Переменная PATH в Linux

Когда вы запускаете программу из терминала или скрипта, то обычно пишете только имя файла программы. Однако, ОС Linux спроектирована так, что исполняемые и связанные с ними файлы программ распределяются по различным специализированным каталогам. Например, библиотеки устанавливаются в /lib или /usr/lib, конфигурационные файлы в /etc, а исполняемые файлы в /sbin/, /usr/bin или /bin.

Таких местоположений несколько. Откуда операционная система знает где искать требуемую программу или её компонент? Всё просто — для этого используется переменная PATH. Эта переменная позволяет существенно сократить длину набираемых команд в терминале или в скрипте, освобождая от необходимости каждый раз указывать полные пути к требуемым файлам. В этой статье мы разберёмся зачем нужна переменная PATH Linux, а также как добавить к её значению имена своих пользовательских каталогов.

Переменная PATH в Linux

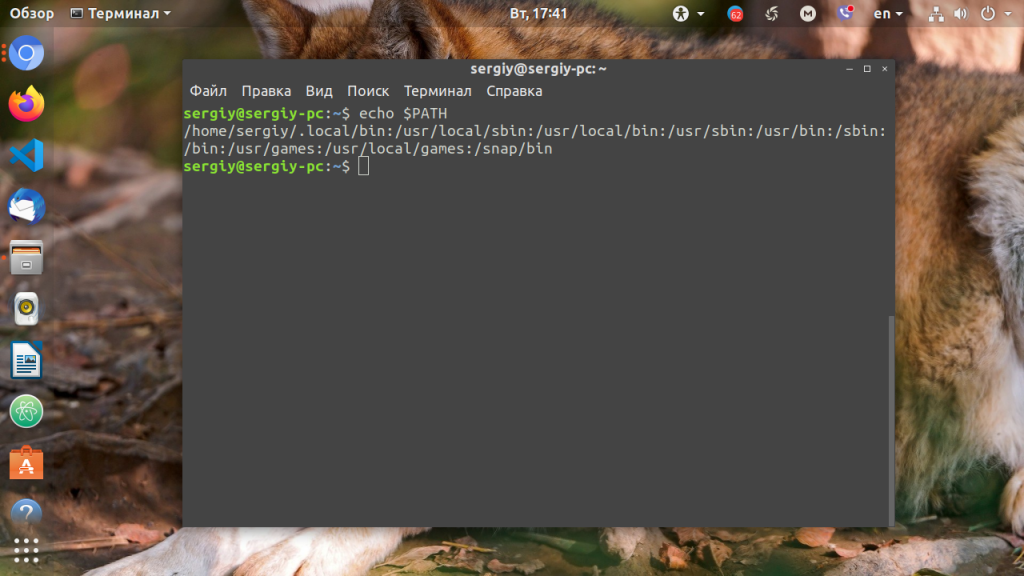

Для того, чтобы посмотреть содержимое переменной PATH в Linux, выполните в терминале команду:

На экране появится перечень папок, разделённых двоеточием. Алгоритм поиска пути к требуемой программе при её запуске довольно прост. Сначала ОС ищет исполняемый файл с заданным именем в текущей папке. Если находит, запускает на выполнение, если нет, проверяет каталоги, перечисленные в переменной PATH, в установленном там порядке. Таким образом, добавив свои папки к содержимому этой переменной, вы добавляете новые места размещения исполняемых и связанных с ними файлов.

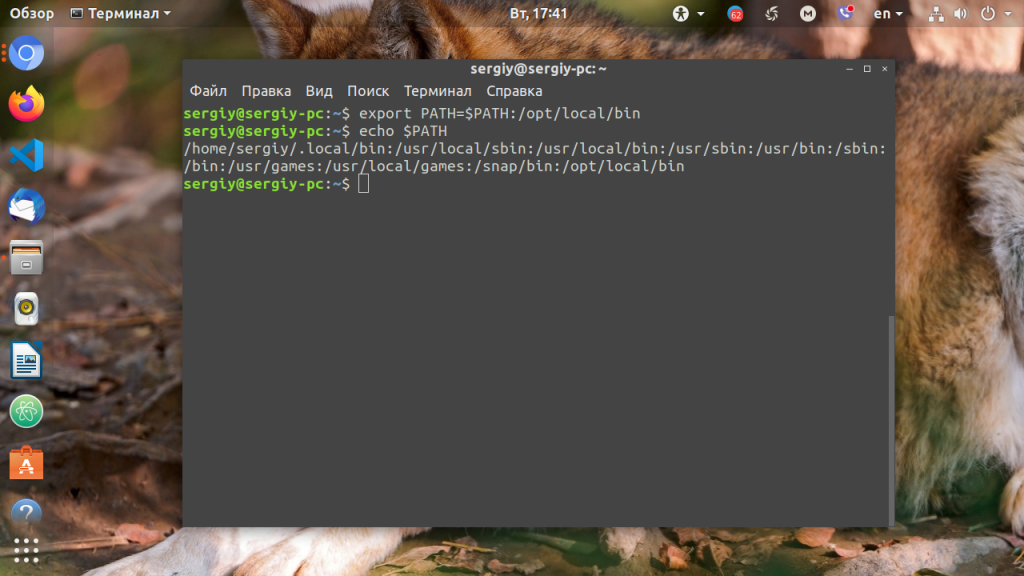

Для того, чтобы добавить новый путь к переменной PATH, можно воспользоваться командой export. Например, давайте добавим к значению переменной PATH папку/opt/local/bin. Для того, чтобы не перезаписать имеющееся значение переменной PATH новым, нужно именно добавить (дописать) это новое значение к уже имеющемуся, не забыв о разделителе-двоеточии:

