Find out what device /dev/root represents in Linux?

On linux, there is a /dev/root device node. This will be the same block device as another device node, like /dev/sdaX . How can I resolve /dev/root to the ‘real’ device node in this situation, so that I can show a user a sensible device name? For example, I might encounter this situation when parsing /proc/mounts . I’m looking for solutions that would work from a shell/python script but not C.

have you checked here ? linux-diag.sourceforge.net/Sysfsutils.html It recommends way to query the kernel about attached devices of all kinds, not sure, if its what you are looking for !

6 Answers 6

Parse the root= parameter from /proc/cmdline .

This works on the three distros (fc14, rhel5, ubuntu 11.04) that I’ve looked at, with the slight caveat that there is an extra step needed to deal with root=UUID= type arguments.

readlink does not always work, I’m working on this problem right now and found a user whose system shows no results from: readlink /dev/root — which tripped a glitch in the program I’m working on, which is why I came to this thread. The correct test is to first do: readlink /dev/root, then if null, find it in /proc/cmdline, but parsing /proc/cmdline is not as easy as a better solution, so I’ll keep looking.

On the systems I’ve looked at, /dev/root is a symlink to the real device, so readlink /dev/root (or readlink -f /dev/root if you want the full path), will do it.

Just to clarify, some systems with /dev/root will NOT show output for either ls -l or readlink because it’s not a link, not in the normal sense we think of links anyway. I’m hitting this issue right now. So I’d update this answer to be correct for the systems he’s looked at, but incorrect for an entire class of systems, like current ubuntu I believe, that he had not seen. I also had not seen this new variant for what it’s worth until recently.

This should probably be updated, because a lot of the information given here is misleading, and may actually never have been comprehensively correct.

For the / mount point, you are just told that it corresponds to /dev/root, which is not the real device you are looking for.

Of course, you can look at the kernel command line and see on which initial root filesystem Linux was instructed to boot (root parameter):

$ cat /proc/cmdline mem=512M console=ttyS2,115200n8 root=/dev/mmcblk0p2 rw rootwait

However, this doesn’t mean that what you see is the current root device. Many Linux systems boot on intermediate root filesystems (like initramdisks and initramfs), which are just used to access the final one.

One thing this points out was that the thing in /proc/cmdline is not necessarily the actual final device root actually live on.

That’s from the busybox people, who I assume know what they are talking about when it comes to boot situations.

The second useful resource I found is a very old Slackware thread about the question of /dev/root, from the age of this thread, we can see that all the variants were always present, but I believe ‘most’ distros were using the symbolic link method, but that was a simple kernel compile switch, it could make one, or not make one if I understood the posters correctly, that is, switch it one way, and readlink /dev/root reports the real device name, switch it the other, and it doesn’t.

Since the main topic of that thread was how to get rid of /dev/root, they had to get into what it actually is, what makes it, etc, which means, they had to understand it to get rid of it.

gnashly explained it well:

/dev/root is a generic device which can be used in the fstab. One can also use ‘rootfs’. Doing this offers some advantage in that it allows yout to be less specific. What I mean is, if the root partition is on an external drive, it may not always show up as the same device and successfully mounting it as / would require changing the fstab to match the correct device. By using /dev/root it will always match whatever device is specified in the kernel boot paramters from lilo or grub.

/dev/root has always been present as a virtual mount point, even if you never saw it. So has rootfs (compare this to the special virtual devices like proc and tmpfs which have no preceeding /dev)

/dev/root is a virtual device like ‘proc’ or /dev/tcp’. There is no device node in /dev for these things -it’s already in the kernel as a virtual device.

This explains why a symbolic link does not necessarily exist. I’m surprised I never hit this issue before now, given that I maintain some programs that need to know this information, but better late than never.

I believe some of the solutions offered here will ‘often’ work, and are probably what I will do, but they are not the actual true solution to the problem, which as the busybox author noted, is significantly more complicated to implement in a very robust manner.

[UPDATE:> After getting some user test data, I’m going with the mount method, which seemed to be ok for some cases at least. The /proc/cmdline was not useful because there are too many variants. In the first example, you see the old method. This is less and less common because it’s strongly discouraged to use it (the original /dev/sdx6 type syntax) because those paths can change dynamically (swap disk order, insert new disk, etc, and suddenly /dev/sda1 becomes /dev/sdb1).

root=/dev/sda1 root=UUID=5a25cf4a-9772-40cd-b527-62848d4bdfda root=LABEL=random string root=PARTUUID=a2079bfb-02 VS the very clean and easy to parse:

mount /dev/sda1 on / type ext4 (rw,noatime,data=ordered) In the case of cmdline, you’ll see, the only variant that is the right ‘answer’ in theory is the first, deprecated one, since you should not refer root to a moving target like /dev/sdxy

The next two require doing the further action of getting the symbolic link from that string in either /dev/disk/by-uuid or /dev/disk/by-label

The last one requires I believe using parted -l to find what that parted id is pointing to.

That’s only the variants I know of and have seen, there could well be others, like GPTID, for example.

