- How to change the hostname of a RHEL-based distro?

- 3 Answers 3

- How to configure a hostname on a Linux system

- Configure a static hostname

- Configure a persistent hostname

- Training & certification

- Wrap up

- How to change the identity of a Linux system

- Automation advice

- Great Linux resources

- How to change your hostname in Linux

- Great Linux resources

- Background

- Working with hostnames

- GNOME tip

- Wrapping up

How to change the hostname of a RHEL-based distro?

I logged in for the first time, opened terminal, and typed in ‘hostname’. It returned ‘localhost.localdomain.com’. Then I logged as the root user in terminal using the command, ‘su –‘, provided the password for the root user and used the command ‘hostname etest’ where etest is the hostname I’d like my machine to have. To test if I got my hostname changed correctly, I typed ‘hostname’ again at terminal and it returned etest. However, when I restart my machine, the hostname reverts back to ‘localhost.localdomain.com’. Here are the entire series of commands I used in terminal.

[thomasm@localhost ~]$ hostname localhost.localdomain [thomasm@localhost ~]$ su - Password: [root@localhost ~]# hostname etest [root@localhost ~]# hostname etest 3 Answers 3

On RHEL and derivatives like CentOS, you need to edit two files to change the hostname.

The system sets its hostname at bootup based on the HOSTNAME line in /etc/sysconfig/network . The nano text editor is installed by default on RHEL and its derivatives, and its usage is self-evident:

You also have to change the name in the /etc/hosts file. If you do not, certain commands will suddenly start taking longer to run. They are trying to find the local host IP from the hostname, and without an entry in /etc/hosts , it has to go through the full network name lookup process before it can move on. Depending on your DNS setup, this can mean delays of a minute or so!

Having changed those two files, you can either run the hostname command to change the run-time copy of the hostname (which again, was set from /etc/sysconfig/network ) or just reboot.

Ubuntu differs in that the static copy of the hostname is stored in /etc/hostname . For that matter, many aspects of network configuration are stored in different places and with different file formats on Ubuntu as compared to RHEL.

How to configure a hostname on a Linux system

Make it easier to access your Linux computer by giving it a human-friendly name that’s simpler to use than an IP address.

Each person has a unique identity, such as their name and birth date. Computers also have individual identities, specifically, their hostnames and internet protocol (IP) addresses. Each machine has a valid IP address, but referring to a system by its IP address is not practical.

Instead, you can configure a computer’s hostname, which is the machine’s human-friendly name. You can map the hostname to the IP address so that it’s easy to connect to a machine using its name.

Configure a static hostname

Display the system’s hostname using:

You can also use the hostname command to modify the system’s name temporarily. Here’s an example:

This change is only temporary. After a reboot, all changes will revert.

Configure a persistent hostname

To persistently change the hostname, use the hostnamectl command, or directly modify the default configuration file /etc/hostname .

Here’s an example of modifying the hostname permanently using the hostnamectl command. This shows the change:

$ hostnamectl set-hostname server1.example.comTraining & certification

After executing this command, don’t forget to verify the change using the hostname command.

You can confirm this entry by displaying the /etc/hostname file contents.

Wrap up

These examples show you how to configure the hostname for your machine. Note that during the configuration steps, your system will not automatically resolve the hostname with the IP address. This article covers only how to configure the hostname for a machine.

How to change the identity of a Linux system

I’d like to show you a magic trick. Go to your favorite shell prompt, and type:

[skipworthy@showme ~]$ hostname showmeAutomation advice

The hostname command is provided in Linux to query «who» the computer thinks it is. How did that happen? How does my computer know what it’s called? I show you how the trick is done in a bit, but first, let me show you another one:

[root@showme skipworthy]# hostnamectl set-hostname spot [root@showme skipworthy]# hostname spotThanks once again to systemd (which is implemented in most but not all modern GNU/Linux distributions, including Red Hat-based systems) changing the name of your Linux computer is pretty easy. (By the way, the name in the prompt will change with the next login.) I’ve discussed how DNS allows us to identify a computer on the network by mapping a name to an IP address. This is on the other side of that. Here you’re looking at how the machine identifies itself, which is important for making things like authentication work properly if the computer is part of a domain.

