- Getting Started with Python Programming and Scripting in Linux – Part 1

- Install Python on Linux

- Install Python IDLE on Linux

- Do Basic Operations with Python on Linux

- A Brief Comment About Object-Oriented Programming

- Illustrating Methods and Properties of Objects: Lists in Python

- 2. Using Python on Unix platforms¶

- 2.1. Getting and installing the latest version of Python¶

- 2.1.1. On Linux¶

- 2.1.2. On FreeBSD and OpenBSD¶

- 2.1.3. On OpenSolaris¶

- 2.2. Building Python¶

- 2.3. Python-related paths and files¶

- 2.4. Miscellaneous¶

- 2.5. Custom OpenSSL¶

Getting Started with Python Programming and Scripting in Linux – Part 1

It has been said (and often required by recruitment agencies) that system administrators need to be proficient in a scripting language. While most of us may be comfortable using Bash (or other Linux shells of our choice) to run command-line scripts, a powerful language such as Python can add several benefits.

To begin with, Python allows us to access the tools of the command-line environment and to make use of Object Oriented Programming features (more on this later in this article).

On top of it, learning Python can boost your career in the fields of creating desktop applications and learning data science.

Being so easy to learn, so vastly used, and having a plethora of ready-to-use modules (external files that contain Python statements), no wonder Python is the preferred language to teach programming to first-year computer science students in the United States.

In this 2-article series, we will review the fundamentals of Python in hopes that you will find it useful as a springboard to get you started with programming and as a quick reference guide afterward.

That said, let’s get started.

Install Python on Linux

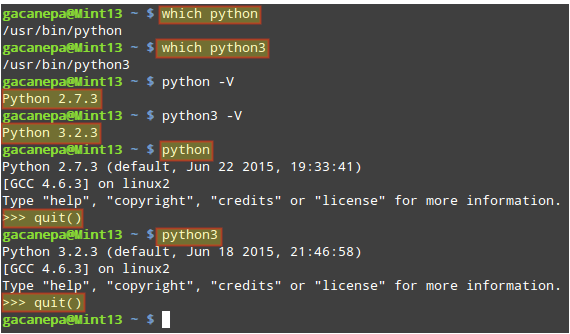

Python versions 2.x and 3.x are usually available in most modern Linux distributions out of the box. You can enter a Python shell by typing python or python3 in your terminal emulator and exit with quit() :

$ which python $ which python3 $ python -v $ python3 -v $ python >>> quit() $ python3 >>> quit()

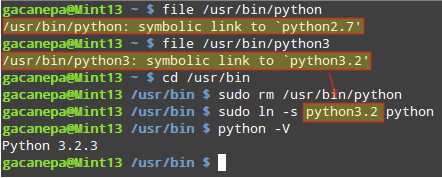

If you want to discard Python 2.x and use 3.x instead when you type python, you can modify the corresponding symbolic links as follows:

$ sudo rm /usr/bin/python $ cd /usr/bin $ ln -s python3.2 python # Choose the Python 3.x binary here

By the way, it is important to note that although versions 2.x are still used, they are not actively maintained. For that reason, you may want to consider switching to 3.x as indicated above. Since there are some syntax differences between 2.x and 3.x, we will focus on the latter in this series.

To install Python 3.x on your respective Linux distributions, run:

$ sudo apt install python3 [On Debian, Ubuntu and Mint] $ sudo yum install python3 [On RHEL/CentOS/Fedora and Rocky/AlmaLinux] $ sudo emerge -a dev-lang/python [On Gentoo Linux] $ sudo apk add python3 [On Alpine Linux] $ sudo pacman -S python3 [On Arch Linux] $ sudo zypper install python3 [On OpenSUSE]

Install Python IDLE on Linux

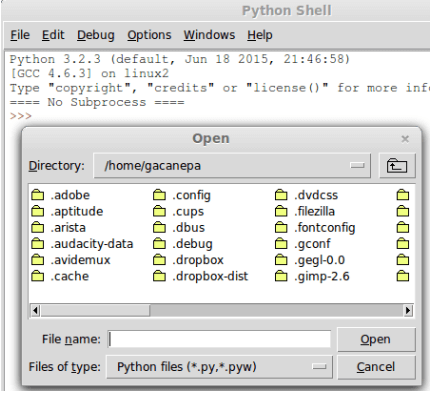

Another way you can use Python in Linux is through the IDLE (the Python Integrated Development Environment), a graphical user interface for writing Python code.

