- What are the well-known UIDs?

- 4 Answers 4

- What does 1000 mean in chgrp and chown?

- 1 Answer 1

- Everything Important You Need to Know About UID in Linux

- What is UID in Linux?

- How to find the UID of a user in Linux?

- How to change UID of a user in Linux?

- How does UID associate with different system resources? [for advanced users]

- UID and files

- UID and processes

What are the well-known UIDs?

According to the useradd manpage, UIDs below 1000 are typically reserved for system accounts. I’m developing a service that will run as its own user. I know that well-known ports can be found in /etc/services . Is there a place where I can find out what well-known UIDs are out there? I would like to avoid crashing with someone else’s UID.

I thought it might be at first, but it’s not the sysadmin’s job to pick the UIDs of the programs he or she installs. It’s the developer’s (or package maintainer’s) job.

Actually, if the package developer mandates a specific UID or GID for their software (other than requiring root privileges), it is broken. For any value you choose, someone, somewhere, will be using your chosen UID (or GID) for something, and will be unwilling to change it to accommodate your software (and I don’t blame them).

This question appears to be off-topic for Stack Overflow as defined in the help center. It may be better suited to the Unix and Linux Stack Exchange site.

4 Answers 4

getpwent(3) iterates through the password database (usually /etc/passwd , but not necessarily; for example, the system may be in a NIS domain). Any UID known to the system should be represented there.

For demonstration, the following shell fragment and C code both should print all known UIDs on the system.

#include #include int main() < struct passwd *pw; while ((pw = getpwent())) printf("%d\n", pw->pw_uid); > UID 0 is always root and conventionally UID 65534 is nobody , but you shouldn’t count on that, nor anything else. What UIDs are in use varies by OS, distribution, and even system — for example, many system services on Gentoo allocate UIDs as they are installed. There is no central database of UIDs in use.

Also, /etc/login.defs defines what «system UIDs» are. On my desktop, it is configured so that UIDs 100-999 are treated as system accounts, and UIDS 1000-60000 are user accounts, but this can easily be changed.

If you are writing a service, I would suggest that the package installation be scripted to allocate a UID as needed, and that your software be configurable to use any UID/username.

Could you either edit this to mention your comment on Bane’s answer above or log that as a new answer? That seems to be the real answer to my question — that the system UIDs are not common across unix/linux distributions, so the problem cannot be solved. I’d like to accept that as the answer.

I know this is an old post, but since I am here in 2017, still trying to answer a similar question I thought this additional information was relevant for anyone else in the same position.

The concept of «Well known UIDs» stems back to the early days of unix, before there were multitudes of distributions and unix variants. «Well known» UIDs were considered to be those for system users like adm, daemon, lp, sync, operator, news, mail etc, and were standard across all the various systems in order to avoid uid clashes. These users are still present in modern unix-like operating systems.

Standardising uid’s across an organisation is the key to avoiding these problems. As was pointed out in a comment above, these days any uid you choose is likely to be in use ‘somewhere’, so the best a sysadmin can aim for is to ensure that uid’s are standard across all the systems that they maintain, then allocating a new uid for an application becomes simple.

To that end, for many years I have found the post linked below invaluable, and sadly there are not a lot of similar posts on the topic, and what’s out there is hard to find.

If you search that blog under the ‘uid’ tag there are other relevant posts, including a script to automate the process of standardising uid’s across multiple hosts under Linux.

This User ID Definition is also an invaluable resource.

The short answer is, that it doesn’t really matter which uid’s you use, as long as they are unique and standard across your organisation, to avoid clashes.

What does 1000 mean in chgrp and chown?

