From Open Wi-Fi to WPA3

Security in Wi-Fi networks has been, at some point non-existent, then questioned, improved and questioned again over the last two decades.

The Wi-Fi certification is a certification program which is backed by the standards developed from the 802.11 IEEE Working Group. Wi-Fi certifications are issued by the Wi-Fi Alliance to devices that comply to one of their certifications, WPA2 [1] for example.

Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) was the first certification, testing devices for Wi-Fi security. According to IEEE [2] it was introduced in 1997. Following the published attacks on WEP [3] the certification got quickly replaced with a more secure version, WPA. WPA was only an intermediate change and got superseded by WPA2 in 2004, only one year after its introduction in 2003.

There are many tutorials about “cracking wifi” available on the internet. Most of those cover the aircrack-ng suite and show how to de-authenticate a client which is connected to a Wi-Fi network in preparation of later cracking the hopefully weak Pre-Shared-Key (PSK).

Those tutorials are mostly geared towards SOHO networks, which may have a valid point in attacking the Wi-Fi network at the weakest link, the password.

Even with the latest and patched firmware the security of WPA2-Personal networks heavily rely on the chosen PSK. Those attacks are well known for years, to mitigate those weaknesses the Wi-Fi alliance introduced WPA3.

How is WPA working?

Personal

WPA2-Personal uses a PSK in order to authenticate with the Wi-Fi network.

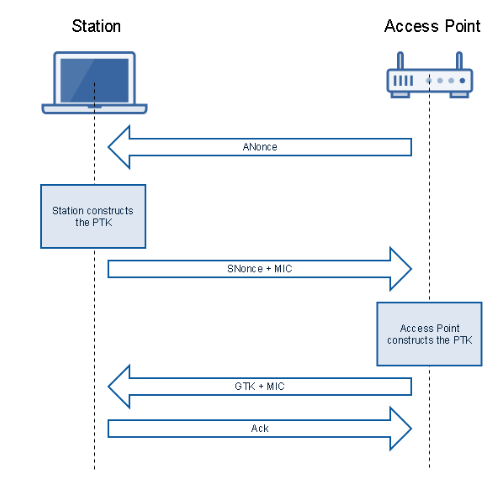

From the PSK a Pairwise Transient Key (PTK) is generated which is used to encrypt the traffic. The PTK is generated in the four-way handshake which is done between the client (station) and the Access Point.

The four-way handshake looks like this:

There is also a standard for corporate environments which is called WPA-Enterprise. While it is based on the same principals as the personal Wi-Fi a much broader range of possible authentication methods is available.

