How do I edit configuration files?

I’m a beginner to Ubuntu. Can anyone tell me how to edit a configuration file? This is on Ubuntu 18.04 LTS. Thanks in advance.

Welcome to Ask Ubuntu, please edit your post and provide more details, what do you exactly want to do?

Which files did you want to edit? I am asking because some files require root privileges and some highly recommend that you run a command specifically for editing them (example visudo for the sudoers file or crontab -e for adding cron entries)

4 Answers 4

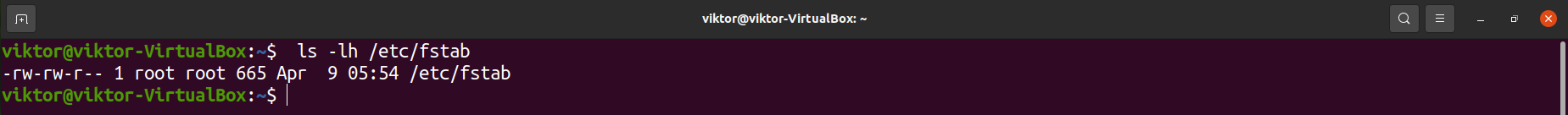

Configuration files are usually owned by root . For example:

$ ll /etc/default/grub -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 6801 Jul 18 13:26 /etc/default/grub ^^ ^ ^ || | +-- Users can only read || +----- Members of the group can only read |+------- The owner can write +-------- The owner can read In order for a user (yourself) to edit /etc/grub/default you need to use sudo powers. So instead of using:

You must use:

sudo -H gedit /etc/default/grub At which point you will be prompted for your password.

The answer depends on which configuration file you want to edit. Most are text files that can be edited with admin privileges. Some are not. For example Firefox configuration should be done from inside Firefox using about:config page.

@user68186 Yes there are all kinds of specialized solutions like you mention. However generically most of the default packages in Ubuntu require sudo to edit configuration files like grub , plymouth , systemd , etc. These are just examples of booting the system. There are many more applications after system is booted that also require sudo . I believe this to be the spirit of the question. Adding all the exceptions would make all the answers a textbook.

@AndreaLazzarotto In the old days I created sgedit script which copies users profile for gedit to root so I actually don’t even use sudo -H gedit except buried within that script. i think there is a gksu gedit Q&A or two here in Ask Ubuntu where gedit admin:/// would be a great answer for you to post. Please let me know when you do and I’ll check it out.

System-wide configuration files, which are often in /etc , are owned by root and you need to elevate your privileges to edit them. It’s common to run a text editor as root with sudo , and other answers here show how. But just because only root can make changes the files does not mean you have to run your text editor as root. You can instead use sudoedit , which is documented in the same manpage as sudo .

For example, to edit /etc/hosts :

The way this works is that sudoedit :

- Checks if you’ve recently authenticated with sudo from the terminal you’re in (like sudo does), an prompts you for your password if you haven’t.

- Checks if it is clear that could just edit the file normally, without sudoedit or sudo . If so, it gives you an error message and quits. (In this situation, you should just edit the file normally as DK Bose says, assuming it makes sense to do so.)

- Makes a temporary copy of the file, opens that file in a text editor, and waits for the editor to quit.

- Checks if the file has changed, and updates the original if it has.

sudoedit works with your choice of text editor. To edit with nano :

VISUAL=nano sudoedit /etc/hosts It even works with GUI editors like Gedit:

VISUAL=gedit sudoedit /etc/hosts Furthermore, because the editor is run as you, it uses your configuration, so if you’ve customized the behavior of your editor, those customizations are used. Other ways of attempting this tend not to work very well.

You can set the VISUAL environment variable persistently for your user to make sudoedit , and various other commands that need to pick an editor, use your preferred editor. If you want to set an editor just for sudoedit (and visudo ) but not other programs, set SUDO_EDITOR instead of VISUAL .

Because the logic of checking if two files are the same and copying one onto another is simpler than the full logic of a text editor—and especially simpler than the full operation of a graphical program like Gedit—running sudoedit might be considered more secure in the specific sense that it is associated with a smaller attack surface. Running less stuff as root is good. But the main reason to use sudoedit is convenience.

Because sudoedit is so useful and versatile, its benefits are sometimes overstated. It’s a good tool, but you don’t have to use it, and using it instead of other methods doesn’t affect security in any decisive way. If you change system-wide configuration files in a way that breaks things, they will still break! That seems obvious when stated that way, but sometimes people try to give users the right to edit files owned by root with sudoedit while still trying to restrain those users in some way through technical measures. This is not usually practical.