Теперь мы можем убедиться, что в переменной PATH содержится также и имя этой, добавленной нами, папки:

Вы уже знаете как в Linux добавить имя требуемой папки в переменную PATH, но есть одна проблема — после перезагрузки компьютера или открытия нового сеанса терминала все изменения пропадут, ваша переменная PATH будет иметь то же значение, что и раньше. Для того, чтобы этого не произошло, нужно закрепить новое текущее значение переменной PATH в конфигурационном системном файле.

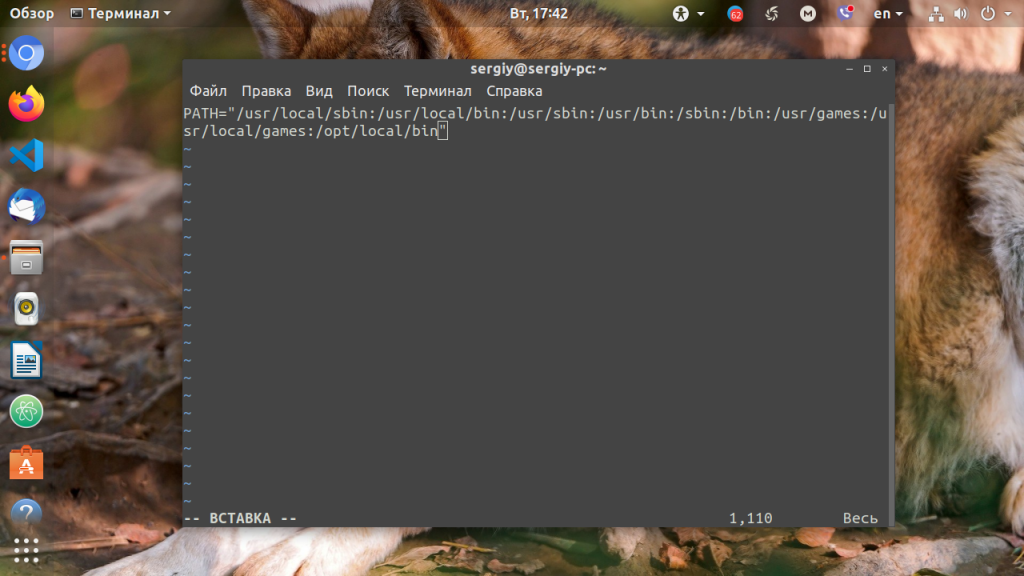

В ОС Ubuntu значение переменной PATH содержится в файле /etc/environment, в некоторых других дистрибутивах её также можно найти и в файле /etc/profile. Вы можете открыть файл /etc/environment и вручную дописать туда нужное значение:

Можно поступить и иначе. Содержимое файла .bashrc выполняется при каждом запуске оболочки Bash. Если добавить в конец файла команду export, то для каждой загружаемой оболочки будет автоматически выполняться добавление имени требуемой папки в переменную PATH, но только для текущего пользователя:

Выводы

В этой статье мы рассмотрели вопрос о том, зачем нужна переменная окружения PATH в Linux и как добавлять к её значению новые пути поиска исполняемых и связанных с ними файлов. Как видите, всё делается достаточно просто. Таким образом вы можете добавить столько папок для поиска и хранения исполняемых файлов, сколько вам требуется.

Обнаружили ошибку в тексте? Сообщите мне об этом. Выделите текст с ошибкой и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

What are the differences between absolute and relative paths?

In computer programming, web development, and Linux system administration, a directory or file path is an important way to identify the location of data on a system.

Programmers often use paths to point to an important coding library, while web developers sometimes point to a graphic or video on the server hosting the site they’re creating, and Linux sysadmins might point to an important configuration file.

A path is like a treasure map describing the layout of a system so that a user or a computer can retrace the steps to retrieve vital data.

[ Keep your most commonly used commands handy with the Linux commands cheat sheet. ]

How to read a path

Great Linux resources

A path describes a location. For instance, /home/tux/example.txt tells you to start at the /home directory on your hard drive and then click into the tux directory, where you’ll find a text file called example.txt .

If it helps, you can say «which contains» between each item in the path as you read it because every item in a path is something «inside» something else. In this example, the statement «start in home, which contains tux, which contains example.txt» is an accurate description of where example.txt is located.

