- What are Pipes in Linux? How does Pipe Redirection Works?

- Pipes in Linux: The general idea

- Keep in mind: Pipe redirects stdout to stdin but not as command argument

- Types of pipes in Linux

- Read the full story

- Pipes and Redirection in Linux

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Standard Input and Output

- 3. Redirecting Into Files

- 3.1. Appending To Files

- 3.2. Redirecting Standard Error

- 3.3. Redirecting into Streams

- 3.4. Redirecting Multiple Streams

- 4. Reading From Files

- 5. Piping Between Applications

- 5.1. Handling Standard Error

- 5.2. Combining Pipes

- 6. Summary

What are Pipes in Linux? How does Pipe Redirection Works?

There are two kinds of pipes in Linux: named and unnamed. Here’s a detailed look at pipe redirection.

You might have used a syntax like cmd0 | cmd1 | cmd2 in your terminal quite too many times.

You probably also know that it is pipe redirection which is used for redirecting output of one command as input to the next command.

But do you know what goes underneath? How pipe redirection actually works?

Not to worry because today I’ll be demystifying Unix pipes so that the next time you go on a date with those fancy vertical bars, you’ll know exactly what’s happening.

Note: I have used the term Unix at places because the concept of pipes (like so many other things in Linux) originates from Unix.

Pipes in Linux: The general idea

Here’s what you’ll be seeing everywhere regarding “what are Unix pipes?”:

- Unix pipes are an IPC (Inter Process Communication) mechanism, that forwards the output of one program to the input of another program.

Now, this is the general explanation that everyone gives. I want to go in deeper. Let’s rephrase the previous line in a more technical way by taking away the abstractions:

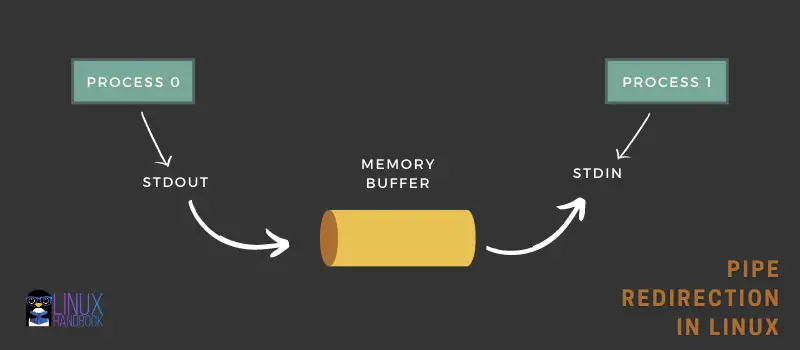

- Unix pipes are an IPC (Inter Process Communication) mechanism that takes the stdout of a program and forwards that to the stdin of another program via a buffer.

Much better. Taking away the abstraction made it much cleaner, and more accurate. You can look at the following diagram to understand how pipe works:

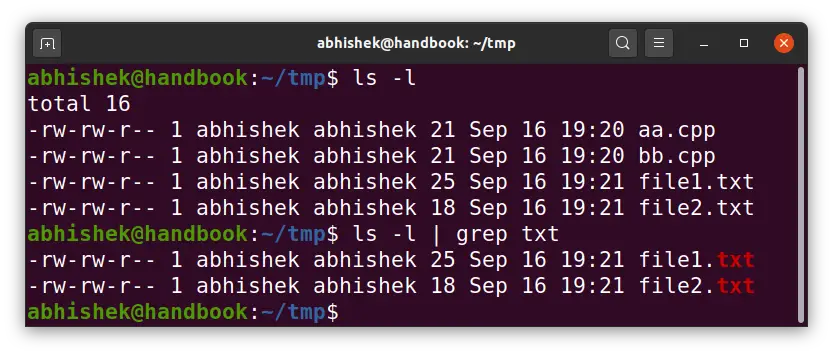

One of the simplest example of the pipe command is to pass some command output to grep command for searching a specific string.

For example, you can search for files with name containing txt like this:

Keep in mind: Pipe redirects stdout to stdin but not as command argument

One very important thing to understand is that pipe transfers the stdout of a command to stdin of another but not as a command argument. I’ll explain it with example.