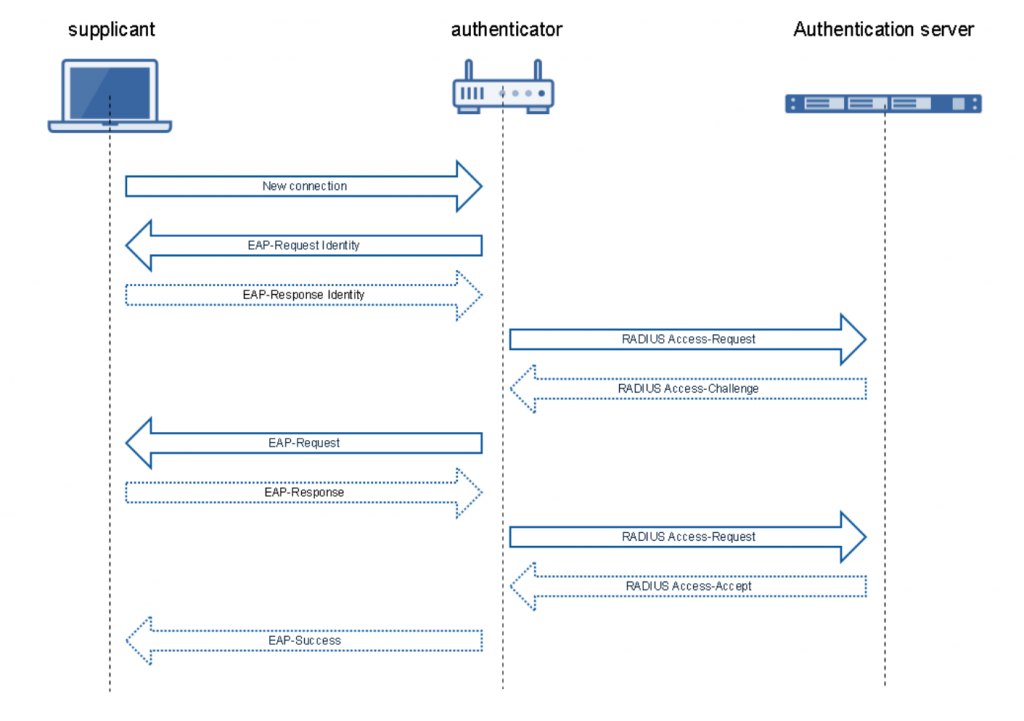

The main difference is that the supplicant (client) does not authenticate with the Access Point directly but rather with an authentication server which is in most cases a radius server. That allows to manage users in a central database.

The authentication method which provides the best security level is EAP-TLS it is based on x.509 certificates for authentication. There are further methods which are all grouped as Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP) methods.

The AP is acting as the network access server or authenticator:

3. Radius Authentication in WPA2-Enterprise

What is WPA3 changing?

First of all, WPA3 is considered a game changer when it comes to personal wireless networks. The changes to enterprise Wi-Fi networks are less of a big deal and can be recapitulated in one sentence.

WPA3-Enterprise has mandated the use of Management Frame Protection and optionally uses the NSA-Suite-B 192 [4] bit security level.

"The 192-bit security level corresponds to an elliptic curve size of 384 bits and AES-256; it also makes use of SHA-384." RFC 5430

What are the changes, that make WPA3 a game changer in WPA3-Personal Networks? The short answer is, the authentication is much stronger and should resist common attacks against the PSK.

With WPA2 the PMK used during the four-way handshake is derived directly from the PSK. This allowed an attacker who sniffed the four-way handshake, to crack the password with an offline password attack.

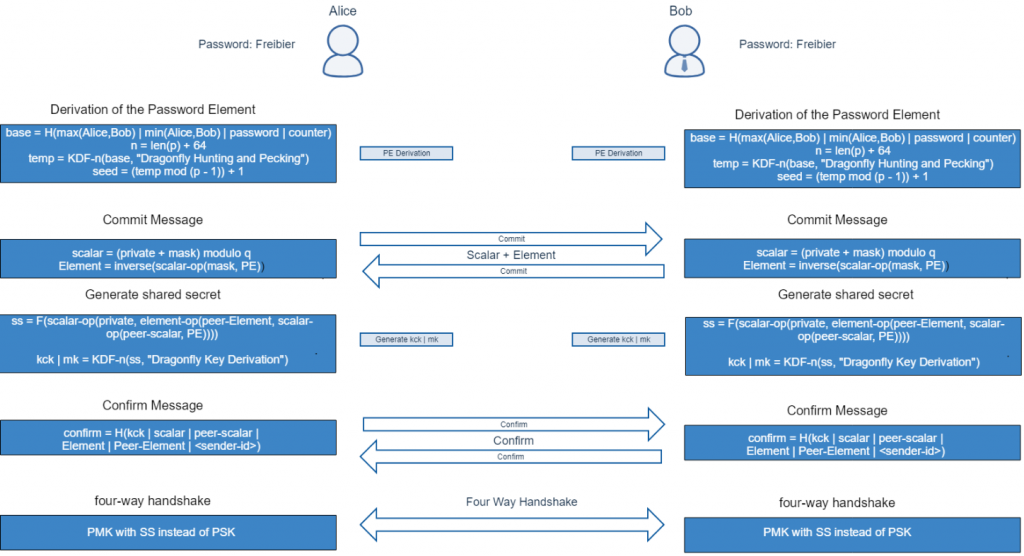

In WPA3, the client does authenticate with a new protocol called Simultaneous Authentication of Equals (SAE)[5]. The PMK is now derived from a Password Element (PE) which is the result of a successful authentication with SAE. During the authentication with SAE the password will never be transferred over the air.

The resulting PMK, which is used in the four-way handshake, should be cryptographically strong enough to resist offline cracking attacks.

Furthermore, WPA3-Personal makes use of Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS). Therefore even if a malefactor is in possession of the password it would not be possible to decrypt the traffic.

