- What are character special and block special files in a unix system? [duplicate]

- 3 Answers 3

- Special file

- Block special files

- Character special files

- Linux file types

- How can I tell if a file is special?

- Test for block special

- Test for character special

- Using stat

- What are character special and block special files in a unix system?

- Solution 2

- Solution 3

What are character special and block special files in a unix system? [duplicate]

How are character special files and block special files different from regular files in a Unix-like system? Why are they called “character special” and “block special” respectively?

3 Answers 3

When a program reads or writes data from a file, the requests go to a kernel driver. If the file is a regular file, the data is handled by a filesystem driver and it is typically stored in zones on a disk or other storage media, and the data that is read from a file is what was previously written in that place. There are other file types for which different things happen.

When data is read or written to a device file, the request is handled by the driver for that device. Each device file has an associated number which identifies the driver to use. What the device does with the data is its own business.

Block devices (also called block special files) usually behave a lot like ordinary files: they are an array of bytes, and the value that is read at a given location is the value that was last written there. Data from block device can be cached in memory and read back from cache; writes can be buffered. Block devices are normally seekable (i.e. there is a notion of position inside the file which the application can change). The name “block device” comes from the fact that the corresponding hardware typically reads and writes a whole block at a time (e.g. a sector on a hard disk).

Character devices (also called character special files) behave like pipes, serial ports, etc. Writing or reading to them is an immediate action. What the driver does with the data is its own business. Writing a byte to a character device might cause it to be displayed on screen, output on a serial port, converted into a sound, . Reading a byte from a device might cause the serial port to wait for input, might return a random byte ( /dev/urandom ), . The name “character device” comes from the fact that each character is handled individually.

Special file

In a computer operating system, a special file is a type of file stored in a file system. A special file is sometimes also called a device file.

The purpose of a special file is to expose the device as a file in the file system. A special file provides a universal interface for hardware devices (and virtual devices created and used by the kernel), because tools for file I/O can access the device.

When data is red from or written to a special file, the operation happens immediately, and is not subject to conventional filesystem rules.

In Linux, there are two types of special files: block special file and character special file.

Block special files

A block special file acts as a direct interface to a block device. A block device is any device which performs data I/O in units of blocks.

Examples of block special files:

- /dev/sdxn — mountedpartitions of physicalstorage devices. The letter x refers to a physical device, and the number n refers to a partition on that device. For instance, /dev/sda1 is the first partition on the first physical storage device.

- /dev/loopn — loop devices. These are special devices which allow a file in the filesystem to be used as a block device. The file may contain an entire filesystem of its own, and be accessed as if it were a mounted partition on a physical storage device. For example, an ISO disk image file may be mounted as a loop device.

To know how big a block is on your system, run «blockdev —getbsz device» as root, e.g.:

sudo blockdev --getbsz /dev/sda1

In this example, the block size is 4096 bytes (4 kibibytes).

Character special files

A character special file is similar to a block device, but data is written one character (eight bits, or one byte) at a time.

Examples of character special files:

- /dev/stdin (Standard input.)

- /dev/stdout (Standard output.)

- /dev/stderr (Standard error.)

- /dev/random (PRNG which may delay returning a value to acquire additional entropy.)

- /dev/urandom (PRNG which always returns a value immediately, regardless of required entropy.)

- /dev/null (The null device. Reading from this file always gets a null byte; writing to this file successfully does nothing.)

Linux file types

In the Linux kernel, file types are declared in the header file sys/stat.h. The type name, symbolic name, and bitmask for each Linux file type is listed below.

| Type name | Symbolic name | Bitmask |

|---|---|---|

| Socket | S_IFSOCK | 0140000 |

| Symbolic link | S_IFLNK | 0120000 |

| Regular file | S_IFREG | 0100000 |

| Block special file | S_IFBLK | 0060000 |

| Directory | S_IFDIR | 0040000 |

| Character special file | S_IFCHR | 0020000 |

| FIFO (named pipe) | S_IFIFO | 0010000 |

How can I tell if a file is special?