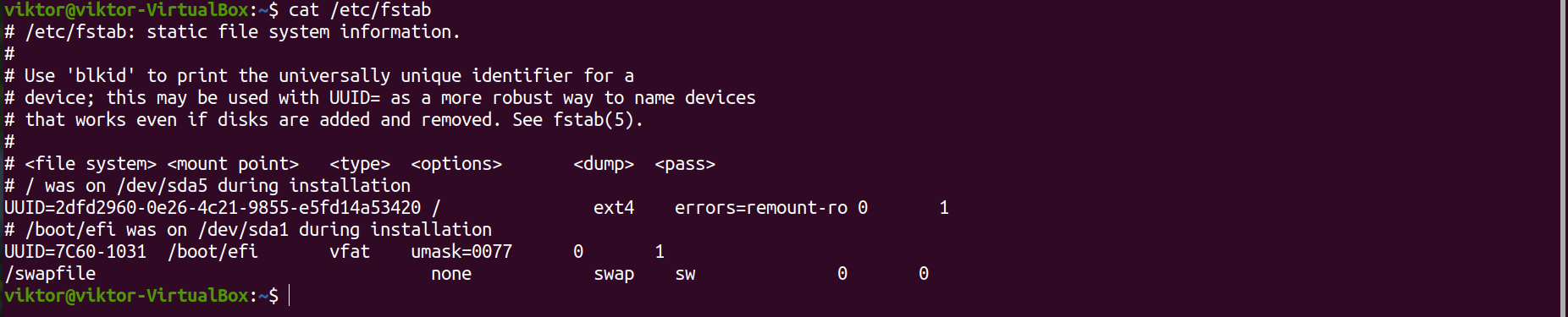

How to Write or Edit /etc/fstab

In Linux, there are multiple system configuration files that regulate system behavior. The fstab file is such a configuration file that stores all the information about various partitions and storage devices on the computer. At the time of boot, the fstab file describes how each partition and device will mount.

Let’s dive deep into the “/etc/fstab” file.

The fstab file

As described earlier, it’s a configuration file holding information about partitions, devices, and mount configurations. It’s located at the following location.

It’s a plain text file, so we can use any text editor of our choice to work with it. However, it requires root permission to write changes to it.

Basics

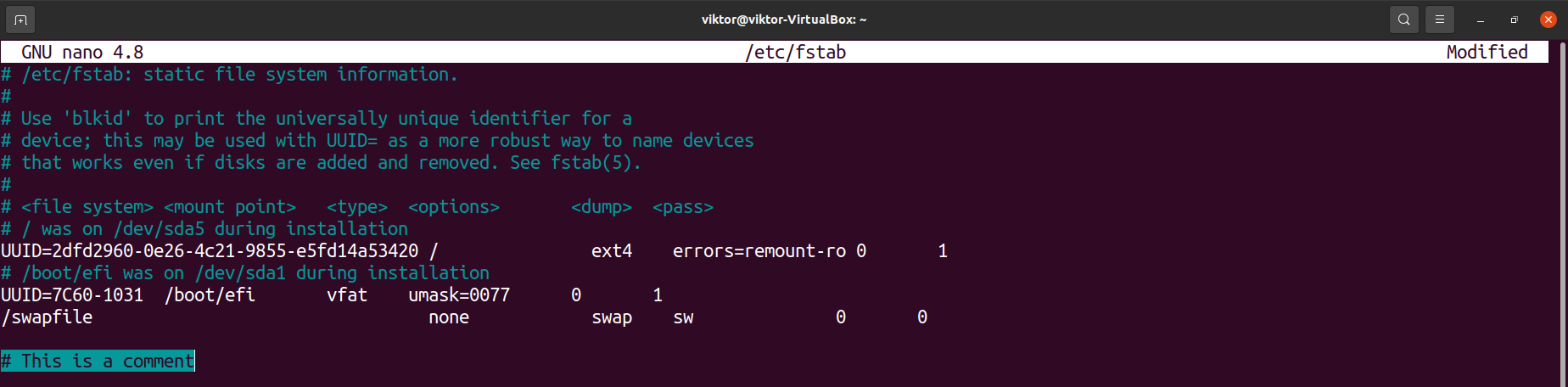

First, have a look at the fstab file in your system. Note that each system will have different entries because of the partition and hardware differences. However, all fstab files will share the same fundamental structure.

Each line of the file is dedicated to a unique device/partition. It’s divided into six columns. Here’s a brief description of each of the columns.