After the hardware is enumerated and drivers have been loaded at bootup, on a systemd-based distribution, the bootloader loads and runs the systemd scripts. Near the beginning of this process is when the hostname is set:

2.653601] rtc_cmos 00:00: setting system clock to 2020-11-17 19:36:44 UTC ( 1605641804) [ 2.654885] Freeing unused kernel memory: 1980k freed [ 2.655179] Write protecting the kernel read-only data: 12288k [ 2.657125] Freeing unused kernel memory: 416k freed [ 2.658710] Freeing unused kernel memory: 552k freed [ 2.663220] random: systemd: uninitialized urandom read (16 bytes read) [ 2.663530] random: systemd: uninitialized urandom read (16 bytes read) [ 2.663543] random: systemd: uninitialized urandom read (16 bytes read) [ 2.667147] systemd[1]: systemd 219 running in system mode. (+PAM +AUDIT +SEL INUX +IMA -APPARMOR +SMACK +SYSVINIT +UTMP +LIBCRYPTSETUP +GCRYPT +GNUTLS +ACL + XZ +LZ4 -SECCOMP +BLKID +ELFUTILS +KMOD +IDN) [ 2.667189] systemd[1]: Detected virtualization kvm. [ 2.667200] systemd[1]: Detected architecture x86-64. [ 2.667204] systemd[1]: Running in initial RAM disk. [ 2.667250] systemd[1]: Set hostname to . [ 2.701020] random: systemd: uninitialized urandom read (16 bytes read) Apart from that, in systems where systemd is not managing the user-space, you can configure the hostname in a couple of files. These files are actually where systemd looks for this info and records it when you use the hostnamectl command. The hostname and hostnamectl commands actually use kernel-level system calls named gethostname , getdomainname , and some functions provided by the resolver system call. These have been around since pretty early on in the history of the Linux kernel. These are the same system calls used by the shell to populate the machine’s name in the prompt, among other places.

Both of the files you’re going to look at reside in /etc , which you’ll recall is the default location for most of the files used to configure and manage a Linux system. The first one is called, appropriately, /etc/hostname :

[root@showme skipworthy]# cat /etc/hostname showmePretty simple: When you invoke hostname from the shell prompt, Linux looks at the /etc/hostname file for the answer. You can also use the hostname command to change the computer name, but in systemd-managed kernels, it’s generally preferred to use the hostnamectl command instead.

The other file is /etc/hosts , which is where Linux looks to translate IP addresses to names before it checks /etc/resolv.conf for DNS info. Here is the /etc/hosts file:

[skipworthy@showme ~]$ cat /etc/hosts 127.0.0.1 showme.forest showme 192.168.11.111 showme.forest showme 192.168.0.200 Jupiter 192.168.0.100 uhuraThe first couple of lines are what you want to look at. Note the format is:

Great Linux resources

So you have the IP address, then the hostname.domainname (or Fully Qualified Domain Name), followed by the hostname. You can also add aliases or additional domain aliases if they are used in the environment.

Use the -f switch when you invoke the hostname command to see the FQDN of your host:

[skipworthy@showme ~]$ hostname -f showme.forestThe hostnamectl command has some other interesting and useful switches and flags: You can set the environment type (development vs. production, for example), and you can even put location notes (rack 3, room 200, for example). You can query and set these remotely. As usual, you can learn all kinds of cool things from the good ol’ man pages.

How to change your hostname in Linux

What’s in a name, you ask? Everything. It’s how other systems, services, and users «see» your system.

Great Linux resources

Your hostname is a vital piece of system information that you need to keep track of as a system administrator. Hostnames are the designations by which we separate systems into easily recognizable assets. This information is especially important to make a note of when working on a remotely managed system. I have experienced multiple instances of companies changing the hostnames or IPs of storage servers and then wondering why their data replication broke. There are many ways to change your hostname in Linux; however, in this article, I’ll focus on changing your name as viewed by the network (specifically in Red Hat Enterprise Linux and Fedora).

Background

A quick bit of background. Before the invention of DNS, your computer’s hostname was managed through the HOSTS file located at /etc/hosts . Anytime that a new computer was connected to your local network, all other computers on the network needed to add the new machine into the /etc/hosts file in order to communicate over the network. As this method did not scale with the transition into the world wide web era, DNS was a clear way forward. With DNS configured, your systems are smart enough to translate unique IPs into hostnames and back again, ensuring that there is little confusion in web communications.

Modern Linux systems have three different types of hostnames configured. To minimize confusion, I list them here and provide basic information on each as well as a personal best practice:

- Transient hostname: How the network views your system.

- Static hostname: Set by the kernel.

- Pretty hostname: The user-defined hostname.

It is recommended to pick a pretty hostname that is unique and not easily confused with other systems. Allow the transient and static names to be variations on the pretty, and you will be good to go in most circumstances.