$ sudo apt install idle [On Debian, Ubuntu and Mint] $ sudo yum install idle [On RHEL/CentOS/Fedora and Rocky/AlmaLinux] $ sudo apk add idle [On Alpine Linux] $ sudo pacman -S idle [On Arch Linux] $ sudo zypper install idle [On OpenSUSE]

Once installed, you will see the following screen after launching the IDLE. While it resembles the Python shell, you can do more with the IDLE than with the shell.

1. open external files easily (File → Open).

2) copy (Ctrl + C) and paste (Ctrl + V) text, 3) find and replace text, 4) show possible completions (a feature known as Intellisense or Autocompletion in other IDEs), 5) change the font type and size, and much more.

On top of this, you can use IDLE to create desktop applications.

Since we will not be developing a desktop application in this 2-article series, feel free to choose between the IDLE and the Python shell to follow the examples.

Do Basic Operations with Python on Linux

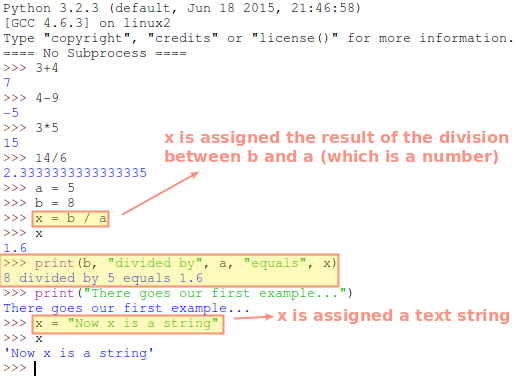

As is to be expected, you can perform arithmetic operations (feel free to use as many parentheses as needed to perform all the operations you want!) and manipulate text strings very easily with Python.

You can also assign the results of operations to variables and display them on the screen. A handy feature in Python is concatenation – just supply the values of variables and/or strings in a comma-delimited list (inside parentheses) to the print function and it will return the sentence composed by the items in the sequence:

>>> a = 5 >>> b = 8 >>> x = b / a >>> x 1.6 >>> print(b, "divided by", a, "equals", x)

Note that you can mix variables of different types (numbers, strings, booleans, etc) and once you have assigned a value to a variable you can change the data type without problems later (for this reason Python is said to be a dynamically typed language).

If you attempt to do this in a statically typed language (such as Java or C#), an error will be thrown.

A Brief Comment About Object-Oriented Programming

In Object Oriented Programming (OOP), all entities in a program are represented as objects and thus they can interact with others. As such, they have properties and most of them can perform actions (known as methods).

For example, let’s suppose we want to create a dog object. Some of the possible properties are color, breed, age, etc, whereas some of the actions a dog can perform are bark(), eat(), sleep(), and many others.

Methods names, as you can see, are followed by a set of parentheses which may (or may not) contain one (or more) arguments (values that are passed to the method).

Let’s illustrate these concepts with one of the basic object types in Python: lists.

Illustrating Methods and Properties of Objects: Lists in Python

A list is an ordered group of items, which do not necessarily have to be all of the same data types. To create an empty list named rockBands, use a pair of square brackets as follows:

To append an item to the end of the list, pass the item to the append() method as follows:

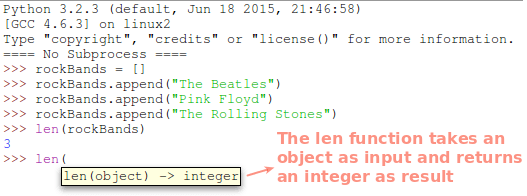

>>> rockBands = [] >>> rockBands.append("The Beatles") >>> rockBands.append("Pink Floyd") >>> rockBands.append("The Rolling Stones") To remove an item from the list, we can pass the specific element to the remove() method, or the position of the element (count starts at zero) in the list to pop() .

In other words, we can use either of the following options to remove “The Beatles” from the list:

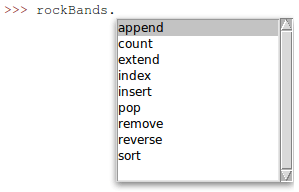

>>> rockBands.remove("The Beatles") or >>> rockBands.pop(0) You can display the list of available methods for an object by pressing Ctrl + Space once you’ve typed the name followed by a dot:

A property of a list object is the number of items it contains. It is actually called length and is invoked by passing the list as an argument to the len built-in function (by the way, the print statement, which we exemplified earlier-, is another Python built-in function).

