Patching a binary with dd

I have read this quote (below) several times, most recently here, and am continually puzzled at how dd can be used to patch anything let alone a compiler:

The Unix system I used at school, 30 years ago, was very limited in RAM and Disk space. Especially, the /usr/tmp file system was very small, which led to problems when someone tried to compile a large program. Of course, students weren’t supposed to write «large programs» anyway; large programs were typically source codes copied from «somewhere». Many of us copied /usr/bin/cc to /home//cc , and used dd to patch the binary to use /tmp instead of /usr/tmp , which was bigger. Of course, this just made the problem worse — the disk space occupied by these copies did matter those days, and now /tmp filled up regularly, preventing other users from even editing their files. After they found out what happened, the sysadmins did a chmod go-r /bin/* /usr/bin/* which «fixed» the problem, and deleted all our copies of the C compiler.

(Emphasis mine) The dd man-page says nothing about patching and a don’t think it could be re-purposed to do this anyway. Could binaries really be patched with dd ? Is there any historical significance to this?

Sure — just od a file for the byte hex codes, find the offset you need, decide on your edit, and bs=$patchsize count=1 seek=$((offset/bs)) conv=notrunc your patch right on in.

@ParthianShot Actually I overwrote the first ~260MB of my boot drive (+ root) with part of a Debian LiveCD once. O_o But I don’t think that is really patching, hehehe.

3 Answers 3

Let’s try it. Here’s a trivial C program:

#include int main(int argc, char **argv) < puts("/usr/tmp"); >We’ll build that into test :

If we run it, it prints «/usr/tmp».

Let’s find out where » /usr/tmp » is in the binary:

$ strings -t d test | grep /usr/tmp 1460 /usr/tmp -t d prints the offset in decimal into the file of each string it finds.

Now let’s make a temporary file with just » /tmp\0 » in it:

So now we have the binary, we know where the string we want to change is, and we have a file with the replacement string in it.

$ dd if=tmp of=test obs=1 seek=1460 conv=notrunc This reads data from tmp (our » /tmp\0 » file), writing it into our binary, using an output block size of 1 byte, skipping to the offset we found earlier before it writes anything, and explicitly not truncating the file when it’s done.

We can run the patched executable:

The string literal the program prints out has been changed, so it now contains » /tmp\0tmp\0 «, but the string functions stop as soon as they see the first null byte. This patching only allows making the string shorter or the same length, and not longer, but it’s adequate for these purposes.

So not only can we patch things using dd , we’ve just done it.

This is excellent. and something I strongly hope I never encounter in a production environment! I have used similar methods in the past to get serial numbers into hex images for microcontrollers, it’s far too easy to shoot yourself in the foot though.

If i wanted to give written instructions to someone how to patch a particular binary, i’d rather give them a command line to copy/paste than tell them «open the file in a hex editor, find the /usr/tmp string, replace it with /tmp , don’t forget the trailing \0 byte, save the file, and cross your fingers». Or, even better, a shell script that does some sanity checking first, then calls dd . Unfortunately, the need for stuff like this arises frequently when an old piece of software by a now-defunct vendor just has to be migrated to a new system.

Yeah, sed’s better for this kind of thing. But you’re not completely right about the whole «This patching only allows making the string shorter or the same length, and not longer». You’re assuming that you care about the data immediately following the string you want to modify, or that you can’t have the next string simply be a substring of the original string. In other words, if you’re in the .strings section of memory, and you’ve got «/usr\0/bin/bash\0», you can turn that into /usr/bin/bash by simply changing that first null byte and making it «/usr//bin/bash» (for example).

@ParthianShot — sed ‘s not better for this kind of thing — you cannot so expliciltly and precisely limit sed ‘s read/write buffers in the way you might with dd — which is the whole reason it was ever used for this in the first place. With dd you can arbitrarily place an arbitrary count of arbitrary bytes. This cannot also be said of sed . If dd is used like a scalpel here, you would apply sed like a wrecking ball.

