- Configuring your stable system

- Adding the repository

- Using Synaptic

- Using the command line

- Using backports

- Finding backports

- Installing backports on the command line

- Reporting bugs

- Migrate from backports.org to backports.debian.org

- List installed backports

- External links

- What is backporting, and how does it apply to RHEL and other Red Hat products?

- Why are versions important?

- Understanding versions in RHEL

- How backporting works

- Putting it all together in a real-life scenario

Configuring your stable system

In the following example, we will use bookworm as the current codename for Debian Stable. Please adjust the codename accordingly if you are using a different version of Debian.

If you’re setting up backports for a system that isn’t running the latest version of Debian (e.g. a bullseye system while the latest is bookworm) then you may also want to add a line for the «sloppy» backports section. Currently that is bullseye-backports-sloppy, but after the release of trixie, you’ll want to add a line for bookworm-backports-sloppy. Be warned, sloppy backports ruin the upgrade path between versions, but will contain newer versions of packages than in the regular backports.

Adding the repository

Using Synaptic

- In the following dialog box, select the tab «Third-Party Software» and click on the «Add. » button in the lower left corner:

deb http://deb.debian.org/debian bookworm-backports main contrib non-free

- Finally, hit the «Reload» button in Synaptic’s main panel to update the repository information on your system.

Using the command line

As root, or using sudo, open your sources.list file (Nano is the recommended editor for new users):

Append the following line to the bottom of the file:

deb http://deb.debian.org/debian bookworm-backports main contrib non-free

If you are a free software enthusiast, you might want to remove the contrib and non-free sections. (See Debian package management for details.)

Now that you have added the repository, update APT’s cache to include the backports in the list of available packages:

Using backports

Finding backports

There are a several different ways to find out if a backport of a certain Debian package exists. A pretty convenient one is using Debian’s web-based package search (packages.debian.org).

Backported versions of packages will also appear when searching their names with the apt search command, or one can view all available versions of a package by running:

Replacing package-name with the name of the package you wish to view.

Installing backports on the command line

The backports repository is low-priority by default. So, if you want to install a backported package, you will have to state that explicitly.

# apt install cockpit/bookworm-backports

This will attempt to install Cockpit from bookworm-backports, preferring dependencies from stable. Sometimes backports depend on other backports, and it is necessary to specify these dependencies aswell.

(Dependency is just a stand in for a theoretical backport dependency)

# apt install cockpit/bookworm-backports dependency/bookworm-backports

Another option is to use the -t target release flag, but this can sometimes lead to unnecessarily downloading dependencies from backports.

# apt -t bookworm-backports install cockpit

The -t option here specifies bookworm-backports as the target release. This would install a newer version of Cockpit and all its reverse dependencies from bookworm-backports instead of the older one from Debian stable release.

Reporting bugs

Because of limitations in the Debian Bug Tracking System, any bugs relevant to backported packages still have to be reported to the debian-backports list.

Migrate from backports.org to backports.debian.org

On Sept. 5th, 2010, Backports became an official service (see announcement).

- replace backports.org with http://deb.debian.org/debian in /etc/apt/sources.list*.

- run apt update

- remove the backports.org key from your keyring. Depending how you installed it.

- apt purge debian-backports-keyring

or - apt-key del 16BA136C

- apt purge debian-backports-keyring

List installed backports

Out of all installed packages, which ones are backports? One way to tell is by version: all backports are tagged with ~bpo, for example, 24.5+1-6~bpo8+1, so at the command line you might say:

External links

- backports.debian.org for more information

- Article about backports on cliss21.com: The article contains information on how to backport packages as well as some step-by-step simple examples to start with.

- Diffs between bullseye-backports and bookworm: A useful comparison of package versions in bullseye-backports and bookworm.

What is backporting, and how does it apply to RHEL and other Red Hat products?

Version numbers are important, but aren’t always what they seem at first glance. Red Hat, for example, often backports updates to the software we ship in Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) to maintain the version that we shipped.