I am reading a blog to integrate EFK(a log system) into k8s in centos 7.4. There are following instructions:

# mkdir ~/es_data # chmod g+rwx es_data # chgrp 1000 es_data # chown 1000 -R es_data # ls -l /root/es_data/ total 8 drwxrwxr-x 2 1000 1000 4096 Jun 8 09:50 ./ drwx------ 8 root root 4096 Jun 8 09:50 ../ I log in as root. The instructions say, If I do chgrp 1000 es_data and chown 1000 -R es_data, the director’s owner and group would be 1000. But when I follow the instructions: I see following:

drwxr-xr-x. 2 master16g master16g 6 Jul 11 15:27 es_data The owner and group appears to machine hostname, master16g . Could someone drop me hints what happens here for chgrp 1000 and chown 1000 ?

First of all, nobody other then you knows what that instruction is. however, i think this is about ES docker image. If you run official ES docker image — you’ll see, that elasticsearch UID is 1000 and elasticsearch GID is also 1000

1 Answer 1

chown changes the owner, chgrp changes the group. Because you have user and group both named master16g having 1000 as UID and GID respectively, this is why you see the user name and the group name on the list. chown accepts UID as parameter as well as username, this is well documented in the manual. chgrp also accepts GID and group name. You can change both also with one command chown 1000:1000 es_data -R or chown master16g:master16g es_data -R .

First Linux user has usually UID/GID 1000.

For instance, if you chown 0:1000 file you will see root:master16g as the file owner.

You can get the details of the elasticsearch user by running id elasticsearch .

But what’s the purpose why instruction ask us to change owner and group both to 1000, or first linux user? But the screen show numerical 1000.

Those are Linux basics. Without changing the permissions your user won’t be available to do any changes on the given directory or underlying files. Not sure why did you put those file on /root though.

EFK is supposed to run as user elasticsearch, and normally user elasticsearch has uid/gid of 1000/1000, that’s why the instruction. But in your container another user, master16g , occupied this id, that confused you.

Everything Important You Need to Know About UID in Linux

This Linux Basics guide teaches you everything important associated with UID in Linux.

What is UID in Linux?

UID stands for user identifier. A UID is a number assigned to each Linux user. It is the user’s representation in the Linux kernel. The UID is used for identifying the user within the system and for determining which system resources the user can access. This is why the user ID should be unique.

You can find UID stored in the /etc/passwd file. This is the same file that can be used to list all the users in a Linux system.

Use a Linux command to view text file and you’ll see various information about the users present on your system.

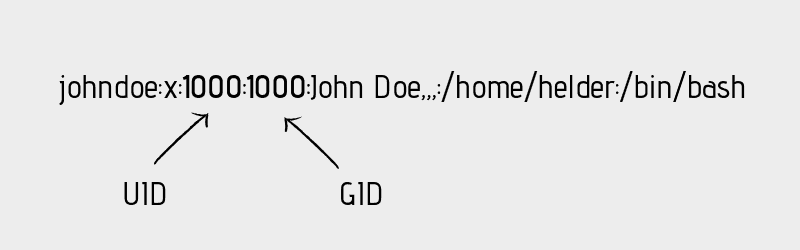

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync games:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologin man:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/usr/sbin/nologin lp:x:7:7:lp:/var/spool/lpd:/usr/sbin/nologin mail:x:8:8:mail:/var/mail:/usr/sbin/nologin news:x:9:9:news:/var/spool/news:/usr/sbin/nologin johndoe:x:1000:1000:John Doe. /home/helder:/bin/bash davmail:x:127:65534::/var/lib/davmail:/usr/sbin/nologin statd:x:128:65534::/var/lib/nfs:/usr/sbin/nologinThe third field here represents the user ID or UID.

Do note that in most Linux distributions, UID 1-500 are usually reserved for system users. In Ubuntu and Fedora, UID for new users start from 1000.

For example, if you use adduser or useradd command to create a new user, it will get the next available number after 1000 as its UID.

How to find the UID of a user in Linux?

You can always rely on the /etc/passwd file to get the UID of a user. That’s not the only way to get the UID information in Linux.