So the solution I’m using is this:

first, see if /dev/root is a symbolic link. If it is, verify it’s not to /dev/disk/by-uuid or by-label, if it is, you have to do a second step of processing to get the last real path. Depends on the tool you use.

If you got nothing, then go to mount, and see how that is. As a last fallback case, one I’m not using because the arguments given against it not even necessarily being the actual partition or device in question are good enough for me to reject that solution for my program. mount is not a fully robust solution, and I’m sure given enough samples, it would be easy to find cases where it’s not right at all, but I believe these two cases cover ‘most’ users, which is all I needed.

The nicest, cleanest, and most reliable solution would have been for the kernel to just always make the symbolic link, which would not have hurt anything or anyone, and call it good, but that’s not how it worked out in the real world. .

I don’t consider any of these as ‘good or robust’ solutions, but the mount option appears to satisfy the ‘good enough’, and if the truly robust solution is required, use the stuff that busybox recommended.

Who Is Root? Why Does Root Exist?

Have you ever wondered why there is a special account named root in Linux? Do you know what are the recommended best practices to use this account? Are you aware of the scenarios where it must be used and those where it doesn’t? If you answered “yes” to one or more of these questions, keep reading.

In this post we will provide a reference with information about the root account that you will want to keep handy.

What is root?

To begin, let us keep in mind that the hierarchy of directories in Unix-like operating systems has been designed as a tree-like structure. The starting point is a special directory represented by a forward slash (/) with all other directories initially branching off from it. Since this is analogous to an actual tree, / is called the root directory.

In the following image we can see the output of:

which illustrates the analogy between / and the root of a tree.

Although the reasons behind the naming of the root account are not quite clear, it is likely due to the fact that root is the only account having write permissions inside / .

Additionally, root has access to all files and commands in any Unix-like operating system and it is often referred to as the superuser for that reason.

On a side note, the root directory (/) must not be confused with /root , which is the home directory of the root user. In fact, /root is a subdirectory of / .

Gaining Access to root Permissions

When we talk about root (or superuser) privileges, we refer to the permissions that such account has on the system. These privileges include (but are not limited to) the ability to modify the system and to grant other users certain access permissions to its resources.

The reckless use of this power can lead to system corruption at best and total failure at worst. That is why the following guidelines are accepted as best practices when it comes to accessing the privileges of the root account:

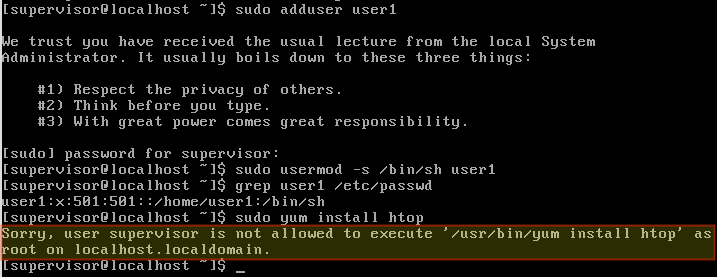

Initially, use the root account to run visudo. Use that command to edit /etc/sudoers to grant the minimum superuser privileges that a given account (e.g. supervisor) needs.

Moving forward, login as supervisor and use sudo to perform user management tasks. You will notice that attempting to perform other tasks that require superuser permissions (removing packages, for example) should fail.

Repeat the above two steps whenever needed, and once done, use the exit command to return to your unprivileged account immediately.

At this point you should ask yourself, Are the any other tasks that pop up on a periodic basis that need superuser privileges? If so, grant the necessary permissions in /etc/sudoers either for a given account or group, and continue avoiding the use of the root account at the extent possible.

Summary

This post can serve as a reference for the proper use of the root account in a Unix-like operating system. Feel free to add it to your bookmarks and return as many times as you want!

As always, drop us a note using the comment form below if you have any questions or suggestions about this article. We look forward to hearing from you!

What is Root Account in Linux

The root account, or root user, has the highest privilege over the system, having complete control over it.

They can easily install any program with the highest privilege, create a user account, assign permissions, and give different privileges to users’ accounts.

Short History

The root account is created by the system administrator who sets up the system or server.

The default user ID for the root user in most Linux distributions is 0.

How do I become a Root User on Linux?

To log into the system as the root user, you need to use “root” as the username and the password that the system administrator used while setting up the system or server.

However, it is not recommended to directly access a Linux system with a root user; instead, create a normal account and add him to the sudo group.

What is the Sudo Group?

The sudo group exists in most Linux systems and holds root level privileges. If you add your normal user to this group, you will have access to those root level privileges.

Only the root user or a user with sudo access can add a normal user to the sudo group.

Once the normal user is added to the sudo group, they can easily execute any command with the highest privileges by adding sudo in front of each command.

$ sudo apt updateAfter that, they will require the current user’s password to execute the command.

$ sudo apt update [sudo] password for linuxtldr: Back to the Root User

Having access to the system as the root user lets some applications or packages act smartly (referring to malware) to get system access without user awareness.

In those cases, it is recommended to create an application profile by using a program like SELinux or AppArmor for Red Hat or Ubuntu.

That’s all for now. If you have any suggestions for adding more to this article, do let us know in the comment section.