Test for block special

In bash, the command «test -b file» returns an exit status of 0 if file is block special, or 1 if file is another type or does not exist.

test -b /dev/null; echo $? # character special files are not block special

Test for character special

To determine if a file is character special, use «test -c file«:

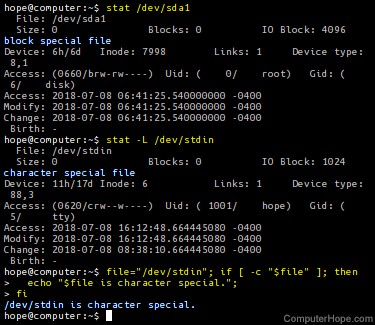

Using stat

You can also check a file’s type with stat:

File: /dev/sda1 Size: 0 Blocks: 0 IO Block: 4096 block special file Device: 6h/6d Inode: 7998 Links: 1 Device type: 8,1 Access: (0660/brw-rw----) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 6/ disk) Access: 2018-07-08 06:41:25.540000000 -0400 Modify: 2018-07-08 06:41:25.540000000 -0400 Change: 2018-07-08 06:41:25.540000000 -0400 Birth: -

File: /dev/random Size: 0 Blocks: 0 IO Block: 4096 character special file Device: 6h/6d Inode: 6518 Links: 1 Device type: 1,8 Access: (0666/crw-rw-rw-) Uid: ( 0/ root) Gid: ( 0/ root) Access: 2018-07-08 06:41:19.676000000 -0400 Modify: 2018-07-08 06:41:19.676000000 -0400 Change: 2018-07-08 06:41:19.676000000 -0400 Birth: -

What are character special and block special files in a unix system?

When a program reads or writes data from a file, the requests go to a kernel driver. If the file is a regular file, the data is handled by a filesystem driver and it is typically stored in zones on a disk or other storage media, and the data that is read from a file is what was previously written in that place. There are other file types for which different things happen.

When data is read or written to a device file, the request is handled by the driver for that device. Each device file has an associated number which identifies the driver to use. What the device does with the data is its own business.

Block devices (also called block special files) usually behave a lot like ordinary files: they are an array of bytes, and the value that is read at a given location is the value that was last written there. Data from block device can be cached in memory and read back from cache; writes can be buffered. Block devices are normally seekable (i.e. there is a notion of position inside the file which the application can change). The name “block device” comes from the fact that the corresponding hardware typically reads and writes a whole block at a time (e.g. a sector on a hard disk).

Character devices (also called character special files) behave like pipes, serial ports, etc. Writing or reading to them is an immediate action. What the driver does with the data is its own business. Writing a byte to a character device might cause it to be displayed on screen, output on a serial port, converted into a sound, . Reading a byte from a device might cause the serial port to wait for input, might return a random byte ( /dev/urandom ), . The name “character device” comes from the fact that each character is handled individually.

Solution 2

They point to a driver and can be created by mknod . Looking at its man page, it seems that block devices are buffered while character devices are unbuffered. Block devices have a «block size» that indicate the size of the blocks that are accessible. (for storage devices, the block size is typically between 512 B and 4 KiB) Storage devices and memory are typically accessed as block devices, while devices such as serial ports and terminals are typically accessed as character devices.

They are typically found in /dev (and can not function on partitions mounted with a nodev option (or its equivalent))

In ls -l show two comma-separated numbers for devices in the place where the size is normally found. Those are the major and minor numbers, that point to the driver. Their type are also indicated as «c» or «b» in the permission column of the ls -l output.

/dev can be populated in several ways. On recent Linux kernel versions udev is typically used, on Solaris it contains links to /devices , which is a virual devfs filesystem.

Solution 3

File Types in Unix/Linux: Ordinary or Regular Files, Directories, Device (Special) Files, Links, Named Pipes, and Sockets.

A device (special) file is an interface for a device driver that appears in a file system as if it were an ordinary file. They are Character devices, Block devices and Pseudo-devices (like /dev/null ).

Character-driven will send one character at the time, thus you need a small load to carry, but have to make many requests. Block-driven means you get a large collection of characters (data) so you have a** bigger load but have to do less requests. Analogy: Basically the same as buying soda by the bottle, or by the crate.

Block-driven is useful when you know how much data you can expect, which is often the case with files on disk.

Character-driven is more practical when you don’t know when your data will stop thus you keep it running until no more characters get through. For example, an Internet connection, as you don’t know the size of the data stream that you will receive from the server.

For example:

- Character device drivers are special files allowing the OS to communicate with input/output devices. Examples: Keyboard, Mouse, Monitor, audio or graphics cards and Braille.

- Block devices are for communicating with storage devices and capable of buffering output and storing data for later retrieval. Examples: Hard drive, memory.