. Simply edit the file /etc/adduser.conf and modify the DIR_MODE variable to something appropriate, so that all new home directories will receive the correct permissions.

drwxr-x--- 2 username username 4096 2007-10-02 20:03 username Password Policy

A strong password policy is one of the most important aspects of your security posture. Many successful security breaches involve simple brute force and dictionary attacks against weak passwords. If you intend to offer any form of remote access involving your local password system, make sure you adequately address minimum password complexity requirements, maximum password lifetimes, and frequent audits of your authentication systems.

Minimum Password Length

By default, Ubuntu requires a minimum password length of 6 characters, as well as some basic entropy checks. These values are controlled in the file /etc/pam.d/common-password , which is outlined below.

password [success=1 default=ignore] pam_unix.so obscure sha512 If you would like to adjust the minimum length to 8 characters, change the appropriate variable to min=8. The modification is outlined below.

password [success=1 default=ignore] pam_unix.so obscure sha512 minlen=8 Note

Basic password entropy checks and minimum length rules do not apply to the administrator using sudo level commands to setup a new user.

Password Expiration

When creating user accounts, you should make it a policy to have a minimum and maximum password age forcing users to change their passwords when they expire.

- To easily view the current status of a user account, use the following syntax:

The output below shows interesting facts about the user account, namely that there are no policies applied:

Last password change : Jan 20, 2015 Password expires : never Password inactive : never Account expires : never Minimum number of days between password change : 0 Maximum number of days between password change : 99999 Number of days of warning before password expires : 7 The following is also an example of how you can manually change the explicit expiration date (-E) to 01/31/2015, minimum password age (-m) of 5 days, maximum password age (-M) of 90 days, inactivity period (-I) of 30 days after password expiration, and a warning time period (-W) of 14 days before password expiration:

sudo chage -E 01/31/2015 -m 5 -M 90 -I 30 -W 14 username Last password change : Jan 20, 2015 Password expires : Apr 19, 2015 Password inactive : May 19, 2015 Account expires : Jan 31, 2015 Minimum number of days between password change : 5 Maximum number of days between password change : 90 Number of days of warning before password expires : 14 Other Security Considerations

Many applications use alternate authentication mechanisms that can be easily overlooked by even experienced system administrators. Therefore, it is important to understand and control how users authenticate and gain access to services and applications on your server.

SSH Access by Disabled Users

Simply disabling/locking a user password will not prevent a user from logging into your server remotely if they have previously set up SSH public key authentication. They will still be able to gain shell access to the server, without the need for any password. Remember to check the users home directory for files that will allow for this type of authenticated SSH access, e.g. /home/username/.ssh/authorized_keys .

Remove or rename the directory .ssh/ in the user’s home folder to prevent further SSH authentication capabilities.

Be sure to check for any established SSH connections by the disabled user, as it is possible they may have existing inbound or outbound connections. Kill any that are found.

who | grep username (to get the pts/# terminal) sudo pkill -f pts/# Restrict SSH access to only user accounts that should have it. For example, you may create a group called “sshlogin” and add the group name as the value associated with the AllowGroups variable located in the file /etc/ssh/sshd_config .

Then add your permitted SSH users to the group “sshlogin”, and restart the SSH service.

sudo adduser username sshlogin sudo systemctl restart sshd.service External User Database Authentication

Most enterprise networks require centralized authentication and access controls for all system resources. If you have configured your server to authenticate users against external databases, be sure to disable the user accounts both externally and locally. This way you ensure that local fallback authentication is not possible.

How do I disable root login in Ubuntu?

a while ago I gave root a password so I could log in as root and get some stuff done. Now I want to disable root login to tighten security, since I’m going to be exposing my serve to the internet. I’ve seen several ways of doing this ( sudo passwd -l root , fiddling with /etc/shadow , and so on), but nowhere that says what the best/most sensible way of doing it is. I’ve done sudo passwd -l root but I’ve seen advice that says this can affect init scripts, and that it’s not as secure as it looks since it still asks for a password if you try to log in, rather than flat out denying access. So what would be the way to achieve that? EDIT: to clarify, this is for local login as root; I’ve already disabled remote login via SSH. Though trying to log in as root over SSH still prompts for root’s password (which always fails). Is that bad?

Disabling local access for root has almost zero security benefit. A user with physical access can pwn your box in countless ways.

Point taken. No need to log in as root if you can just take the hard drives out. I’d still like to know how to return the root account to how it was before I changed it though, if only out of curiosity now.

@jscott while disabling root may not provide security benefit against intrusion, but not logging in as root provides a safety switch against wrecking sys with misplaced rm command or such. Something I learned the hard way. Yes, one simply can NOT log in as root, but disabling it does makes sense from sys admin point of view.