That’s a fair (albeit fairly rare!) point — there will be occasions when you can make the string longer by not caring about either the result or another arbitrary, but specific, piece of data. I’ll stand by the general statement, though.

It depends on what you mean by «patch the binary».

I change binaries using dd sometimes. Of course there is no such feature in dd , but it can open files, and read and write things at specific offsets, so if you know what to write where, voila there is your patch.

For example I had this binary that contained some PNG data. Use binwalk to find the offset, dd to extract it (usually binwalk also extracts things but my copy was buggy), edit it with gimp , make sure the edited file is same size or smaller than the original one (changing offsets is not something you can do easily), and then use dd to put the changed image back in place.

$ binwalk thebinary […] 4194643 0x400153 PNG image, 800 x 160, 8-bit/color RGB, non-interlaced […] $ dd if=nickel bs=1 skip=4194641 count=2 conv=swab | od -i 21869 # file size in this case - depends on the binary format $ dd if=thebinary bs=1 skip=4194643 count=21869 of=theimage.png $ gimp theimage.png $ pngcrush myimage.png myimage.crush.png # make sure myimage.crush.png is smaller than the original $ dd if=myimage.crush.png of=thebinary bs=1 seek=4194643 conv=notrunc Sometimes I also wish to replace strings in binaries (such as path or variable names). While this could also be done using dd , it is simpler to do so using sed . You just have to make sure the string you replace with has the same length as the original string so you don’t end up changing offsets.

sed -e s@/the/old/save/path@/the/new/save/path@ -i thebinary or to pick up @MichaelHomer’s example with a 0-byte added in:

sed -e 's@/usr/tmp@/tmp\x00tmp@' -i test Of course you have to verify whether it actually works afterwards.

Binary Patching Using Radare2

This blog post will talk about using radare2 to patch a binary on the linux platform. You can read this tutorial with no knowledge of radare, but you will get a lot more out it if you have some basic knowledge about how to use radare.

A Brief Introduction to concepts used in this blog post

Radare2

Radare2 is an open source reverse engineering framework that supports a large number of different processors and platforms. Radare2 is similar to tools like IDA pro, Binary Ninja and Ghidra, but the main difference is that radare runs inside of a terminal window. This is nice because it means that radare can be used over a ssh connection or on low power machines. Radare has a lot of awesome features, but this tutorial will focus on the main tool r2 .

Binary patching

Binary patching is the process of modifying a compiled executable to change the code that is run. Radare allows for assembly code to be written inline, compiled and inserted into the binary without any hassle.

Okay lets patch a binary

Getting a binary to patch

First off lets get a binary to patch. Here is some source code from challenges.re challenge 55.

#include void printing_function(int i) printf ("f(%d)\n", i); >; int main() int i; for (i=2; i10; i++) printing_function(i); return 0; >;Compile this using gcc -o patcher patcher.c then make a copy of the binary that we can mess up on when we try to patch it using cp patcher test .