The id command in Linux will display the UID, GID and groups your current user belongs to:

id uid=1000(abhishek) gid=1000(abhishek) groups=1000(abhishek),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin),126(sambashare),127(kvm)You can also specify the user names with the id command to get the UID of any Linux user:

id standard uid=1001(standard) gid=1001(standard) groups=1001(standard)How to change UID of a user in Linux?

Suppose you had several users on your Linux system. You had to delete a user because he/she left the organization. Now you want its UID to be taken by another user already on the system.

You can change the UID by modifying the user using usermod command like this:

You need to have superuser privilege to execute the above command.

Do you remember the file permission and ownership concept in Linux? The ownership of a file is determined by the UID of the owner user.

When you update the UID of a user, what happens to the files owned by this user?While all the files in the home directory of user_2 will have their associated UID changed, you’ll have to manually update the associated UID of other files outside the home directory.

What you can do is manually update the ownership of the files associated with the old UID of the user_2.

find / -user old_uid_of_user_2 -exec chown -h user_2 <> \;How does UID associate with different system resources? [for advanced users]

UIDs are unique to one another and thus they can also be used to identify ownership of different system resources such as files and processes.

UID and files

I hope you are familiar with the file permission concept in Linux. When you’re creating a file, you’re the owner of this file. Now you can decide who gets to do what with this file. This is part of Linux’s DAC mechanism where each file is left at its owner’s discretion.

You can read a file’s ownership by using either ls or stat command. Let’s do it with the popular ls command and check the ownership of either the binary sleep or passwd .

As you can see, the file /usr/bin/sleep belongs to root:

ls -l $(which sleep) -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 39048 Mar 6 2020 /usr/bin/sleepLet’s force it to map the ownership with UID instead of username:

ls -lhn $(which sleep) -rwxr-xr-x 1 0 0 39K Mar 6 2020 /usr/bin/sleepHere’s fun information. Your operating system doesn’t understand «usernames». Whenever a program needs to work with usernames or needs to print such, it refers to the /etc/passwd file to extract the information.

You don’t have to take my words for it. See it yourself with strace program which prints all the system calls made by a program.

strace ls -lhn $(which sleep) 2>&1 | grep passwd What you are trying to see is whether ls command is trying to read the /etc/passwd file or not.

strace ls -lh $(which sleep) 2>&1 | grep passwd openat(AT_FDCWD, "/etc/passwd", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 6UID and processes

Processes have owners too, just like files. Only the owner (or the root user) of a process can send process signals to it. This is where the UID comes into play.

If a normal user tries to kill a process owned by another user, it will result in error:

kill 3708 bash: kill: (3708) - Operation not permittedOnly the owner of the process or the root can do this.

A process must be regulated. Regulated as in you need to have a way to limit or know how much a process is allowed to do. This is determined by its UID(s).

There are three types of UIDs associated with a process.

- Real UID: Real UID is the UID that a process adopts from its parent. In easier terms, whoever starts a process, the UID of that user is the real UID of the process. This is helpful in identifying who a process really belongs to. This is essential especially when the effective UID is not the same as the real UID which I’m going to talk about next.

- Effective UID: This is what mostly determines what permissions a certain process really has. While a user can start the process, it can run with a different user’s available permissions. The command passwd is one example of this. This program edits the file /etc/shadow , which is root owned. Therefore, a normal user shouldn’t be able to run this command or change his/her password. Luckily, the binary runs with an effective UID of 0 (i.e. root), which enables it to have enough privilege to edit the /etc/shadow file. Real and effective UIDs are mostly the same except in the case of SUID bit enabled binaries.

- Saved UID: UID that’s available at a process’s disposal. This one is not normally used, but is still there in case the process knows it’s not going to perform any privileged work, so it can change its effective UID to something that’s unprivileged. This reduces the surface of an unintentional misbehavior.

That’s it. I hope you have a better idea about UID in Linux now. Don’t hesitate to ask your questions, if any.

As a pro Linux user, if you think I missed some important concept about UID, please let me know in the comment section.