- Viewing and monitoring log files

- What you’ll learn

- What you’ll need

- How will you use this tutorial?

- What is your current level of experience?

- 2. Log files locations

- System logs

- Authorization log

- Daemon Log

- Debug log

- Kernel log

- System log

- Application logs

- Apache logs

- X11 server logs

- Non-human-readable logs

- Login failures log

- Last logins log

- Login records log

- 3. Viewing logs using GNOME System Log Viewer

- System Log Viewer interface

- More information

- 4. Viewing and monitoring logs from the command line

- Viewing files

- Viewing the start or end of a file

- Monitoring files

- Searching files

- Editing files

- 5. Conclusion

- Further reading

- Classic SysAdmin: Viewing Linux Logs from the Command Line

- /var/log

- Viewing logs with less

- Viewing logs with dmesg

- Viewing logs with tail

- There are other tools

Viewing and monitoring log files

The Linux operating system, and many applications that run on it, do a lot of logging. These logs are invaluable for monitoring and troubleshooting your system.

What you’ll learn

- Viewing logs with a simple GUI tool

- Basic command-line commands for working with log files

What you’ll need

Originally authored by Ivan Fonseca.

How will you use this tutorial?

What is your current level of experience?

2. Log files locations

There are many different log files that all serve different purposes. When trying to find a log about something, you should start by identifying the most relevant file. Below is a list of common log file locations.

System logs

System logs deal with exactly that — the Ubuntu system — as opposed to extra applications added by the user. These logs may contain information about authorizations, system daemons and system messages.

Authorization log

Keeps track of authorization systems, such as password prompts, the sudo command and remote logins.

Daemon Log

Daemons are programs that run in the background, usually without user interaction. For example, display server, SSH sessions, printing services, bluetooth, and more.

Debug log

Provides debugging information from the Ubuntu system and applications.

Kernel log

Logs from the Linux kernel.

System log

Contains more information about your system. If you can’t find anything in the other logs, it’s probably here.

Application logs

Some applications also create logs in /var/log . Below are some examples.

Apache logs

Location: /var/log/apache2/ (subdirectory)

Apache creates several log files in the /var/log/apache2/ subdirectory. The access.log file records all requests made to the server to access files. error.log records all errors thrown by the server.

X11 server logs

The X11 server creates a seperate log file for each of your displays. Display numbers start at zero, so your first display (display 0) will log to Xorg.0.log . The next display (display 1) would log to Xorg.1.log , and so on.

Non-human-readable logs

Not all log files are designed to be read by humans. Some were made to be parsed by applications. Below are some of examples.

Login failures log

Contains info about login failures. You can view it with the faillog command.

Last logins log

Contains info about last logins. You can view it with the lastlog command.

Login records log

Contains login info used by other utilities to find out who’s logged in. To view currently logged in users, use the who command.

This is not an exhaustive list!

You can search the web for more locations relevant to what you’re trying to debug. There is also a longer list here.

3. Viewing logs using GNOME System Log Viewer

The GNOME System Log Viewer provides a simple GUI for viewing and monitoring log files. If you’re running Ubuntu 17.10 or above, it will be called Logs. Otherwise, it will be under the name System Log.

System Log Viewer interface

The log viewer has a simple interface. The sidebar on the left shows a list of open log files, with the contents of the currently selected file displayed on the right.

The log viewer not only displays but also monitors log files for changes. The bold text (as seen in the screenshot above) indicates new lines that have been logged after opening the file. When a log that is not currently selected is updated, it’s name in the file list will turn bold (as shown by auth.log in the screenshot above).

Clicking on the cog at the top right of the window will open a menu allowing you to change some display settings, as well as open and close log files.

There is also a magnifying glass icon to the right of the cog that allows you to search within the currently selected log file.

More information

If you wish to learn more about the GNOME System Log Viewer, you may visit the official documentation.

4. Viewing and monitoring logs from the command line

It is also important to know how to view logs in the command line. This is especially useful when you’re remotely connected to a server and don’t have a GUI.

The following commands will be useful when working with log files from the command line.