Is it really more secure then WPA2?

In theory, Simultaneous Authentication of Equals sounds like a major update to WiFi security compared to WPA2.

It appears great to us as users, that the WiFi will be secure even if one only configures a short passphrase which would be cracked in a matter of days with a captured WPA2 handshake.

Practically, it will take a lot of time until all WiFi Networks and clients support the new protocols.

Cryptographic Vulnerabilities

Recently, there where the first cracks in the shiny WPA3 security surface. A research group around Mathy Vanhoef published a paper called Dragonblood [6], where they describe a couple of attacks which for example, allow an attacker to brute-force the PSK with an offline attack.

The attacks described in the paper where, introduced to the public through coordinated disclosure. Therefore, most vendors will have fixed the implementations even before WPA3 capable routers and clients are being released.

However, the risk for downgrade attacks due to backward compatibility with WPA2 may remain.

Network Attacks

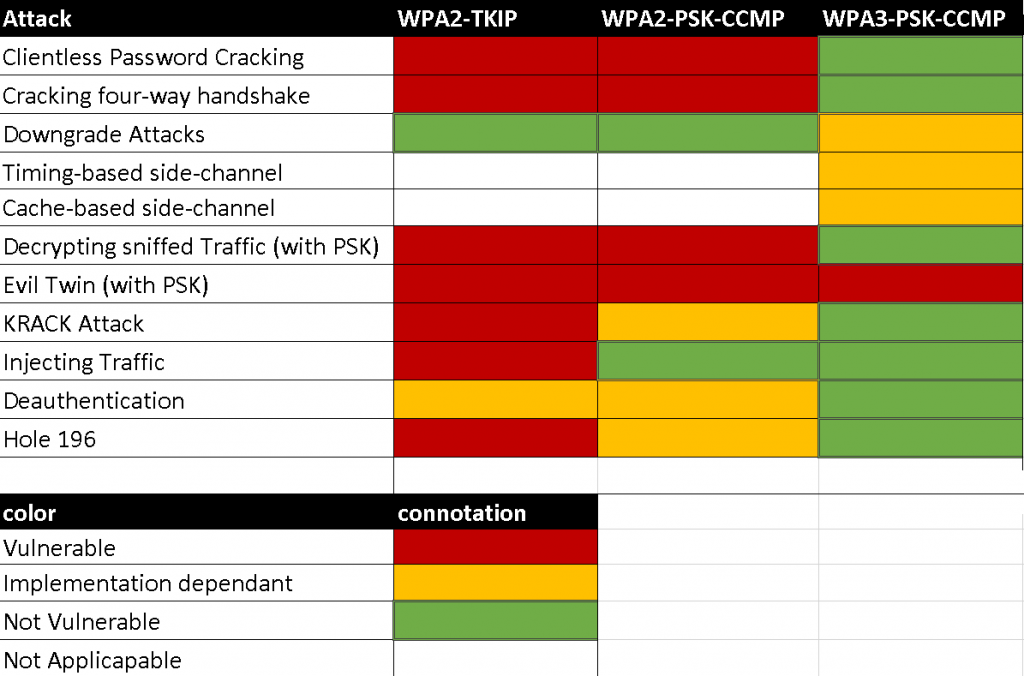

The classical attacks like decryption[6] of traffic and injection[7] of packets are not possible anymore, as they are effectively mitigated with PFS and the introduction of AES in WPA2.

There is an attack against Wi-Fi networks called the Evil Twin Attack[8] which requires some user interaction but will still work with WPA3.

The theory of it is simple: Everything a malefactor needs to know to clone an AP is the SSID, authentication scheme and the authentication token – in this case the PSK. Knowing the PSK is the biggest obstacle on carrying out this attack. A successful Evil Twin attack brings the malefactor in a Man-in-the-Middle (MiTM) position without the need of exploiting something as the user is already connected to the malicious network. Once the MiTM position has been acquired, it is possible to sniff and modify un-encrypted traffic like HTTP, FTP and other un-encrypted protocols. Unfortunately there is no technical mitigation to this.