Reverse time

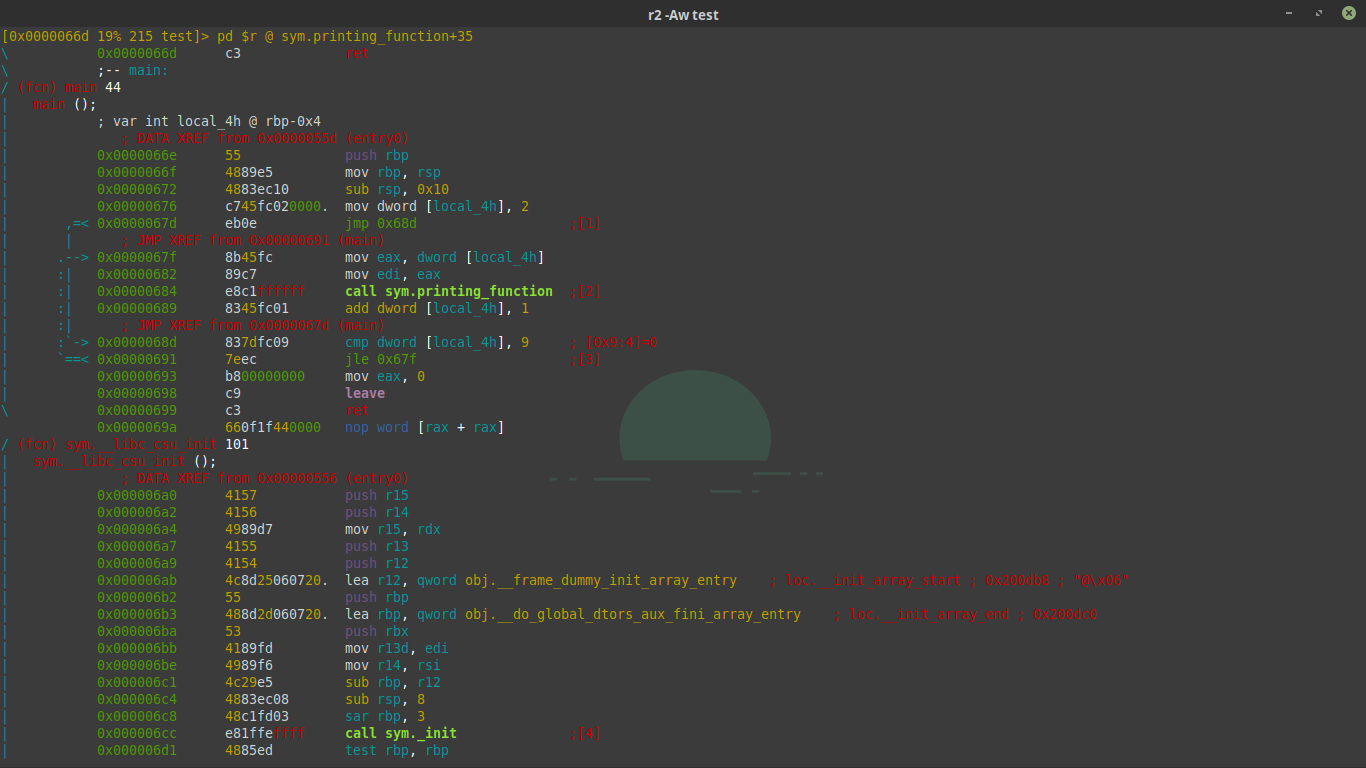

Fist of we need to open the binary in radare with write capabilities. Run the command r2 -w test and you will be presented with a radare prompt. Next we need to analyze the binary. From the prompt type in aaa this will tell radare to anaylize all things apart of the binary. To make this simple we can go in with the assumption that we know the program is written in c. Think to yourself “what is function exists in every c program”. If you answered main you are correct. Next we need to seek to the main function. The radare command to do this is very simple ‘s main’. Now we are at the location of main. After this type the following command V you will then see the terminal change don’t panic or hit any keys. You are in the default visual mode, the hex editor, we need to swap into the inline disasembler. To do that hit the ‘p’ key. You should be prompted with something that looks like this.