Viewing files

The most basic way to view files from the command line is using the cat command. You simply pass in the filename, and it outputs the entire contents of the file: cat file.txt .

This can be inconvenient when dealing with large files (which isn’t uncommon for logs!). We could use an editor, although that may be overkill just to view a file. This is where the less command comes in. We pass it the filename ( less file.txt ), and it will open the file in a simple interface. From here, we can use the arrow keys (or j/k if you’re familiar with Vim) to move through the file, use / to search, and press q to quit. There are a few more features, all of which are described by pressing h to open the help.

Viewing the start or end of a file

We may also want to quickly view the first or last n number of lines of a file. This is where the head and tail commands come in handy. These commands work much like cat , although you can specify how many lines from the start/end of the file you want to view. To view the first 15 lines of a file, we run head -n 15 file.txt , and to view the last 15, we run tail -n 15 file.txt . Due to the nature of log files being appended to at the bottom, the tail command will generally be more useful.

Monitoring files

To monitor a log file, you may pass the -f flag to tail . It will keep running, printing new additions to the file, until you stop it (Ctrl + C). For example: tail -f file.txt .

Searching files

One way that we looked at to search files is to open the file in less and press / . A faster way to do this is to use the grep command. We specify what we want to search for in double quotes, along with the filename, and grep will print all the lines containing that search term in the file. For example, to search for lines containing “test” in file.txt , you would run grep «test» file.txt .

If the result of a grep search is too long, you may pipe it to less , allowing you to scroll and search through it: grep «test» file.txt | less .

Editing files

The simplest way to edit files from the command line is to use nano . nano is a simple command line editor, which has all the most useful keybindings printed directly on screen. To run it, just give it a filename ( nano file.txt ). To close or save a file, press Ctrl + X. The editor will ask you if you want to save your changes. Press y for yes or n for no. If you choose yes, it will ask you for the filename to save the file as. If you are editing an existing file, the filename will already be there. Simply leave it as it is and it will save to the proper file.

5. Conclusion

Congratulations, you now have enough knowledge of log file locations, usage of the GNOME System Log Viewer and basic command line commands to properly monitor and trouble-shoot problems that arise on your system.

Further reading

- The Ubuntu Wiki has an article that goes more in-depth into Ubuntu log files.

- This DigitalOcean Community article covers viewing Systemd logs

Classic SysAdmin: Viewing Linux Logs from the Command Line

This is a classic article written by Jack Wallen from the Linux.com archives. For more great SysAdmin tips and techniques check out our free intro to Linux course.

At some point in your career as a Linux administrator, you are going to have to view log files. After all, they are there for one very important reason…to help you troubleshoot an issue. In fact, every seasoned administrator will immediately tell you that the first thing to be done, when a problem arises, is to view the logs.

And there are plenty of logs to be found: logs for the system, logs for the kernel, for package managers, for Xorg, for the boot process, for Apache, for MySQL… For nearly anything you can think of, there is a log file.

Most log files can be found in one convenient location: /var/log. These are all system and service logs, those which you will lean on heavily when there is an issue with your operating system or one of the major services. For desktop app-specific issues, log files will be written to different locations (e.g., Thunderbird writes crash reports to ‘~/.thunderbird/Crash Reports’). Where a desktop application will write logs will depend upon the developer and if the app allows for custom log configuration.

We are going to be focus on system logs, as that is where the heart of Linux troubleshooting lies. And the key issue here is, how do you view those log files?

Fortunately there are numerous ways in which you can view your system logs, all quite simply executed from the command line.