- Column 1: Device name.

- Column 2: Default mount point.

- Column 3: Filesystem type.

- Column 4: Mount options.

- Column 5: Dump options.

- Column 6: Filesystem check options.

Device name

It’s the label of the particular device/partition. Each device and partition gets its unique device name. The device name is essential for mounting devices, partitions, and filesystems.

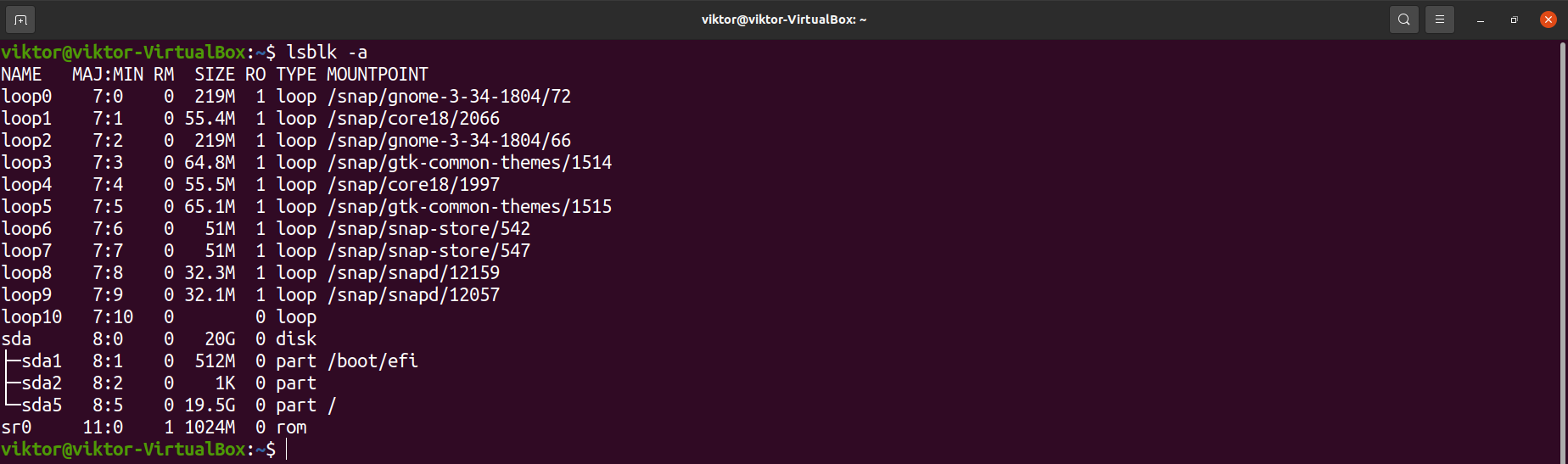

We can use the lsblk command to get a report on all the block devices. It practically reports all the gadgets and partitions with their device names.