Working with hostnames

Now, let’s look at how to view your current hostname. The most basic command used to see this information is hostname -f . This command displays the system’s fully qualified domain name (FQDN). To relate back to the three types of hostnames, this is your transient hostname. A better way, at least in terms of the information provided, is to use the systemd command hostnamectl to view your transient hostname and other system information:

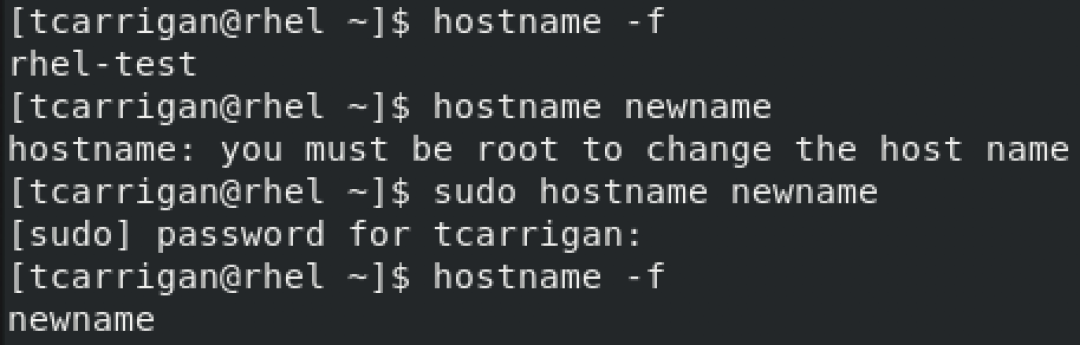

Before moving on from the hostname command, I’ll show you how to use it to change your transient hostname. Using hostname (where x is the new hostname), you can change your network name quickly, but be careful. I once changed the hostname of a customer’s server by accident while trying to view it. That was a small but painful error that I overlooked for several hours. You can see that process below:

It is also possible to use the hostnamectl command to change your hostname. This command, in conjunction with the right flags, can be used to alter all three types of hostnames. As stated previously, for the purposes of this article, our focus is on the transient hostname. The command and its output look something like this:

The final method to look at is the sysctl command. This command allows you to change the kernel parameter for your transient name without having to reboot the system. That method looks something like this:

GNOME tip

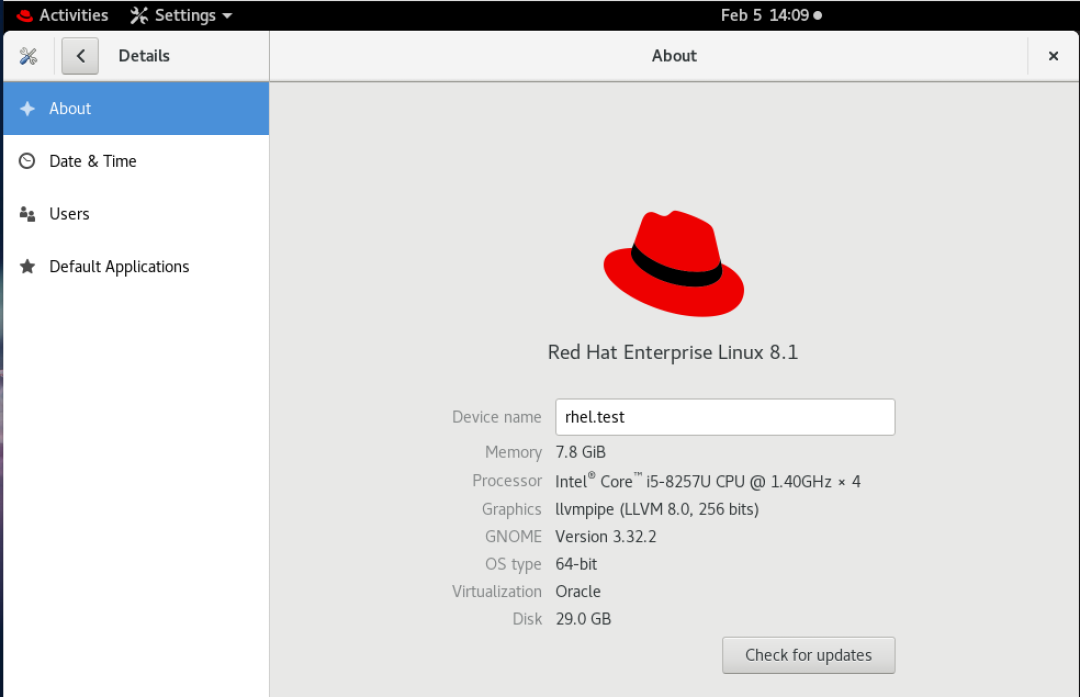

Using GNOME, you can go to Settings -> Details to view and change the static and pretty hostnames. See below:

Wrapping up

I hope that you found this information useful as a quick and easy way to manipulate your machine’s network-visible hostname. Remember to always be careful when changing system hostnames, especially in enterprise environments, and to document changes as they are made.

Want to try out Red Hat Enterprise Linux? Download it now for free.