Absolute path

An absolute path makes no assumptions about your current location in relation to the location of the file or directory it’s describing. An absolute path always begins from the absolute start of your hard drive and describes every step you must take through the filesystem to end up at the target location.

For instance, suppose you write a note to your work colleague that says, «Push the button every 108 minutes.» Without telling your colleague where the button is located, these instructions are useless. So you change the instruction to: «Push /usr/share/widgets/button every 108 minutes.»

Now your colleague knows exactly where to locate the button, and the path to the button is the same whether you or your colleague are following the path. From your home directory, the button is located in /usr/share/widgets/button , and from your colleague’s home directory, the button is also located in /usr/share/widgets/button .

The reason is that the path is the same no matter whether the instructions you provide start from the farthest region of the filesystem. You can’t go farther back than / , so once you’re there, you can find usr , which contains share , which contains widgets , which contains the button.

[ Want to test your sysadmin skills? Take a skills assessment today. ]

You can always get the absolute path of a file with the realpath command:

$ cd /usr/share/aclocal $ realpath pkg.m4 /usr/share/aclocal/pkg.m4` $ cd ~ $ realpath example.txt /home/tux/example.txtRelative path

Absolute paths are useful, but they’re not always efficient. If you know where the widgets directory, which contains button , is located. then you don’t necessarily have to go all the way back to / and then usr and then share and so on. Think of it this way: When you stop at a diner on your way to work, you don’t have to go all the way back home to resume your journey to the office. You just step outside the diner and continue on your way, because you know where your office is relative to your current location.

Relative paths use the same principle. Suppose you’re in /var/log/foo and you want to view a file in /var/log/bar . There’s no reason to «travel» all the way back to /var . Instead, use a relative path to look outside of foo and into bar .

Two dots ( .. ) represent moving to a parent directory, so ../bar/file.txt means to move up one directory (into /var/log ) and then descend into /var/log/bar , which contains file.txt .

You may notice that using .. isn’t very descriptive. That’s both the advantage and disadvantage of a relative path. It’s an advantage because it can be quicker to type and it’s flexible. The statement ../bar/file.txt doesn’t care what comes before bar . It only knows that the bar directory contains a file called file.txt . That makes it equally true whether a user keeps the foo and bar directories in /var/log or in /opt or in /home/tux/.var/log or any other location.

Relative paths allow applications and scripts to be largely self-contained. As long as the immediate environment is predictable, you can always reference files from a known location. I often use this trick in Git repositories. I know that no matter where the folder is, the top-level directory is always in a known or discoverable state. Using commands like git rev-parse —show-toplevel allows me to use symlinks and scripts that start at my repository rather than the start of the entire hard drive.

Single dot

It may seem odd at first, but relative paths also make an allowance for making no movement in a path. You may have seen instructions telling you to execute a script like this:

The single dot indicates your current location.

Training & certification

There’s a good reason for this, actually. Whether you know it or not, your computer has several default paths that it assumes you’re referring to every time you run a command. This default location, usually just called «your path» or «your $PATH,» are places your computer looks to find commands you want to run.

Your computer doesn’t inherently know that ls or git are special keyword commands. It executes those applications because when it searches /usr/bin , it finds files called ls and git there. Imagine what would happen if I named a file ls and then set my computer to run the first file it found with that name. Anytime I am in a directory containing an arbitrary file called ls , my computer will attempt to run it. And instead of getting a list of all my files, I’d get whatever ls told the computer to do.

That’s dangerous, so Linux by default doesn’t search arbitrary locations for commands. Instead, you must specify the location of a file you want to run as an application, even when that file is literally right next to you.

Other path notation

I’m using the slash ( / ) symbol because Linux and the internet and many others use a slash as a path separator. While a slash is probably the most common separator, it’s not the only one. Windows systems historically used the backslash ( \ ) as a path separator, although modern Windows systems understand both equally.

Many programming languages use path expressions to describe the inheritance of code libraries. For instance, you might see a Python script referencing time.sleep() or QtWidgets.QVBoxLayout() . In these cases, dot separators indicate a kind of path. The time module contains the sleep function, and the QtWidgets module contains the QVBoxLayout function. You may not interact with these paths in the same way, but they are communicating the same concept. They are mapping a resource’s location and ensuring that a programmer or a program can locate that resource reliably.

In fact, when an application fails to run on a computer, it’s often due to a missing library. That means that the computer followed a path and found that there was no library in the place described. The fix is often installing the missing dependency, which places the required library in the expected path.

Using paths

A path is a map, and like a treasure map, a file path can be intended for you (the person who buried the treasure in the first place) or for someone else (someone you want to share the treasure with). Unlike a treasure map pointing to a single buried treasure, a file path can point to data that exists on lots of people’s computers. Be mindful of how you describe the location of an important resource, and when possible use installers like Autotools or CMake to ensure that your scripts and applications can adapt to different installation preferences.

If you’re still coming to grips with paths, remember that practice makes perfect. The more you use a terminal for navigation around your system, the quicker filesystem paths feel natural.