The following table gives a quick overview of some well known attacks against personal networks and which standard is vulnerable:

Conclusion

With the precondition, that vendors fix the vulnerabilities published in the Dragonblood research paper, WPA3 is a real improvement to the security of wireless networks for WPA3-Personal networks.

The changes in WPA3-Enterprise are minimal, as WPA2-Enterprise already provides sufficiently strong authentication methods (EAP-TLS)

and did not need to be hardened as much as WPA2-Personal had to.

Some general but fundamental factors may weaken the security of enterprise Networks:

- misconfigurations

- bad design decisions

- legacy hardware

- legacy software

Those factors still allow the introduction of weaknesses in enterprise networks and should be carefully evaluated.

Overall the improvements introduced by WPA3 are significant for WPA3-Personal. Considered that many hardenings, like Management Frame Protections, were already backported in the WPA2 standard. All in all Wi-Fi security[10] has really moved a big step forward.

Citations and Sources:

- IEEE Standards association, https://standards.ieee.org/standard/802_11i-2004.html (2004)

- IEEE Standards association, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/654749?arnumber=654749&isnumber=14251&punumber=5258&k2dockey=654749@ieeestds&query=(802.11%201997)%3Cin%3Emetadata&pos=0 (1997)

- IEEE Standards association, https://standards.ieee.org/standard/802_11i-2004.html (2004)

- Reclassification of Suite B Documents to Historic Status R. Housley, https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8423 (2018)

- Dragonfly Key Exchange D. Harkins, Ed., https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7664 (2015)

- Dragonblood – Analysing WPA3’s Dragonfly Handshake, Mathy Vanhoef et al. and Eyal Ronen et al., https://wpa3.mathyvanhoef.com/ (2019)

- https://wiki.wireshark.org/HowToDecrypt802.11

- Release the Kraken: New KRACKs in the 802.11 Standard, Mathy Vanhoef et al. and Frank Piessens et al., https://www.krackattacks.com/ (2017)

- http://solstice.sh/python/wireless/2015/11/01/python-evil-twin/

- https://www.wi-fi.org/discover-wi-fi/security

How to secure an open wifi access point

A public access point is public. This means that anybody can connect to it and use it. Thus, «protecting the access point against malicious users» is not a well-defined goal. The access point has no secret data to keep confidential, or a restricted service to offer only to authorized users. It is public.

What you might want is to protect users from each other: you don’t want one user of the public access point to be able to eavesdrop on other users, or alter their data, or even simply disrupting communications. This is a problematic of big sites which really want to provide «free WiFi» for a lot of people but have a recurrent problem of antisocial users.

It turns out that you cannot. The cryptographic elements in the WiFi protocol are meant to:

- Enforce authentication, keeping people out of the connection if the access point is not public, but requires authentication.

- Prevent eavesdropping on the connection of duly connected users from people who are not connected.

However, nothing in the WiFi protocol was designed to prevent two connected users from spying on each other. With a public WiFi, everybody can connect (by definition), so everybody can spy on everybody.

Crippling your access point, e.g. by blocking port 443, won’t bring any security, except in the following sense: if the access point is made unusable because of too strict restrictions, then people won’t use it, and thus the spying issue disappears: there is no attacked user if there is no user at all. But for the remaining users, blocking port 443 just makes their situation worse: not only does it not prevent other users from spying on their traffic, but it also prevents them from defending themselves by using HTTPS browsing when possible.

You seem to be aware that «legal sources» may ask for logs. The legal situation is actually worse (for you):

- By willingly running an open access point, you have become a service provider, so you are bound by all the regulations attached to that state. The ARCEP could give you the relevant information, but be warned that this goes much beyond simple squid logs.

- Your own Internet access was provided to you based on a contract which explicitly forbids sharing beyond «home usage». If you act as a service provider (that’s what you are trying to do), then you are in clear violation of the terms of that contract, and your ISP may lawfully shut your access down.

- If someone uses your access point to then engage in «illegal activities» (e.g. attacking other sites) then you could be considered as accomplice. That’s the point of the ARCEP regulations: registered service providers can claim exemption, in the way that phone companies do not get into legal trouble when criminals plot crime by phoning each other. This exemption is not automatically granted to just any random citizen who plugs a WiFi access point.

Therefore, running your own public access point, just like that, really is a bad idea, however generous the basic principle might seem at first look.