This is a post to follow to Jean-Sébastien Tougne’s post on finding the latest available kernel. Jean-Sébastien’s article was responding to a question on the Red Hat Learning Community, where the poster was seeking the latest version of the kernel for Red Hat Enterprise Linux. That prompted me to write an article that went deeper into the nuance and strategy the Red Hat Enterprise Linux team employs for this to be magically delicious for administrators.

Why are versions important?

The first question is: why are versions important? In some cases that is very straightforward, newer software means new features and new capabilities. For example, RHEL 8 updated established subsystems like systemd and added new features like Application Streams, Image Builder, and more.

Sometimes what comes with a new version is less dramatic, like when we released RHEL 8.1. The new stuff from RHEL 8 was still there, but we added a System Role for managing local storage and newer versions of software packages delivered through the Application Streams mechanism like NGINX 1.16.

Then we get down to the most tedious and detailed answer to the question of why versions are important? Software has bugs. They range in severity, scope, and exploitability. Users request new features or changes to packages. Closing of these bugs and requests is also reflected in updated versions of packages that are provided as part of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux distribution.

Where would one go to find all this information? There is not a single answer to that question in terms of what is new in a major release. Red Hat’s product marketing teams do a lot of work getting this information out there. Be it through updates to redhat.com product pages, blogs, talks at conferences like Red Hat Summit or other industry shows, and through materials for customer-facing employees and partners. Likewise, the next level of detail, the Engineering and documentation teams at Red Hat produce release notes like this one for Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8.1.That final level of detail, bugs, vulnerabilities, etc. is what the rest of this article is going to address.

Understanding versions in RHEL

Before we dive into the details of what’s been applied to this or that version of software distributed with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, let us first discuss how the software distributed with Red Hat Enterprise Linux is maintained. We refer to some of this process as backporting, but what is it and how does it happen?

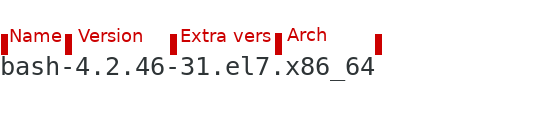

If you look at an RPM package distributed with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, you will notice a consistent naming convention. As an example, take a look at the Bash shell package. To get this information, you could run yum list bash or, in the example below, I used

Name: Name of the software. In this case, the Bash shell.

Version: The version of the open source project used to make this package. In this example, this package is based on version 4.2.46 from the GNU Project, the maintainers of Bash.

Extra vers[ion]: This portion of the version on this package is Red Hat specific. Generally, RPM provides this field for the packager of the software to maintain their own version specific data. Because this package comes from Red Hat, this extra version data is being applied by the Red Hat maintainer of this RPM. Different maintainers or teams at Red Hat may choose to format this field slightly differently, but it has some versioning information and usually indicates the version of Red Hat Enterprise Linux that the package was made for.

Arch[itechure]: The CPU type the binaries contained in this package are compiled for. You could see other CPU architectures in this field if the package binaries were compiled for a different CPU (e.g. aarch64 ), or noarch, which would indicate that the package is architecture neutral.

How backporting works

Now we are digging into more details, what did Red Hat do to make 31.el7 and how that is different than earlier versions of the bash-4.2.46 RPM package? What we are talking about now is backporting. Literally, we are taking code from a newer version upstream and integrating it back to an older version of the software. This is one of the great things about open source.

When Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, the version running on the example machine I am using, was branched from Fedora upstream, Red Hat engineers pulled the source for Bash 4.2.46 from Fedora’s package. The Red Hat engineers continue to maintain this copy of source code distributed with Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7.

As changes are made upstream to fix bugs or address vulnerabilities, Red Hat’s engineers may take the changes from upstream and integrate them to update the version shipped with RHEL 7. Not all changes are backported, of course. We are strictly looking to address bugs and security issues, rather than trying to bring new features to older releases.