/var/log

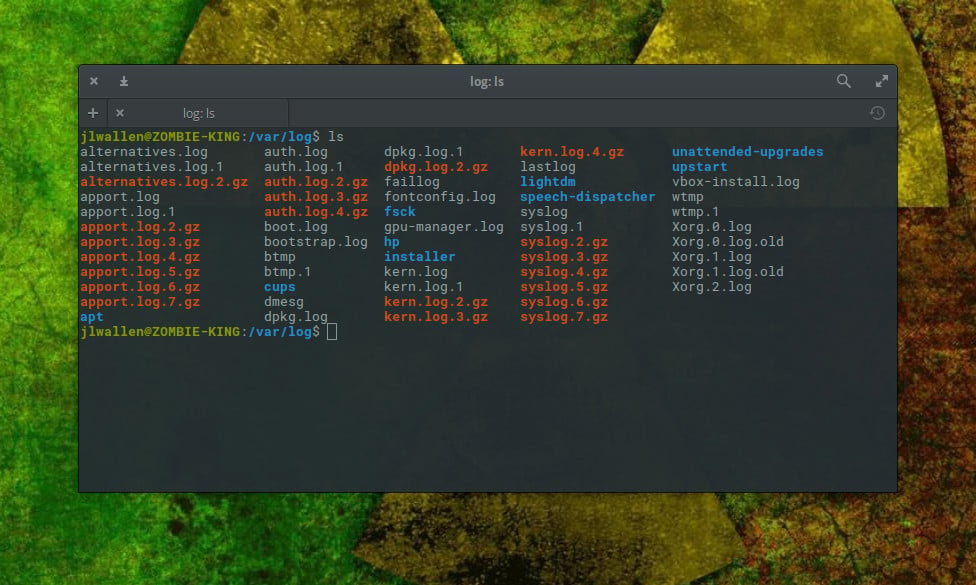

This is such a crucial folder on your Linux systems. Open up a terminal window and issue the command cd /var/log. Now issue the command ls and you will see the logs housed within this directory (Figure 1).

Now, let’s take a peek into one of those logs.

Viewing logs with less

One of the most important logs contained within /var/log is syslog. This particular log file logs everything except auth-related messages. Say you want to view the contents of that particular log file. To do that, you could quickly issue the command less /var/log/syslog. This command will open the syslog log file to the top. You can then use the arrow keys to scroll down one line at a time, the spacebar to scroll down one page at a time, or the mouse wheel to easily scroll through the file.

The one problem with this method is that syslog can grow fairly large; and, considering what you’re looking for will most likely be at or near the bottom, you might not want to spend the time scrolling line or page at a time to reach that end. Will syslog open in the less command, you could also hit the [Shift]+[g] combination to immediately go to the end of the log file. The end will be denoted by (END). You can then scroll up with the arrow keys or the scroll wheel to find exactly what you want.

This, of course, isn’t terribly efficient.

Viewing logs with dmesg

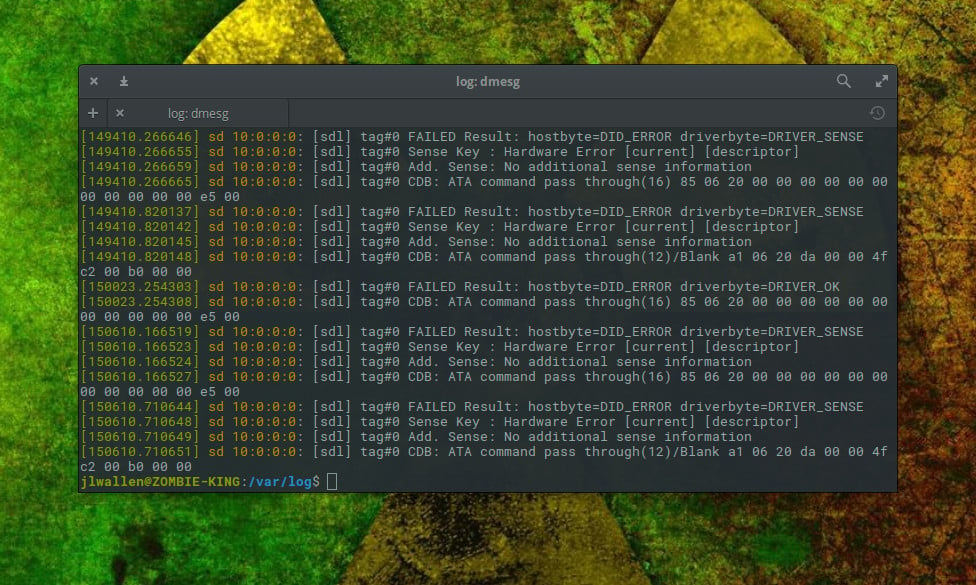

The dmesg command prints the kernel ring buffer. By default, the command will display all messages from the kernel ring buffer. From the terminal window, issue the command dmesg and the entire kernel ring buffer will print out (Figure 2).