Default mount point

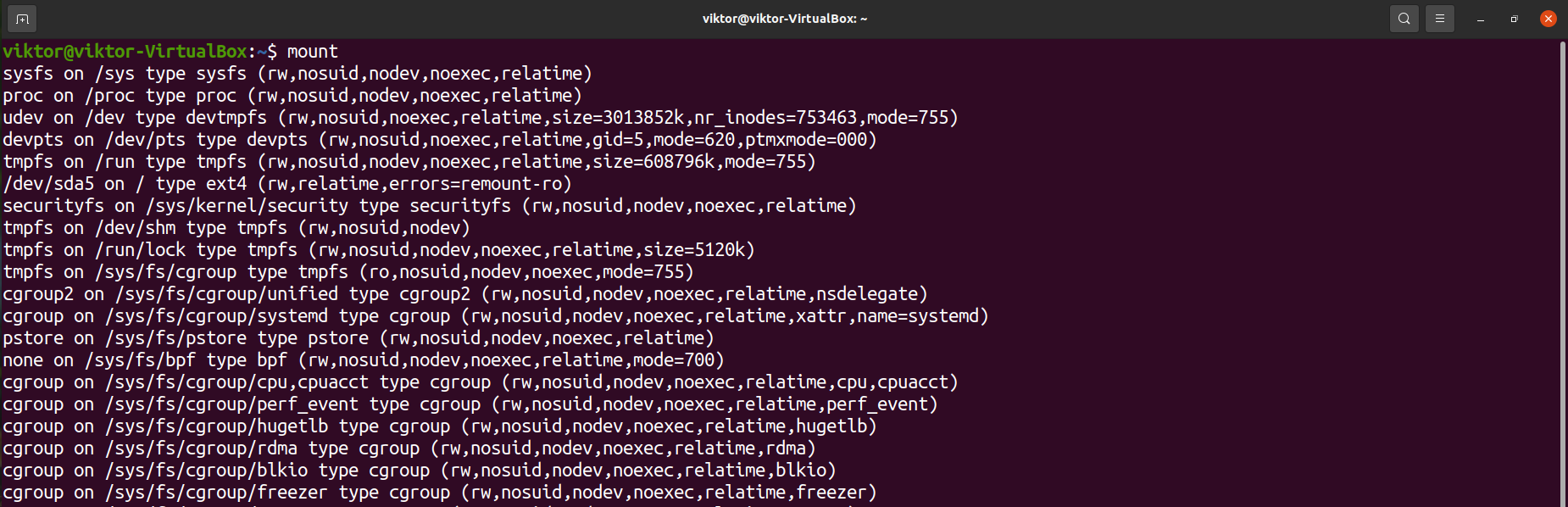

In Linux, a device, partition, or filesystem must be mounted on a location before the system can use it. Mounting makes the filesystem accessible through the computer’s filesystem. The mount point is the directory access to the device, partition, or filesystem.

We can get a list of all the mounted partitions on the system.

In the context of the fstab file, the mount point described for the specific device name will be used as the default mount point. When the computer boots, the system will mount all the devices to the mount points described in this file.

Filesystem type

A filesystem can be described as an index of the database with all the physical location of data on the storage. There are numerous filesystems used widely. Linux supports several filesystems by default. Here’s a shortlist of the popular filesystems.

Another option is “auto,” which lets the system auto-detect the filesystem type of the device or partition. Use this option if you’re not confident about the specific filesystem.

Mount options

The mount options determine the mounting behavior of the device/partition. It’s considered the most confusing part of the fstab file.

Here’s a shortlist of some of the common mount options you’ll come across when working with the fstab file.

- auto and noauto: This option determines if the system will mount the filesystem during boot. By default, the value is “auto,” meaning it’ll be mounted during boot. However, in specific scenarios, the “noauto” option may be applicable.

- user and nouser: It describes which user can mount the filesystem. If the value is “user,” then normal users can mount the filesystem. If the value is “nouser,” then only the root can mount it. By default, the value is “user.” For specific and critical filesystems, “nouser” can be helpful.

- exec and noexec: It describes whether binaries can be executed from the filesystem. The value “exec” allows binary execution, whereas “noexec” does not. The default value is “exec” for all partitions.

- sync and async: It determines how the input and output to the device/partition will be performed. If the value is “sync,” then input and output are done synchronously. If the value is “async,” then it’s done asynchronously. It affects how data is read and written.

- ro: It describes that the partition is to be treated as read-only. Data on the filesystem can’t be changed.

- rw: It describes that the partition is available for reading and writing data.

Dump

It describes whether the filesystem is to be backed up. If the value is 0, then the dump will ignore the filesystem. In most cases, it’s assigned 0. For backup, it’s more convenient to use various third-party tools.

Fsck options

The fsck tool checks the filesystem. The value assigned in this column determines in which order fsck will check the listed filesystems.

Editing fstab file

Before editing the fstab file, it’s always recommended to have a backup.

Before making any changes to the fstab file, it’s recommended to make a backup first. It contains critical configuration details, so wrong entries may cause unwanted results.

To edit the fstab file, launch your text editor of choice with sudo.

To write a comment, use “#” at the start.

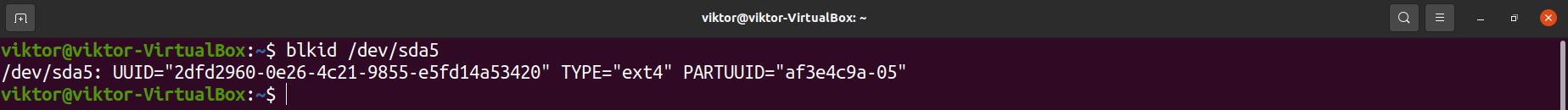

Note that some entries may use the device UUID instead of a device name. To get the UUID of a device, use blkid.

After all the changes are made, save the file and close the editor. These changes won’t be effective unless the system restarts.

Final thoughts

The fstab file is a simple yet powerful solution to many situations. It can also automate mounting remote filesystems. It just requires understanding the code structure and supported options to take the full benefit of it.

For more in-depth info, check the man page.