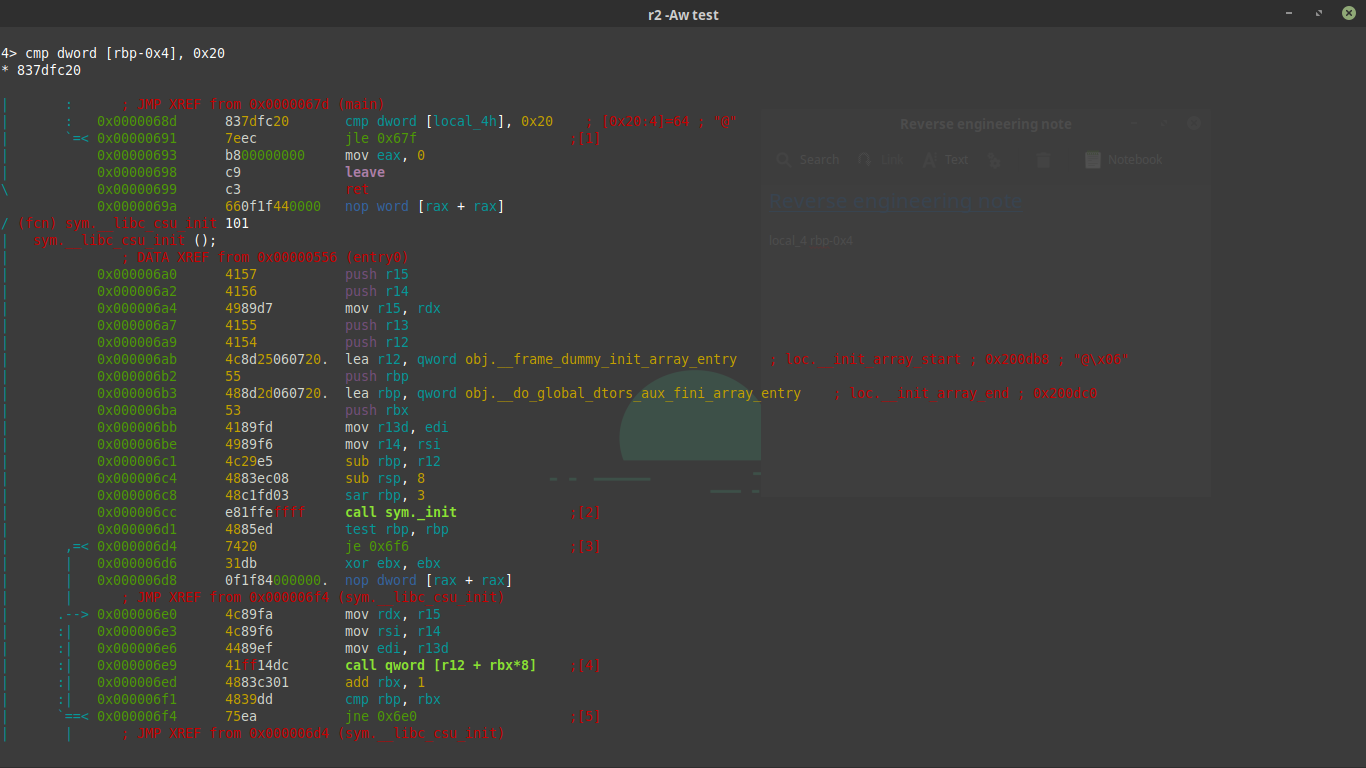

From here you can navigate the disassembly using the arrow keys or J and K like in vim. Radare makes it very easy to see what variables are mapped to what stack offset. In this case we can see the variable local_4h that is mapped to rbp-0x4 with the type int. We also see the structure of a for loop starting at the jmp 0x68d instruction and the comaprison statement where the value of local_4h is compared to 9. We also see the function sym.printing_function being called with the value of local_4h . What if we wanted to make it so that printing function was called say… 32 times. We would change the cmp instruction to cmp dword [local_4h_addr], 0x20 , but how do we do that? The answer is patching the binary using radare’s awesome patching powers. First “scroll” down to the cmp line and press the capital A key. You will be presented with a prompt that allows you to type assembly and have it be compiled and inserted in the place of the cmp line. Here is what it will look like. The assembly to insert is cmp dword [rbp-0x4], 0x20

To finish off the patch hit enter and then hit q to exit the visual mode and then q enter to exit radare. If you opened the binary in write mode you should be able to run ./test and get a different output then that of ./patcher Congrats you have patched your first binary.

Here is a gif from BBC’s James May: The Reassembler to celebrate your reverse engineering adventure.