Fortunately, there is a built-in control mechanism that allows you to print out only certain facilities (such as daemon).

Say you want to view log entries for the user facility. To do this, issue the command dmesg –facility=user. If anything has been logged to that facility, it will print out.

Unlike the less command, issuing dmesg will display the full contents of the log and send you to the end of the file. You can always use your scroll wheel to browse through the buffer of your terminal window (if applicable). Instead, you’ll want to pipe the output of dmesg to the less command like so:

The above command will print out the contents of dmesg and allow you to scroll through the output just as you did viewing a standard log with the less command.

Viewing logs with tail

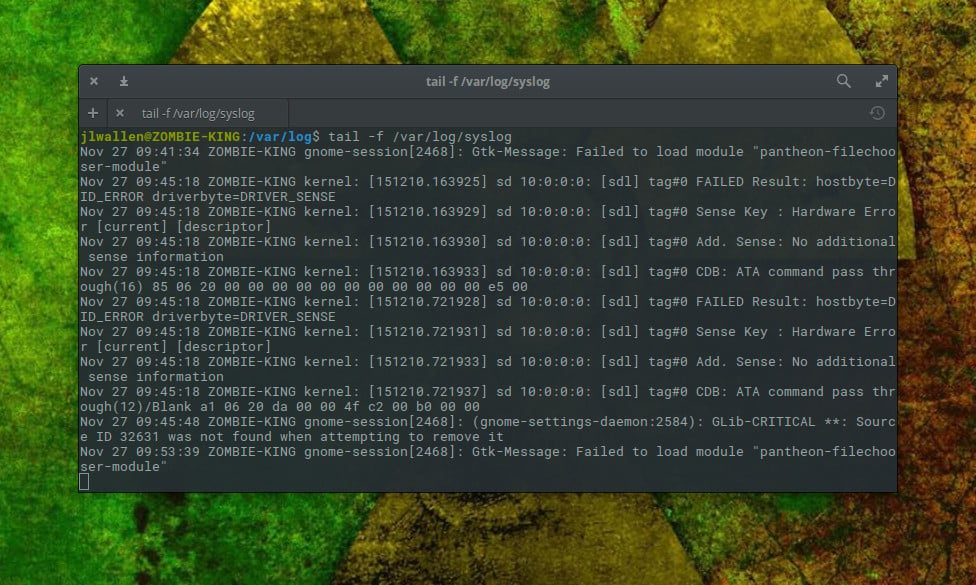

The tail command is probably one of the single most handy tools you have at your disposal for the viewing of log files. What tail does is output the last part of files. So, if you issue the command tail /var/log/syslog, it will print out only the last few lines of the syslog file.

But wait, the fun doesn’t end there. The tail command has a very important trick up its sleeve, by way of the -f option. When you issue the command tail -f /var/log/syslog, tail will continue watching the log file and print out the next line written to the file. This means you can follow what is written to syslog, as it happens, within your terminal window (Figure 3).

Using tail in this manner is invaluable for troubleshooting issues.

To escape the tail command (when following a file), hit the [Ctrl]+[x] combination.

You can also instruct tail to only follow a specific amount of lines. Say you only want to view the last five lines written to syslog; for that you could issue the command:

The above command would follow input to syslog and only print out the most recent five lines. As soon as a new line is written to syslog, it would remove the oldest from the top. This is a great way to make the process of following a log file even easier. I strongly recommend not using this to view anything less than four or five lines, as you’ll wind up getting input cut off and won’t get the full details of the entry.

There are other tools

You’ll find plenty of other commands (and even a few decent GUI tools) to enable the viewing of log files. Look to more, grep, head, cat, multitail, and System Log Viewer to aid you in your quest to troubleshooting systems via log files.

Advance your career with Linux system administration skills. Check out the Essentials of System Administration course from The Linux Foundation.