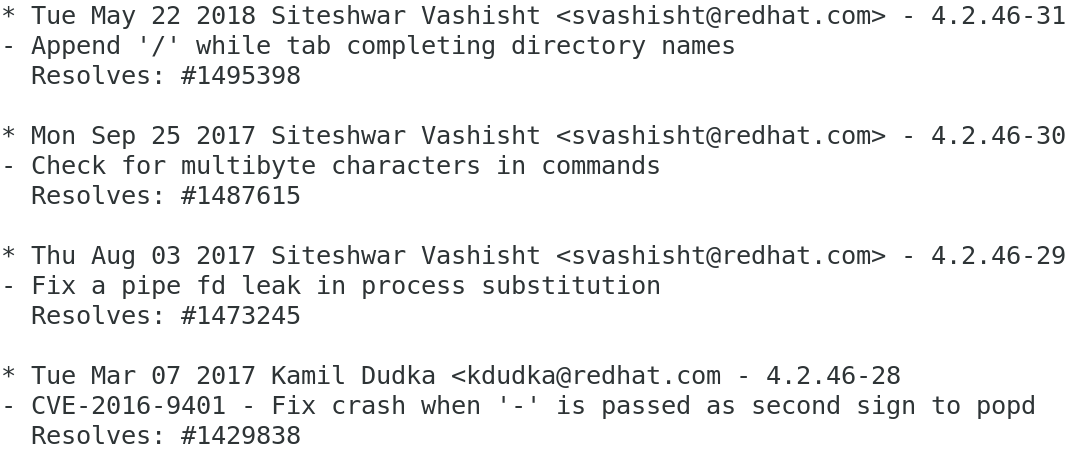

What does this look like to the people administering a machine? If you take a look at the changelog of a package, in our case bash , using rpm -q —changelog bash you would see something like the following, note that this log is formatted newest change to oldest, so you may want to pipe the output to less to see the newest changes:

From this output, we can see the history of the package as well as what was changed in each of the versions of the RPM that were issued. The most recent change is the one that generated version 4.2.46-31.

In addition to the description of what this update resolves, readers are also given the Red Hat bugzilla ID number ( #1495398) that corresponds to this, now resolved, problem. Alternatively, down in the update that resulted in version 4.2.46-28, a security vulnerability was addressed (CVE-2016-9401). If the short resolution details here in the changelog are insufficient for what you need to know about this update, you can access these additional resources to find more in-depth information.

Why would Red Hat choose to operate RHEL packaging this way? Why go through all the effort of backporting instead of just downloading updated source from the open source project and compiling a new version?

Red Hat Enterprise Linux is a complex distribution with a lot of different packages that make up the product. Further, on top of this platform many organizations run their own workloads and software (which has their own complexities). If Red Hat replaced Bash with a completely new version, would this change affect any of those other packages or workloads running on top of the distribution?

New releases of Bash may have removed or changed the way some features (like, say, POSIX-related behavior) that could affect scripts or software running on top of RHEL. That’s fine for the upstream release or future versions of RHEL when users are expecting it, but bad for a release that customers expect to be stable between updates.

By using this method of backporting, Red Hat is able to provide updates to the operating system, but reduce risk historically associated with applying updates to complex operations infrastructure.

Putting it all together in a real-life scenario

A number of organizations have security requirements that mandate system updates be applied within a certain number of days or months. In order to measure the success of compliance with these policies, systems can be audited with security scanners.

However, most scanning software we’ve encountered does not account for the backporting of features that Red Hat uses for maintaining and updating packages in the Red Hat Enterprise Linux distribution. As an example, connecting to the SSH daemon running on my Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 system shows a version of:

However, the most recent version of OpenSSH from openssh.com is 8.1, not the 7.4 being reported from the system.

The likely outcome would be me getting a notification from the auditor telling me that I need to update the ssh package on my system. However, this is likely not needed since I have the latest, supported package from Red Hat installed on the machine. While my machine is reporting openssh 7.4, it’s also showing an extra version of 21.el7, and if needed, I can pull data from the RPM changelog to check that vulnerabilities that the auditor may be concerned about have been closed through backported fixes.

I hope you can use this knowledge of how Red Hat maintains Red Hat Enterprise Linux software through the practice of backporting, along with the sources of information about releases and command-line tools to get even more depth about specific changes in your career and organization.