If you type len followed by opening parentheses in the IDLE, you will see the default syntax of the function:

Now, what about the individual items on the list? Do they have methods and properties as well? The answer is yes. For example, you can convert a string item to uppercase and get the number of characters it contains as follows:

>>> rockBands[0].upper() 'THE BEATLES' >>> len(rockBands[0]) 11

Summary

In this article, we have provided a brief introduction to Python, its command-line shell, and the IDLE, and demonstrated how to perform arithmetic calculations, how to store values in variables, how to print back those values to the screen (either on its own or as part of a concatenation), and explained through a practical example what are the methods and properties of an object.

In the next article, we will discuss control flow with conditionals and loops. We will also demonstrate how to use what we have learned to write a script to help us in our sysadmin tasks.

Does Python sound like something you would like to learn more about? Stay tuned for the second part in this series (where among other things we will combine the bounties of Python and command-line tools in a script), and also consider buying the best udemy python courses to upgrade your knowledge.

As always, you can count on us if you have any questions about this article. Just send us a message using the contact form below and we will get back to you as soon as possible.

2. Using Python on Unix platforms¶

2.1. Getting and installing the latest version of Python¶

2.1.1. On Linux¶

Python comes preinstalled on most Linux distributions, and is available as a package on all others. However there are certain features you might want to use that are not available on your distro’s package. You can easily compile the latest version of Python from source.

In the event that Python doesn’t come preinstalled and isn’t in the repositories as well, you can easily make packages for your own distro. Have a look at the following links:

2.1.2. On FreeBSD and OpenBSD¶

pkg_add -r python pkg_add ftp://ftp.openbsd.org/pub/OpenBSD/4.2/packages//python-.tgz

pkg_add ftp://ftp.openbsd.org/pub/OpenBSD/4.2/packages/i386/python-2.5.1p2.tgz

2.1.3. On OpenSolaris¶

You can get Python from OpenCSW. Various versions of Python are available and can be installed with e.g. pkgutil -i python27 .

2.2. Building Python¶

If you want to compile CPython yourself, first thing you should do is get the source. You can download either the latest release’s source or just grab a fresh clone. (If you want to contribute patches, you will need a clone.)

The build process consists of the usual commands:

./configure make make install

Configuration options and caveats for specific Unix platforms are extensively documented in the README.rst file in the root of the Python source tree.

make install can overwrite or masquerade the python3 binary. make altinstall is therefore recommended instead of make install since it only installs exec_prefix /bin/python version .

2.3. Python-related paths and files¶

These are subject to difference depending on local installation conventions; prefix and exec_prefix are installation-dependent and should be interpreted as for GNU software; they may be the same.

For example, on most Linux systems, the default for both is /usr .

Recommended location of the interpreter.

prefix /lib/python version , exec_prefix /lib/python version

Recommended locations of the directories containing the standard modules.

prefix /include/python version , exec_prefix /include/python version

Recommended locations of the directories containing the include files needed for developing Python extensions and embedding the interpreter.

2.4. Miscellaneous¶

To easily use Python scripts on Unix, you need to make them executable, e.g. with

and put an appropriate Shebang line at the top of the script. A good choice is usually

which searches for the Python interpreter in the whole PATH . However, some Unices may not have the env command, so you may need to hardcode /usr/bin/python3 as the interpreter path.

To use shell commands in your Python scripts, look at the subprocess module.

2.5. Custom OpenSSL¶

- To use your vendor’s OpenSSL configuration and system trust store, locate the directory with openssl.cnf file or symlink in /etc . On most distribution the file is either in /etc/ssl or /etc/pki/tls . The directory should also contain a cert.pem file and/or a certs directory.

$ find /etc/ -name openssl.cnf -printf "%h\n" /etc/ssl

$ curl -O https://www.openssl.org/source/openssl-VERSION.tar.gz $ tar xzf openssl-VERSION $ pushd openssl-VERSION $ ./config \ --prefix=/usr/local/custom-openssl \ --libdir=lib \ --openssldir=/etc/ssl $ make -j1 depend $ make -j8 $ make install_sw $ popd

$ pushd python-3.x.x $ ./configure -C \ --with-openssl=/usr/local/custom-openssl \ --with-openssl-rpath=auto \ --prefix=/usr/local/python-3.x.x $ make -j8 $ make altinstall

Patch releases of OpenSSL have a backwards compatible ABI. You don’t need to recompile Python to update OpenSSL. It’s sufficient to replace the custom OpenSSL installation with a newer version.