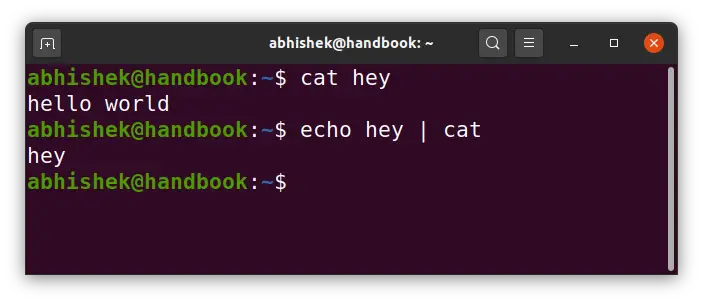

If you use cat command without any arguments, it’ll default to reading from stdin . Here’s an example:

$ cat Subscribe to Linux Handbook for more articles like this ^D Subscribe to Linux Handbook for more articles like this Here I used cat without passing any files, so it defaulted to stdin . Next I wrote a line and then used Ctrl+d to let it know that I’m done writing (Ctrl+d implies EOF or End Of File). Once I was done writing, cat read from stdin , and wrote that very line to stdout .

Now consider the following command:

The second command is NOT equivalent to cat hey . Here, the stdout , «hey», is taken to a buffer, and transferred to the stdin of cat . As there were no command line arguments, cat defaulted to stdin for read, and there was something already in the stdin, so cat command took it, and printed to stdout .

In fact, I created a file named hey and put some content in it. You can see the difference clearly in the image below:

Types of pipes in Linux

There are two kinds of pipes in Linux:

Read the full story

The rest of the article is available to LHB members only. You can sign up now for FREE to read the rest of this article along with access to all members-only posts. You also get subscribed to our fortnightly Linux newsletter.

Pipes and Redirection in Linux

The Kubernetes ecosystem is huge and quite complex, so it’s easy to forget about costs when trying out all of the exciting tools.

To avoid overspending on your Kubernetes cluster, definitely have a look at the free K8s cost monitoring tool from the automation platform CAST AI. You can view your costs in real time, allocate them, calculate burn rates for projects, spot anomalies or spikes, and get insightful reports you can share with your team.

Connect your cluster and start monitoring your K8s costs right away:

1. Introduction

Most shells offer the ability to alter the way that application input and output flows. This can direct output away from the terminal and into files or other applications, or otherwise reading input from files instead of the terminal.

2. Standard Input and Output

Before we understand how redirection works in shells, we first need to understand the standard input and output process.

All applications have three unique streams that connect them to the outside world. These are referred to as Standard Input, or stdin; Standard Output, or stdout; and Standard Error, or stderr.

Standard input is the default mechanism for getting input into an interactive program. This is typically a direct link to the keyboard when running directly in a terminal, and isn’t connected to anything otherwise.

Standard output is the default mechanism for writing output from a program. This is typically a link to the output terminal but is often buffered for performance reasons. This can be especially important when the program is running over a slow network link.

The standard error is an alternative mechanism for writing output from a program. This is typically a different link to the same output terminal but is unbuffered so that we can write errors immediately while the normal output can be written one line at a time .

3. Redirecting Into Files

One common need when we run applications is to direct the output into a file instead of the terminal. Specifically, what we’re doing here is replacing the standard output stream with one that goes where we want: In this case, a file.

This is typically done with the > operator between the application to run and the file to write the output into. For example, we can send the output of the ls command into a file called files as follows:

3.1. Appending To Files

When we use >, then we are writing the output to the file, replacing all of the contents. If needed, we can also append to the file using >> instead:

$ ls -1 *.txt > files $ ls -1 *.text >> files $ ls -1 *.log >> filesWe can use this to build up files using all manner of output if we need to, including just using echo to exact output lines:

$ echo Text Files > files $ ls -1 *.txt >> files $ echo Log Files >> files $ ls -1 *.log >> files3.2. Redirecting Standard Error

On occasion, we need to redirect standard error instead of standard output. This works in the same way, but we need to specify the exact stream.

All three of the standard streams have ID values, as defined in the POSIX specification and used in the C language. Standard input is 0, standard output is 1, and the standard error is 2.

When we use the redirect operators, by default, this applies to standard output. We can explicitly specify the stream to redirect, though, by prefixing it with the stream ID.

For example, to redirect standard error, from the cat command we would use 2>:

We can be consistent and use 1> to redirect standard output if we wish, though this is identical to what we saw earlier.

We can also use &> to redirect both standard output and standard error at the same time:

This sends all output from the command, regardless of which stream it is on, into the same file. This only works in certain shells, though – for example, we can use this in bash or zsh, but not in sh.

3.3. Redirecting into Streams

Sometimes we want to redirect into a stream instead of a file. We can achieve this by using the stream ID, prefixed by &, in place of the filename. For example, we can redirect into standard error by using >&2:

$ echo Standard Output >&1 $ echo Standard Error >&2We can combine this with the above to combine streams, by redirecting from one stream into another. A common construct is to combine standard error into standard output, so that both can be used together. We achieve this using 2>&1 – literally redirecting stream 2 into stream 1:

We can sometimes use this to create new streams, simply by using new IDs. This stream must already have been used elsewhere first though, otherwise, it is an error. Most often this is used as a stream source first.

For example, we can swap standard output and standard error by going via a third stream, using 3>&2 2>&1 1>&3:

This construct doesn’t work correctly in all shells. In bash, the end result is that standard output and standard error are directly swapped. In zsh the result is that both standard output and standard error have ended up on standard output instead.

3.4. Redirecting Multiple Streams

We can easily combine the above to redirect standard output and standard error at the same time. This mostly works exactly as we would expect – we simply combine the two different redirects on the same command:

$ ls -1 > stdout.log 2> stderr.logThis won’t work as desired if we try to redirect both streams into the same file. What happens here is that both streams are redirected individually , and whichever comes second wins, rather than combining both into the same file .

If we want to redirect both into the same file, then we can use &> as we saw above, or else we can use stream combination operators. If we wish to use the stream combination operators, then we must do this after we have redirected into the file, or else only the standard output gets redirected:

4. Reading From Files

Sometimes we also want to achieve the opposite – redirecting a file into an application. We do this using the operator, and the contents of the file will replace the standard input for the application:

When we do this, the only input that the application can receive comes from this source, and it will all happen immediately. It’s effectively the same as when the user types out the entire contents of the file at the very start of the application.

However, the end of the file is signaled to the application as well, which many applications can use to stop processing.

5. Piping Between Applications

The final action that we can perform is to direct the output of one application into another one. This is commonly referred to as piping, and uses the | operator instead:

This directly connects the standard output of our first application into the standard input of the second one and then lets the data directly flow between them.

5.1. Handling Standard Error

The standard error isn’t connected by default, so we’ll still get anything written to that stream appearing in the console. This is by design since the standard error is designed for error reporting and not for normal application output.

If we want to redirect standard error as well then we can use the technique from above to first redirect it into standard output and then pipe into the next application:

$ ls i-dont-exist | wc ls: i-dont-exist: No such file or directory 0 0 0 $ ls i-dont-exist 2>&1 | wc 1 7 44If we want only to pipe standard error then we need to swap the standard output and standard error streams around, as we saw earlier.

$ ls 3>&2 2>&1 1>&3 | wc -l some-file 0 $ ls i-dont-exist 3>&2 2>&1 1>&3 | wc -l 15.2. Combining Pipes

When piping between applications, we can also build arbitrary chains where we are piping between many applications to achieve a result:

$ docker images | cut -d' ' -f1 | tail -n +2 | sort -u | wc -l 17- docker images – Get a list of all Docker images

- cut -d’ ‘ -f1 – Cut this output to only return the first column, where columns are space-separated

- tail -n +2 – Limit this to start from line 2

- sort -u – Sort this list, only returning unique entries

- wc -l – Count the number of lines

So we have a command here to get the number of unique docker images, ignoring the version of the image.

Many console applications are designed for exactly this use, which is why they can often consume input from standard input and write to standard output.

Certain applications also have special modes that allow for this – git, for example, has what is termed porcelain and plumbing commands, where the plumbing commands are specially designed to be combined in this manner while the porcelain commands are designed for human consumption.

6. Summary

Here, we ‘ve seen several techniques for redirecting the input and output of applications either between files or other applications. These are compelling techniques that can give rise to complicated results from simple inputs.

Why not see what else we can do with these?